Space Forces and The Making of (Other) Worlds: An Interview with Fred Scharmen

Réka Patrícia GálDecember 20, 2021 | Reflections

Space colonization is undertaken in the name of boundless exploration and the promise of encountering and creating strange new worlds. But what sort of social, political, and technological possibilities do these new worlds carry? This is what Fred Scharmen’s latest monograph, Space Forces: A Critical History of Life in Outer Space (2021), sets out to examine. Scharmen teaches architecture and urban design at Morgan State University’s School of Architecture and Planning. In Space Forces, he examines seven different paradigms of space colonization to unveil how various cultural contexts and worldviews influence the type of futures authors hope to bring forward – starting with the work of Russian cosmist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in the 1890s and ending with the narratives constructed by contemporary entrepreneurs such as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. he book’s structure imaginatively juxtaposes each narrative with that of another contemporary to offer an implicit critique and a contrast that highlights the assumptions about the nature of nature, humans, and technology in these constructed worlds. As a result, Scharmen is able to not only critically probe the visions of space colonization that hinge on political ideals wishing to maintain the status quo, but also to point out hopeful and loving alternatives that embrace the diversity of human, as well as non-human, experiences.

In this interview, Scharmen talked to us about the constructive power of science fiction, how an architectural perspective can inform critical studies of outer space, and how technological idealism has shaped visions of off-world existence.

The cover of Fred Scharmen’s latest monograph, Space Forces (2021).

Réka Patrícia Gál (RPG): The book’s analyses carefully oscillate between looking at scientific and science fictional worldbuilding. By doing so, the question of mediation emerges as a powerful analytic, which shines in your chapter on NASA and the emerging conspiracy theories around the Moon landings. For example, you call NASA “a producer of systems and a producer of images, acting in science fiction one moment, and producing scientific facts in another.” (2021, 179). Discussions about space colonization are so often steeped in a rhetoric of plausibility and objectivity. In this context, what sort of power do fiction and speculation hold?

Fred Scharmen (FS): NASA, I think, has always been back and forth across that line. They would say, “Hey, we’re really going to do this and it’s going to happen in five years, and this is what it’s going to be like” while also countering it with “Okay, well, we’re not science fiction, we really do make things happen.” But they do utilize a lot of the means and methods of science fiction to build constituencies, to build interest and support. It is an interesting connection to the kind of masculine rationalist narratives surrounding some NewSpace practitioners like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. I think the NewSpace industry is anxious about the stories they tell to different audiences that institutions like NASA don’t have, don’t need, or maybe don’t recognize. They have to not only build a political support base, almost like fans, which NASA finds really easy, but they also have to find investor audiences. This demands a certain kind of plausibility: you don’t want to put your costly satellite on top of a rocket that is not going to plausibly launch to orbit.

So they have to speak to investors, they have to speak to the public, and they have to speak to a customer base. Whereas NASA, as a public institution, only really needs to have sort of one assumed audience, which is the wide-eyed kid who is overcome with a sense of wonder from the power of rockets and the majesty, and heroism, and mystery of spaceflight. NewSpace has so many more different audiences that they’re all trying to address simultaneously so that their messages sometimes become contradictory. To connect with that sense of wonder, NewSpace companies tell these narratives of “spreading the light of consciousness” in the universe, but that can build this contradiction between indefinite extension of the world we have now as a backup plan, versus the possibility for a radically new world in which all kinds of new ways of life become possible. That is not something you want to tell investors or customers: you don’t want to scare investment capital by saying “things are going to radically change once we get to space,” because investment capital, in particular, wants predictability, reliability, and repetitiveness. NASA doesn’t have to tell such complicated stories to so many complicated audiences.

RPG: As an architecture and design scholar, how did you come to focus on space science and science fiction? What has it meant for you to work at the intersection of these fields?

