Great Nicobar’s great betrayal

Pankaj SekhsariaFebruary 19, 2023 | Reflections

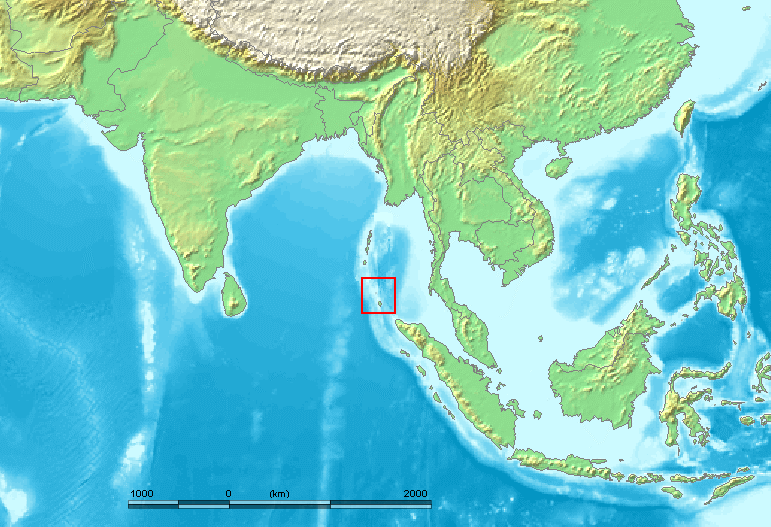

In a set of developments that have unfolded with uncharacteristic speed over the last two years, India’s Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has cleared the decks for a mega-infrastructure project in Great Nicobar Island situated at the southern tip of the Andaman and Nicobar Island group in the Bay of Bengal. As this plan begins to develop hastily, a special issue of Frontline looks at why this biosphere reserve should be left alone. This Backchannels post provides an overview of the various reasons outlined in that special issue.

Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal [Image courtesy: edited by M.Minderhoud, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

In the opening article of this special issue, Pankaj Sekhsaria details why this proposed infrastructure project in Great Nicobar Island is a “mega folly”. The centre-piece of the plan euphemistically labelled the ‘Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island’ is a Rs. 35,000 crore trans-shipment port, an international airport, a power plant and a greenfield township spread over more than 130 sq km of pristine forest. The ecologically rich island is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. The project seeks to increase the population of the island from the current 8000 people to 3,50,000 (a 4000% increase) over the next 30 years. It also envisages the cutting of nearly a million trees in a largely pristine and untouched rain-forest ecosystem.

Flawed environmental clearance

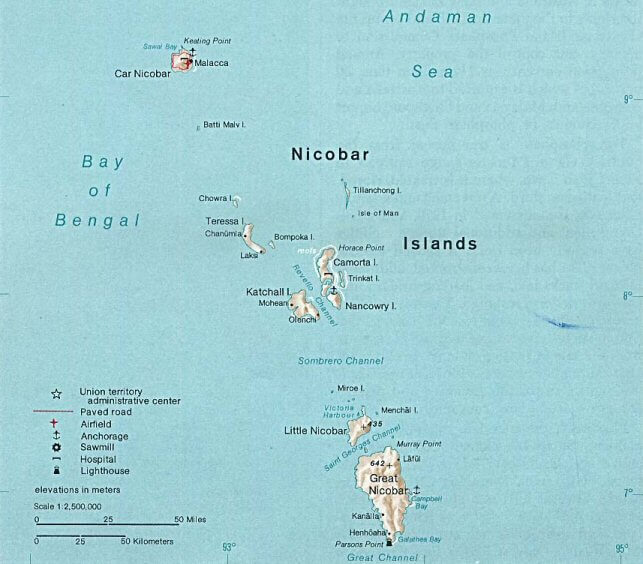

The Nicobar Islands [Image Courtesy: Taken from Perry-Castañeda Library (PCL), originally from CIA Indian Ocean Atlas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

The process started in September 2020 with India’s top planning agency, the NITI Aayog issuing a request for proposals (RfP) for a master plan for the project and the subsequent release in March 2021 of a 126 page pre-feasibility report (PFR) by international consultant AECOM India Pvt Ltd. Hyderabad based Vimta Labs was contracted to prepare the environment impact assessment (EIA) report, the draft of which was released in December 2021, marking the completion of the first formal stage of the process. This period was also marked with hectic activity aimed at easing out the clearance processes. First in January 2021, the Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary was de-notified to free it as the port site. This in spite of the fact that the beach here is among the most important nesting sites in the northern Indian Ocean of the Giant leatherback turtle, the world’s largest marine turtle, as explained by Shrishtee Bajpai, in the article “Should the leatherback turtle go to court?”.

