From Honest Brokers to Thoughtful Partisans?

Taylor DotsonNovember 7, 2022 | Reflections

Given the harms of climate change, the pandemic, and similar crises, many scientists are not content with standing on the sidelines. But they face a dilemma: how to balance political action with the risk of appearing to inappropriately “politicize” science, which can undermine public trust. The problem is even starker wherever science is a needed input in contentious political decisions, where political opponents are likely to be on “high alert” for signs of politicization. How can scientists better navigate this difficult situation?

Movements like “The March for Science” often embrace the “linear model” of science policy. Credit: Amaury Laporte (CC BY 2.0).

Anything but Linear

In The Honest Broker, Roger Pielke Jr. roots the politicization problem in the “linear model of science,” the idea that fact consensus can or must drive political agreement and action. We find the linear model in the invocation to “follow the science” in debates over mandating the COVID vaccine or banning fossil fuel vehicles.

Roger Pielke Jr.’s The Honest Broker is a classic text regarding the role of scientists in politics. Credit: Tine Harden, Play the Game (CC BY-SA 2.0).

“Evidence-based” policy-making promises to free us from the morass of politics, but it is ultimately a trap. The linear model turns the ability to speak for scientific consensus into a political prize, offering the winner a privileged position in policy. Expertise ends up politicized in far more pernicious ways, usually discouraging dissent. For the Iraq War, the debate about “preemptive” military action was quashed by the selective use of intelligence, data meant to turn war into the only “realistic” option. Likewise, environmental scientists narrowly focus on the scientific missteps of climate contrarians like Bjørn Lomborg at the expense of the broader debate about “what sort of world we collectively wish to live in” and how to get there. The linear model deracinates politics, reducing it to an endless questioning of the opponents’ scientific bona fides.

Bjørn Lomborg’s climate arguments provoked considered controversy, but many scientists confused it for a work of science, rather than policy. Credit: World Travel & Tourism Co. (CC BY 2.0).

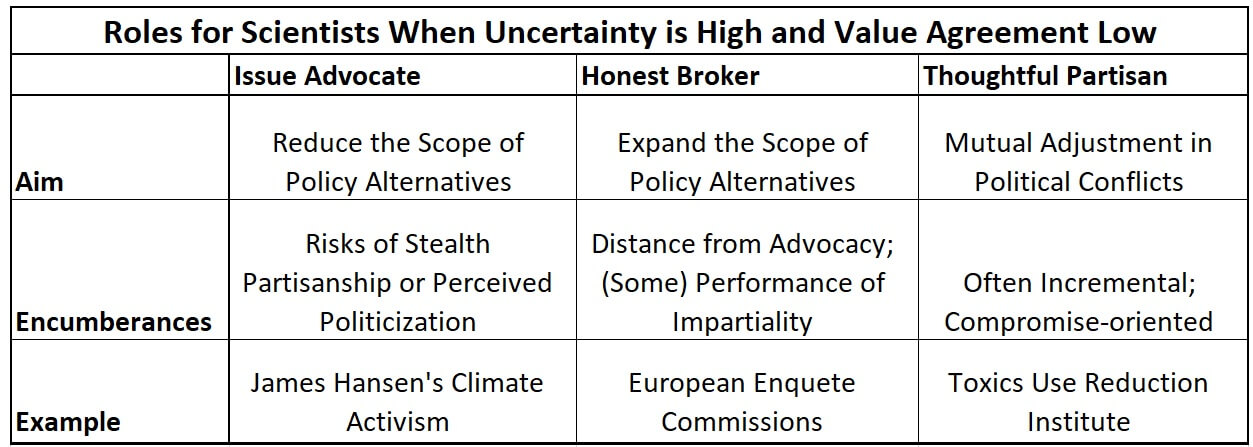

When uncertainty is high, and values are in dispute, Pielke argues that scientists have two options: issue advocacy or honest brokerage. Both roles recognize the intermingling of facts and values. But issue advocates invoke their scientific credentials in order to “reduce the scope of choice” about policy alternatives, like when James Hansen tells us that solving the climate crisis requires nuclear energy. Honest brokers, more often organizations than people, seek to expand the scope of policy alternatives. Climate brokerage requires laying out a variety of options, including both prevention and adaptation.