FS: Moving towards more abstract issues within research and scholarship, but with my background as an architect and designer, has allowed me to reconnect with things that are essential to spatial practice generally, but also to architecture specifically. One of my favorite examples is that air is designed. And all of the lines that we as people on spatial practice disciplines like to draw on paper are made up of matter. This means that we have to be explicit about their characteristics and qualities. Architects write documents called specifications, where you describe what you drew in detail. Where do we source it? Does it make a noise when you knock on it? How heavy is it, how tall?

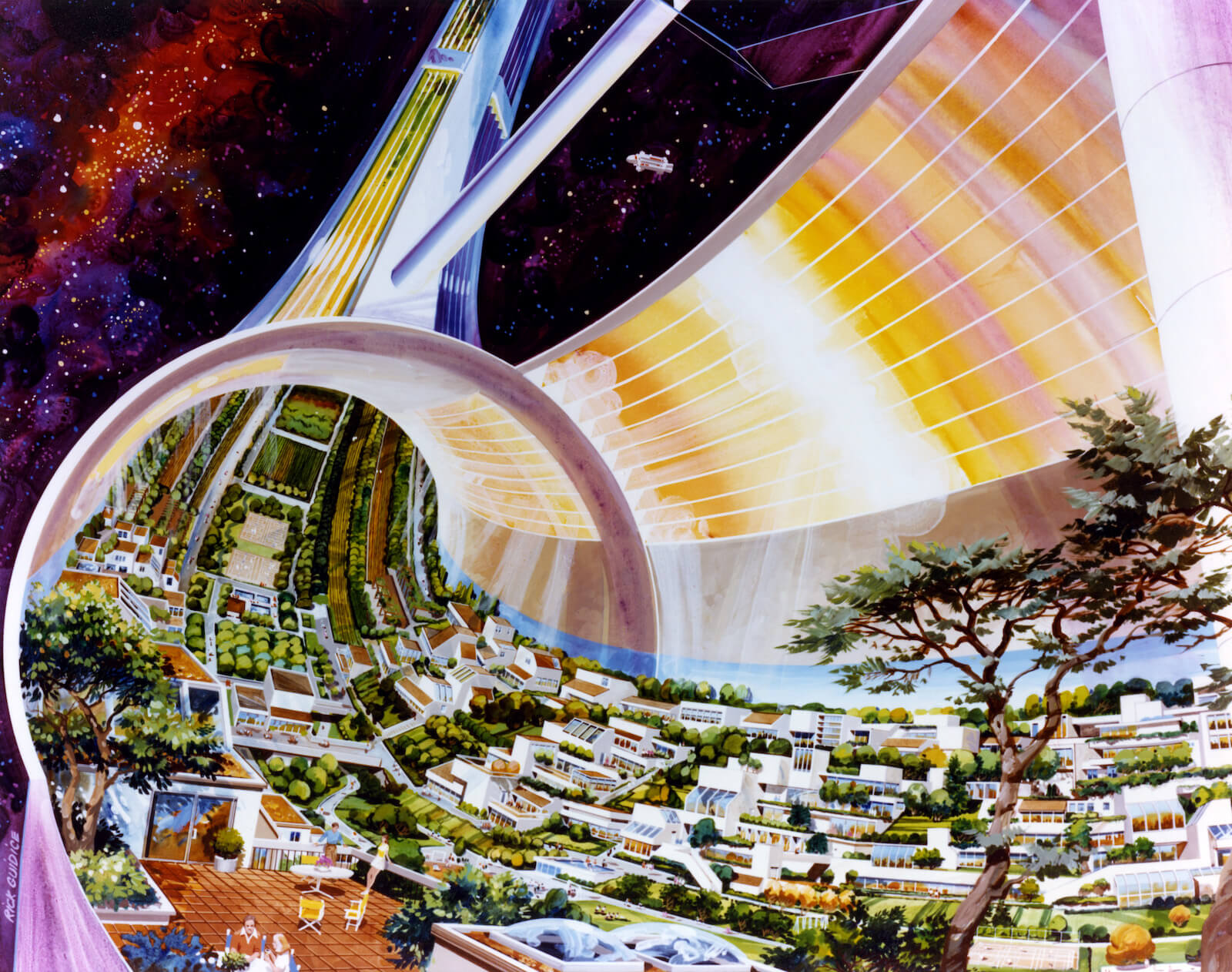

Torus Wheel Space Colony imagined by artist Rick Guidice (1975). Courtesy of NASA Ames Research Center.