Ishika Ramakrishna discusses in the next article the ecological richness of island and the huge loss that will be experienced if the project is allowed to go through. The draft EIA report, for instance, had many problems and researchers and NGOs from across the country raised nearly 400 concerns related to ecology, rights of the indigenous communities and the tectonic volatility and disaster vulnerability of the island. Not much of this was accounted for when environmental clearance was finally granted by the federal environment ministry in November 2022 via a letter issued by the ministry’s impact assessment division.

Forest clearance

Another parallel process going on simultaneously was for the stage 1 (in-principle) forest clearance (FC) for 130.75 sq km of pristine forest for the project. This was granted on 27 October 2022 making it one of the biggest such diversions in India in recent times. A key condition for forest clearance is the need for a detailed plan for compensatory afforestation, which the clearance letter states would be carried out in the state of Haryana. This has been questioned by many on ecological grounds asking how tree planting in a semi-arid zone can compensate for cutting of tropical forests in an island system more than 2000 km away.

Tribal concerns

Ajay Saini then elaborates the other key concern which is related to the rights and the livelihoods of the two tribal communities for whom Great Nicobar has been home for thousands of years – the Nicobarese that number about a 1000 individuals and the Shompen who number about 200. The latter is classified a particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG) and is a hunter-gatherer nomadic community critically dependant on the forests of this island for survival. The role of the institutions mandated with the task of tribal welfare is marked here by apathy and complete lack of concern. An example is the August 2021 letter by the A&N Administration’s Directorate of Tribal Welfare. It begins by assuring that the island administration will protect the rights of the tribals and goes on immediately to say that the Directorate will seek required exemptions(s) from the competent authority “whenever any exemptions” are needed “for the execution of the project”. At the national level too, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) and the NITI Aayog are seen to have completely abdicated their responsibility in the matter with multiple requests for information on impact on indigenous communities remaining unanswered.

Disaster vulnerability

For Janki Andharia, V Ramesh and Ravinder Dhiman, the central concern is related to the project’s location on a major fault line. The risk this poses, they note, has not been accounted for even in the final EIA report that the environmental clearance is based on. They have pointed out that the islands had experienced nearly 444 earthquakes in the last 10 years and the plan for the container terminal here “needs to be reconsidered”. Great Nicobar is not very far from Banda Aceh in Indonesia, which was the epicentre of the December 2004 earthquake and tsunami that caused unprecedented damage. The coastline of Great Nicobar saw permanent subsidence of nearly four meters as evidenced in the fact that the lighthouse at Indira Point now stands surrounded by water.

A critical juncture

Concerns over the project, discussions in the media and questions in the just concluded winter session of the Indian Parliament have thrust the remote, little known, little understood and even less visited Great Nicobar Island into the national limelight like never before. The only other time it had made it to headlines in national papers and in primetime news was when it had faced the unimaginable wrath of the earthquake and tsunami of December 2004. It is not even two decades since and it can only be considered Great Nicobar’s great betrayal and huge misfortune that this pristine island, its invaluable biodiversity and original human inhabitants, thousands of crores of valuable investment and more than 300,000 outsiders are deliberately and knowingly being put in harm’s way. There cannot be a folly more monumental than this.

Also see: The Andaman and Nicobar Islands need development by Ajay Kumar Singh, and ‘Limited intervention was in the best interest of the islands’: Interview with Ritwick Dutta, environmental lawyer, activist, author, and co-founder of advocacy group LIFE.

Pankaj Sekhsaria, PhD is Associate Professor at the Centre for Technology Alternatives for Rural Alternatives (CTARA), IIT Bombay, India. He has been researching and writing of issues of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for over two decades. He is also author of five books on the islands, besides several books on cultures of innovation in Indian engagements with nanotechnology and most recently on citizen science in ecology in India.

Published: 02/19/2023