Climate engineering: An examination of the skies through the lens of art, and culture

Tina SikkaNovember 29, 2021 | Reflections

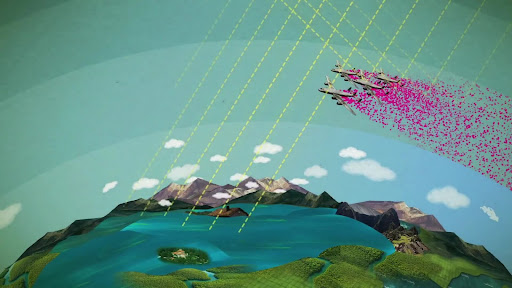

Climate engineering can be defined as the intentional technological manipulation of the climate in order to reverse the effects of global warming. Advocates of solar climate engineering in particular hope to replicate the cooling effects of volcanic eruptions by intentionally spraying particulates into the atmosphere to create a comparable ‘aerosolic barrier’ which would reflect the sun’s harmful rays away from the earth. One of the less considered consequences of solar climate engineering, often in the list of possible consequences but not examined in-depth (at least not in the scholarly literature), is the impact of a changed atmosphere and the effect it will inevitably have on cultural expression and our embodied, relational selves. Because solar climate engineering cannot be tested without actually deploying it, particulates and all, past volcanic eruptions have been used by scientists and climate modellers as natural analogues to extrapolate its possible effects. Research has shown that the very sulphate particulates volcanoes emit during large eruptions, like the Phillippine’s Mount Pinatubo did in 1991, resulted in demonstrable reductions in global temperature. While there are a plethora of academic and media texts that study the safety and efficacy of solar climate engineering, including from me, here I reflect on a specific dimension of a likely consequence – that of the whitening of the skies and changing atmosphere – rooted in art, literature, and human affect.

A technofix for the climate- Atmospheric geoengineering (Solar Radiation Management) – Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

In a manner similar to the use of historical natural (volcanic) analogues to assess the likely impact of climate engineering, I argue that it is also important to examine the cultural production that took place during these events – particularly ones that take up the skies in their work. Of particular interest is how artists of all sorts talk about, write about, and visually depict these transformations. What is most intriguing to me is, first, how the skies became a character, even a muse, in certain artistic outputs and, second, how the ways in which we think about the consequences of climate engineering might press us to think more closely about the experiences depicted in said art going forward.

One of the things we can say for sure is that the heavens as a site of possibility and futurity, replete with its changing hues, sounds, and precipitations, shapes the moods, wellbeing, engagements, and activities of both humans and non-humans. The sombre, fearful, even apocalyptic representations reflected in a variety of mediums following massive volcanic events, presages what may come culturally in a post climate engineered world – to say nothing of what this might mean for the cultural lives of everyday folks embedded in communities for whom the blueness of the sky and vitamin D producing sun forms an important and sustaining part of daily life.

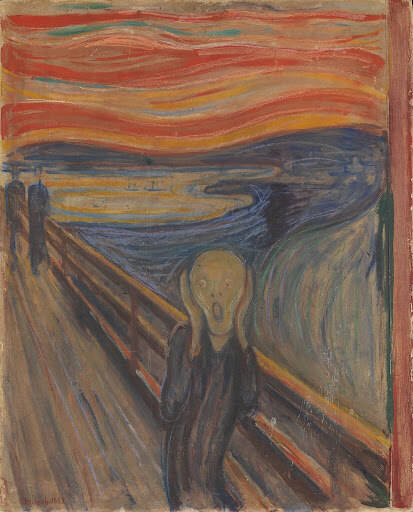

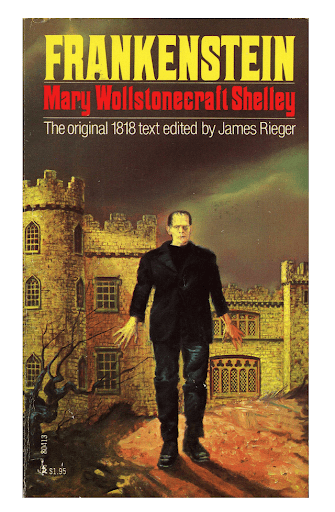

What is of particular interest to me is how the post-eruption changes to our skies, weather, and climate is express by artists and writers like William Turner, Edvard Munch (“The Scream” in particular), and Mary Shelly (in Frankenstein) – all of whom produced depictions and reflections that allude to the whiteness of the skies and the unanticipated changing weather. Munch described these changes as “A scream passing through nature,” while Mary Shelley, as legend has it, was so jarred by the weather extremes caused by Indonesia’s Tambora volcano (1815) that she situated the story of Frankenstein at the beginning, “with the search for new, more habitable lands because of environmental anxieties” – specifically a prolonged winter. Lord Byron’s poem Darkest Summer is one I find particularly moving in its description of atmospheric bleakness:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

And,

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain’d;

Cover Art for Frankenstein by Mara McAfee; Pocket Books, 1976

The eruption of Mount Tambora, which, again, provided the context from which these works emerged, is not a new phenomenon and was mirrored over a century earlier by the work of Samuel Pepys who wrote:

“It is strange what weather we have had all this winter; no cold at all; but the ways are dusty, and the flyes fly up and down, and the rose-bushes are full of leaves, such a time of the year as was never known in this world before here.” (Pepys quoted in Brown, 2015)

It is thought many of Pepys’ written observations, as reflected in his diaries, were shaped by changes brought about by a major volcanic eruption in La Palma. Similarly, the apocalyptic work of John Milton, according to David Higgin, influenced writers like Horace Walpole, Gilbert White, and William Cowper who, through reading Milton’s allusions to life after the 1669 eruption of Italy’s Mount Etna, found “a powerful way of understanding the entanglements of culture and climate at a time of national and global crisis.” Milton wrote:

…the shattered side

Of thund’ring Etna, whose combustible

And fueled entrails thence conceiving fire,

Sublimed with mineral fury, aid the winds

And leave a singèd bottom all involved

With stench and smoke…

What does this all portend for us? One of the things we might consider – particularly as the forces and flows of climate engineering research are pushed to the fore (and on top to how this form of intentional climate manipulation may impact the ozone, oceans, and weather) – is how it will shape cultural output and, by extension, us as affective, embodied, and relational human beings. What we might consider, as I have done, is what previous periods of ominous and dismal cultural output – much of which is brilliant, evocative, and moving – tells us about how the rest of humanity will react, feel, and relate to an intentionally transformed skyscape. While scientific research of climate engineering is effective in determining probabilities, ranges, and perturbations, it is much less aware of significant intersectional, humanistic, and cultural consequences. I myself have written extensively about issues of power, race, gender, and class as it relates to these new climate technologies, but never culture. Whether it takes the form or weariness, ennui, or the more medicalised seasonal affective disorder, what we can say for sure is that any consideration of climate engineering and its effects needs to consider all forms of socio-cultural impact, of which art and culture constitutes an important analogue.

___________________________________________________

Dr. Tina Sikka is currently a Lecturer in Media, Culture and Heritage at the University of Newcastle in the UK. Her current research interests include the ways in which gender, race, and culture intersects with science and technology using food and environmental technologies as case studies. She also has expertise in sexuality studies as it relates consent, gender-based violence, and restorative justice and as well as in EDI and decolonial research practices. She has written two books, numerous articles and has taught Communication and other Social Science courses throughout Canada and in the UK.

Published: 11/29/2021