But issue advocacy is risky, easily becoming stealth advocacy when scientists depict themselves as simply “following the science” in the attempt to avoid political scrutiny. And lobbying, protesting, editorializing, and other forms of advocacy, in any case, invariably get painted by opponents as “politicizing” the science. While Pielke sees a place for both issue advocacy and honest brokering, the latter implicitly seems like the preferred option, at least so long as the linear model imprisons policy-making. Can issue advocacy be redeemed?

Partisan, but Thoughtfully So

Pielke wasn’t the first to point out the limits of expertise in policy-making. Yale political scientist Charles Lindblom also challenged the ideal of the non-partisan policy analyst, arguing that they aren’t capable of providing “non-partisan” research that supported “the public interest.” No expert has the time, information, or value-free perspective to determine the “correct” policy decision. Lindblom advocated substituting a claimed fealty to “the public interest” with what he called “thoughtful partisanship.”

Comparison of Potential Roles for Scientists in Public Controversies.

The adjective “thoughtful” is key to Lindblom’s proposal. The partisan analyst isn’t necessarily bigoted, ignorant, or duplicitous with the data. Like Pielke’s issue advocate, they recognize their work to be invariably guided by and supportive of some interests and values and not others. All analysis serves a particular constituency. But, unlike the advocate, the thoughtful partisan doesn’t seek to narrow public choice but to aid collective problem-solving.

Lindblom’s vision builds on a more expansive view of politics. Pielke imagines the honest broker helping public officials understand the potential tradeoffs of policy choices, for which the public only voices its preferences later on. It is a situation that Pielke likens to online travel portals but for policy alternatives, which still demands some performance of non-partisanship regarding the alternatives. Lindblom understood politics to be more dynamic and decentralized than the well-ordered world of honest brokering. It is one of coalitions constantly forming, breaking, and realigning, where policy pathways are discovered through political interaction rather than laid out by expert bodies. Lindblom called this the process of “mutual adjustment,” wherein the “coordination” of collective action achieves outcomes without authoritative decisions necessarily being reached by government officials.

Lindblom’s politics directs us to not just think about intermediating the worlds of science and policy but also between different publics. Scientists’ role within this second kind of brokering process remains underdeveloped. How could knowledge production facilitate mutual adjustments between opposing partisan groups? This might mean researching and promoting less-than-ideal policy options in the service of coalition building.

