The Controversial Lion: A Tale on the Mapping of Sociotechnical Debates

Tommaso Venturini and Anders Kristian MunkNovember 1, 2021 | Reflections

Controversy analysis has been around since the 1970s as a technique to investigate the role of science and technology in society as well as the role of politics and economy in technoscience – and in fact the impossibility to separate the two. In the last two decades, this established STS approach has been revived by the encounter with digital methods and the way in which electronic media and online platforms increase the visibility of controversies and facilitate their traceability.

In a recent field guide (Controversy Mapping. A Field Guide. Polity, 2021), we inspect the roots of controversy mapping in actor-network theory and digital methods; explore its cast of actors and issues; introduce a series of quali-quantitative techniques for curating digital and non-digital records; discuss how to represent sociotechnical debates; and how to intervene in them. This short essay offers an amuse-bouche and a snappy introduction to our book. It summarizes some of its key ideas with an embellished metaphor, almost as a bed-time story.

The King under the Baobab

One day at dusk, when the animals gathered under the big Baobab by the watering hole, Rhino spoke up and asked Lion: “How did you get to be our king? Who decided that?” Lion smiled ceremoniously and replied: “No one decided it. I am king because I am the strongest and my strength offers protection. That is the Law of the Savanna”. The animals nodded, but the question took root in their minds and the next day at the Baobab, Rhino spoke again: “True, you have your claws and teeth, and your majestic mane, I grant you that, but who said that strength should be measured by these attributes? I have my horn, and a skin that is tougher than yours, why should I not be king instead?”

“You are not wrong, my friend,” replied Lion with a smirk, “and in fact, why should strength decide at all?” He paused and looked around at the other animals: “Rabbit has long ears and can hear danger coming. Monkey is cunning and can foil traps and snares. Maybe one of them should be king instead?” The animals pondered his words. “Maybe we should be kings”, said the Ants, “we are well organized, and that is what a community needs the most”. “Or maybe I should be king”, said Giraffe, “I have the longest neck and can spot food and water from far away”. “Or maybe I should”, said Elephant, “for I am the biggest”. “Or me”, said Cheetah, “for I am the fastest”.

“All excellent points”, grinned Lion, “and they all seem equally valid to me. Keep discussing and resolve your differences. The moment you agree on my successor (but not a moment before), he or she will have my crown. Take as long as you need!”.

It is in moments of controversy that the entanglement of knowledge and politics becomes most obvious. Lion has landed himself squarely in the middle of a sociotechnical debate, even if this is not necessarily to his disadvantage. Under normal circumstances, the simple reference to implicit conventions of the ‘Law of the Savanna’ would settle the claims to the throne. As long as no one questions how strength is measured, there is no need to resort to it. And even when someone does question the consensus, politics does not turn immediately into a fistfight. Instead, it becomes a contest of competing claims, in which Lion shrewdly applies his stalling tactics of perpetuating uncertainty.

This is a familiar dynamic and one that can be broken down into three main components.

- First, it is easier to introduce or stop a vaccination program, an energy policy, or a set of privacy regulations if some form of scientific evidence can be fielded for or against them and disseminated through the media.

- Second, tussling in a controversy is not only a matter of rhetoric and evidence but also of reconfiguring the material situation to gain the upper hand.

- Finally, and it’s a key tenet of controversy mapping, there is no easy way to decide beforehand which piece of knowledge or technology will legitimately sway the debate – no way of ruling out positions or arguments before investigating them, of junk news (Venturini, 2019) and infodemics (Simon & Camargo, 2021).