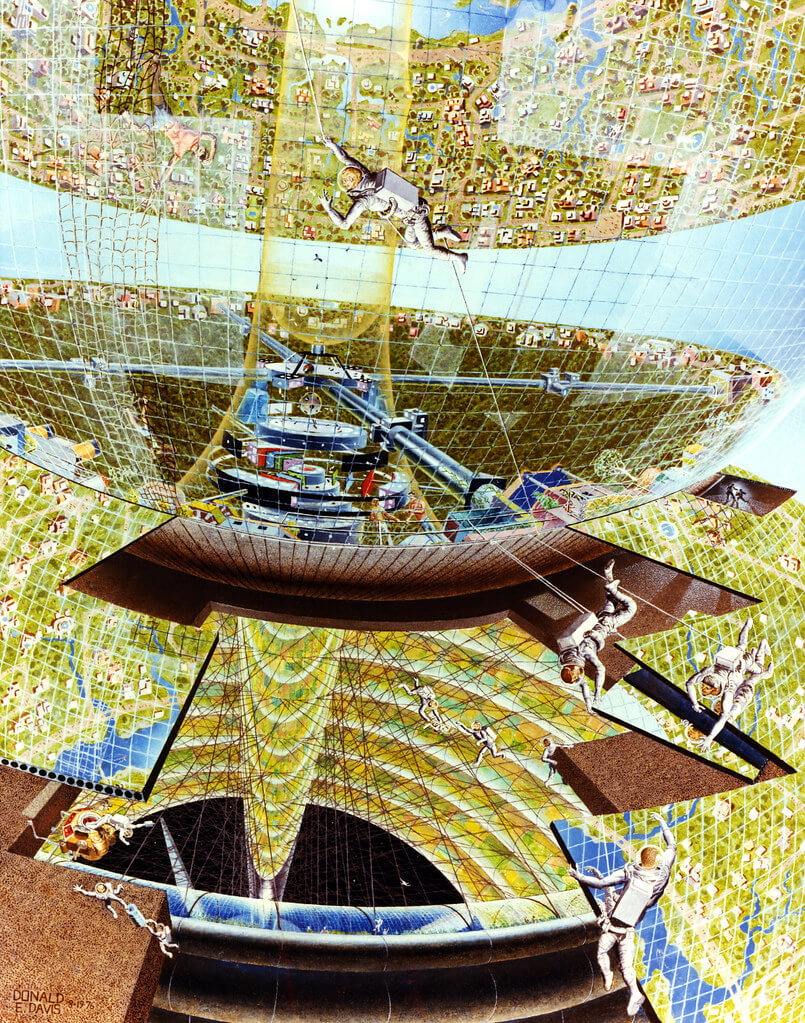

So looking at space colonization through an architectural lens brings the necessity to specify back to the forefront, to the point where I call it “a crisis of specificity.” Suddenly, everything must be specified. Even gravity if the space habitat is spinning, and what the air is made of. Everything needs to be chosen, specified, and quantified before leaving the habitat. It is a million trolley problems, all at once. And some of those consequences are the literal exclusion of people who cannot be in the space you’re producing. The culture of creating a room creates a culture within it. So the culture informs how the room is created, and then that room informs its own culture, which is composed of the people who are in that room or who can be in that room, or who that room invites into itself. So how culture makes space and how space makes culture is really interesting.