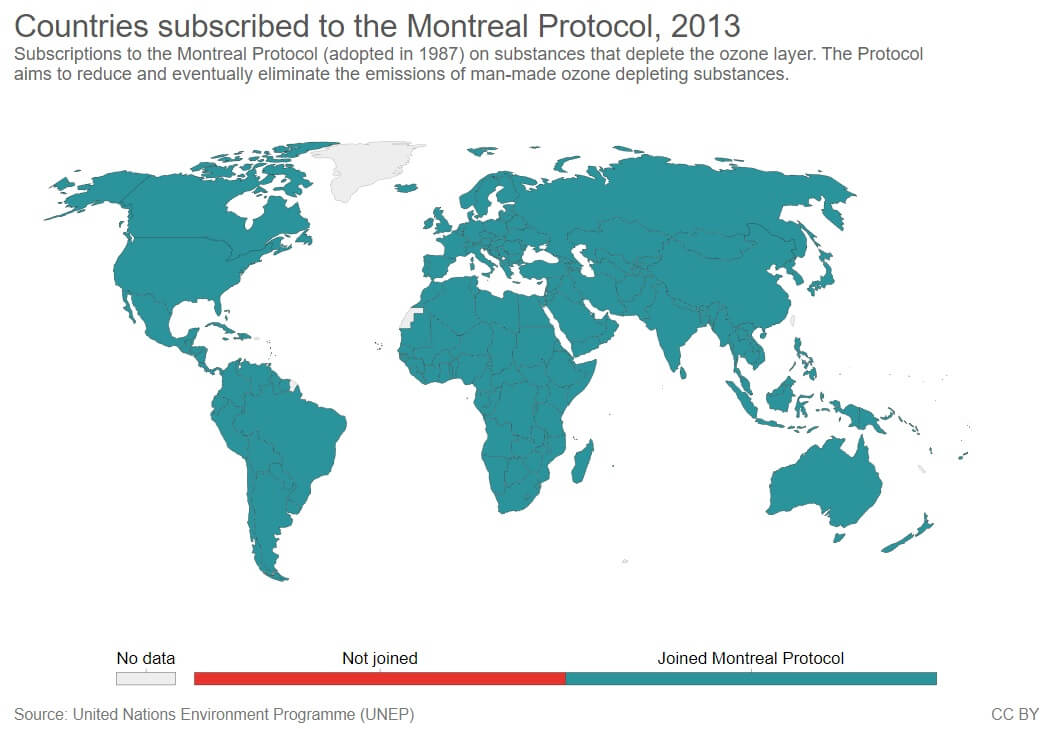

In the case of climate change, declarations that saving the planet demands forgoing animal products might be deemphasized in favor of trying to make plant-based protein sources cheaper and more convenient. This would be a calculated adjustment, aiming to secure a partial victory by anticipating opposition. Such strategizing learns from the Montreal Protocol to ban ozone-depleting CFCs, which was enabled by the availability of substitutes. Some firms had already begun a phase-out in response to public pressure; Greenpeace even hired engineers to develop a CFC-free refrigerant. National and global bans arrived largely after a process of mutual adjustment lowered the political stakes and built up a supportive coalition.

The Montreal Protocol is a rare case of successful and rapid mutual adjustment. Scientists and engineers played a key role in the process. Credit: Our World in Data (CC BY 3.0).

Politics of the Possible

Examples like the Montreal Protocol remind us that neither political interests nor possible futures are fixed. If democracy were simply a matter of triangulating between established preferences and knowable end states, experts would be capable of divining optimal policies. Rather, democracy means mutual learning, reconsidering what previously seemed unthinkable and searching for ways to reconcile what appear to be incommensurable interests.

The Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI) is an inspirational model for achieving thoughtfully-partisan technoscience. Firms face fees for toxics use, a pretty standard policy mechanism. But that alone can lead to perverse outcomes, a failure in mutual adjustment. Because they don’t necessarily value detoxification, firms may be tempted to feign compliance via secrecy or by making regrettable substitutions, replacing one toxic with an equally hazardous but less well-known one. TURI offers companies another way out by working with firms and regulators to discover cost-effective, less-toxic alternatives, lessen the barriers to adoption, and develop implementation plans. As Steve Rayner and Daniel Sarewitz note, former enemies were turned into collaborators: “firms…became constituents for safer chemicals.”

Traditional toxic chemical regulation is high stakes and highly uncertain, existing exactly where “linear model” science policy falters. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency scientists must prove the risk of harm and then issue costly chemical prohibitions. TURI explicitly breaks with this model. Freed from authoritatively establishing the existence, extent, and seriousness of the toxics problem, scientists can work more directly with stakeholders to make previously unimaginable alternatives believable. This is no simple task, for even designers at the relatively “green” carpet manufacturer Shaw Industries had to be convinced of the feasibility of environmentally-friendly products by company VPs.

TURI’s scientists accomplish no small feat of democratic mutual adjustment. As Lindblom would put it: they “create opportunities for collective action that did not exist before.” Sidestepping the presumed need for scientific or value consensus on toxic chemicals, expertise can be leveraged toward finding some small step forward. Progress in detoxification is achieved in the absence of authoritative assessments and prohibitions, instead setting up the conditions for collaborative partisan interaction.

No doubt, mutual adjustment via partisan science tends toward incremental rather than dramatic breaks with the status quo. But decades of calls for radical climate action, buoyed by scientists’ issue advocacy, have rarely produced the sought-after transformative changes. And honest brokering can seem to demand too much political distance, or might even appear feckless in the face of worsening polarization and policy inaction. But scientists are not limited to advocating as “the voice of science” or enumerating policy alternatives. They could contribute facts, analysis, and discoveries to the task of partially reconciling political conflicts. And that may prove to be their most necessary and effective role.

Taylor Dotson is Associate Professor of Social Science at New Mexico Tech. He is a Fulbright Scholar and author of two books: The Divide and Technically Together. His current research focus is the politics of biodiversity.

Published: 11/07/2022