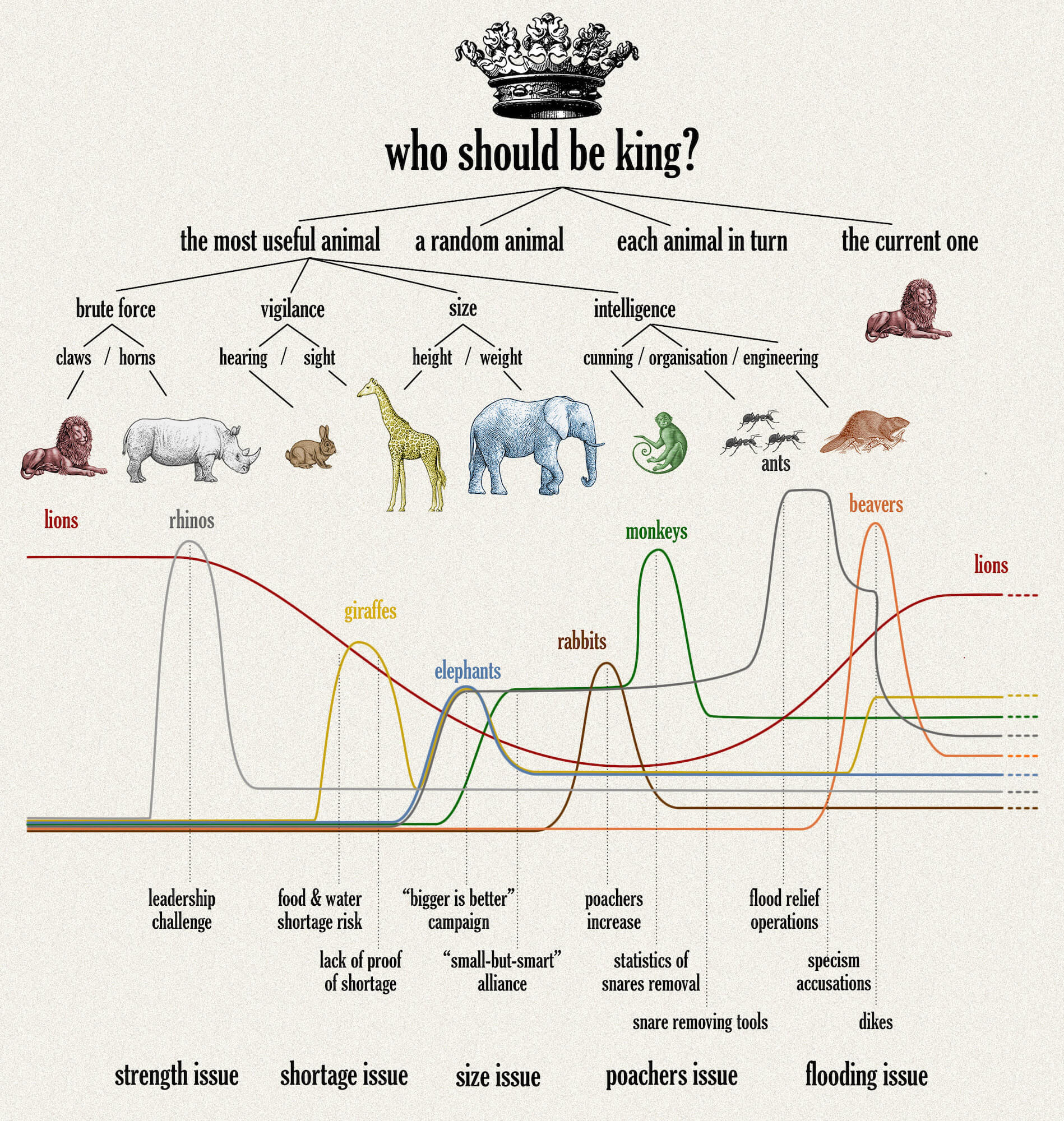

Because the discussion of these three components of sociotechnical controversies as they unfold under the Baobab requires more space, the complete analysis of the controversy in the Savannah is available here. The image below summarizes the analysis in the visual language typical of controversy mapping.

Figure 1. A simple mapping of the Baobab controversy. Credit: The authors.

Tommaso Venturini is a researcher at the CNRS Centre for Internet and Society, associate professor at the Medi@lab of the University of Geneva and founding member of the Public Data Lab. Tommaso’s research lies at the intersection of media studies, science and technology studies (STS), and digital social sciences. His activities focus on digital methods; controversy mapping; online public debate; social modernization. He is the principal investigator of the projects DOOM and CAIAC, team leader in the projects ScientIA and CulturIA and has coordinated the projects EMAPS and MEDEA. His research focuses on the troubles of digital communication, attention cycles, and the secondary orality of online platforms. All Tommaso’s projects and publications are available here.

Anders Kristian Munk is associate professor and director of the Techno-Anthropology Lab at the University of Aalborg in Copenhagen and founding member of the Public Data Lab. His research focusses on public knowledge controversies and the role of digital platforms for democratic debate. Anders has a particular interest in the development of new digital methods at the interface between ethnography and computational techniques for data curation, analysis, and visualization, including how to involve stakeholders and citizens in data work.

Published: 11/01/2021