RPG: A significant part of your project deals with unveiling the understanding of technology each of these narratives puts forward. I found your investigation of the relationship of technology to human labor in these narratives illuminating: We have the work done by the replicants in Blade Runner (1982), the robot helpers in Silent Running (1972), Bernal and Bogdanov’s discussion on automation, and Fedorov’s hopes of weather manipulation unleashing solar energy and freeing coal miners from work. The most striking example to me is Wernher von Braun’s claim that technology is “the only means offered by God whereby we may strip off the curse of slavery” (2021, 90). You contrast this with the material reality in which, for example, von Braun’s V2 rocket was produced by prisoners in the Dora-Mittelbau Nazi concentration camp. How does the utopianism of these narratives relate to invisibilized, gendered, and racialized human labor? To what extent does it depend on this labor?

FS: This is interconnected with the redefinition of certain subjects as not human or less-than-human. Both in the stories like Blade Runner where the applicants are not given human status, but also in Nazi narratives that literally classify whole sections of humanity as being sub-human. But other capabilities get opened up by utilizing that kind of categorization. This is connected to the narratives Afrofuturists like Ytasha Womack have conceptualized to describe how a technology of blackness is imposed as a technological cataract of categorization that allows a dominant culture to manipulate, mobilize, and mechanize whole other cultures and racial identities. I love that you brought in this von Braun quote, that technology is a kind of God-given tool that strips off the curse of slavery because it is also the exact the same thing that applies the curse of slavery as well. If you read that quote back through the lens of Afrofuturism, you can see how much work the conception of God is doing there.

The labor thread is not so explicit in the book. Still, I have been thinking about that a lot ever since, for instance, about how the utility of idealism occupies a place in a long line of propositions about the end of work and the end of scarcity. There are a lot of narratives that claim that if we just mobilize this new technological capability—the skyscraper, the automobile, the personal computer, or space settlements, if we just invest in this, then the benefits will accrue to all. They will trickle down, eliminate scarcity, and liberate a working-class and everyone else from the drudgery of labor. Instead, the opposite keeps happening. There are, in fact, science fiction stories about people who say, “I haven’t paid my air bill this week. I live in space, and it’s a company town, and I haven’t been able to afford you know this week’s ration of oxygen.” There’s no such thing as free air when the air is manufactured.

Construction of a Bernal Sphere Colony, imagined by artist Don Davis (1976). Courtesy of NASA Ames Research Center.

RPG: Your book highlights some narratives that oppose the mainstream desires for colonizing outer space as a way to dominate – be that the forces of nature, or other humans, or aliens. You pay attention to the generativity of staying with the mess, Arthur C. Clarke’s love of the weirdness of nature, Rachel Armstrong’s sketches of space colonization that focus on mud, and bacteria, and mold as primary objects in the discussion. How do these sorts of narratives shape your understanding of space colonization?

FS: Rachel Armstrong has a terrific science fiction novel called Origamy (2018), about a messy starship. She deals with the entanglements and the messiness to depict a weird multi-dimensional human future in space. For me, that is the blurry boundary of the light of consciousness; it’s tied in with questions of what constitutes a world. In a simple sense, our microbiome may or may not have more to do with your mood on a given day and your external stimuli. Whatever your gut bacteria are into that day may determine more about how you go through the world than anything else. It brings up questions about resurrecting the body and a cosmic future. Do you resurrect the gut biome too? The messiness questions the hard limits to that high modernist worldview and those perpetually sterile science fiction futures. Where’s the mud? Where is the slime? That is the light of consciousness too, and even from a utilitarian perspective, if you tried to take an inventory of what makes a minimum viable ecosystem, if you left out the bugs and the disease, you’d find a couple of generations down the line that we actually needed all of that. So it is really important to understand what each of these stories has a bias towards, and what model of the future they depict as a result.

RPG: Thank you for your time, Fred!

Réka Gál is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Information at University of Toronto and a Fellow at the McLuhan Centre for Culture and Technology. Her dissertation maps the modalities of technological maintenance and care labors aboard the International Space Station and its precursor Skylab, contextualized through the gendered and colonial history of human spaceflight, ultimately tracing how normative practices of care work from Earth are replicated and recontextualized under circumstances of extraterrestrial dwelling.

Published: 12/20/2021