Asian Medicine and COVID-19: Introducing a Special Issue of Asian Medicine

Michael Stanley-Baker and Ronit Yoeli-TlalimOctober 25, 2021 | Projects

Figure 1 Hope. Katarina Sabernig. Asian Medicine 16, 1 (2021); https://doi.org/10.1163/15734218-12341481

Asian medical traditions have a great deal to offer in the current pandemic, but articulating this within the current climate presents challenges not all practitioners have the time for. This special issue of Asian Medicine reports on responses to COVID-19 and other historical epidemics in a number of Asian regions, with the intention to provide some epistemological breathing room amidst the flurry, and to reflect on the potential usefulness of these interventions.

Reporting and scholarship on the COVID-19 pandemic has focused overwhelmingly on its biomedical, epidemiological and political aspects, but very little literature has focused on how medical cultures outside of biomedicine have responded. The anxiety to quell anti-science and conspiracy theory has created a binary between science and quackery, and failed to acknowledge that the epistemological spectrum of medicines in the world is more nuanced. Traditional medicines have robust, long-standing cultures of practice, experimentation and verification, of institutional authority, of adjudication of efficacy within which they have developed responses to epidemic. They emerge from longue-durée histories of epidemic, medicine and cultures of care, and their rationales and approaches can be understood on their own terms and implemented and integrated safely, authoritatively and productively.

Figure 2 Herbalists in Wuhan using newly developed high-volume drug preparation system. Credit: Webinar by Ochs and Garran.

The memory of pandemic and epidemic has been short-lived in the popular media and policy research, stretching back only 100 years. While historians of Europe and global medicine have tapped on the black death as touchstones, in this issue it is practitioners, not just historians, who draw on herbs and recipes disease terms that emerged as early as 200 CE, and consider how to apply them in the present. The long history, theories, and therapies of epidemics, have been inscribed in various Asian medical and religious writings of various genres, exemplified in this issue by Di Lu; Triplett; McGrath; Tidwell and Gyamsto. The flexibility and adaptability inherent to the Asian medical systems described here have allowed the interpretations and ensuing therapies, in the many months, and amongst the vast number of population, when and where nothing else was available, or indeed forthcoming.

Figure 3 Daegu Haany University Hospital Korean Traditional Medicine Telemedicine Centre. Credit: Webinar by James Flowers

As Timothy Brook (2020) pointed out lately, collective memories of pandemics differ significantly between Europe and Asia. In order to understand how and why we as a global society, can understand and approach pandemics in a more global way, we need to understand, probe and somehow join up these collective memories. Asian medical systems have been able to provide explanations for COVID-19 which biomedicine—at least for quite some time—could not. Also, for a very long time—and in many places on the planet: still to date and for long to come—these were the only explanations, or in any case: the only therapies available. Those explanations, derived therapies and policy positions were developed by institutions, communities, and practitioners in China (Ochs and Garran), Korea (Flowers), New York (Craig et al) and through global networks of traditional medicine communities (Tidwell and Gyamtso). Craig and her team also document other aspects of how the Sowa Rigpa doctor, Dr. Kunchog, treating his patients in New York at the height of the pandemic, was able to provide explanations and care where biomedical doctors could not. In addition to the articles linked above, please see the webinars by Ochs and Garran on the response in China, by Flowers on traditional practitioners in Korea, and by Joshua Park on the role of Chinese medicine in communities of colour in the US.

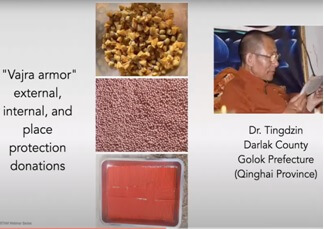

Figure 4 Sowa Rigpa protective medicine. Credit: IASTAM Webinar by Tara Alberts

The Asian understandings of COVID 19 described in these papers deal not only with physiological multi-organ aspects that in biomedical terms made little sense, but also with the mental and psychological aspects which are a central crucial element in the way Asian approaches address illnesses more generally. The doctor-patient interactions described in many of the papers in this special issue, involve not only the physiological aspect, but also the mental health and emotional health aspects, central, of course, to Asian medical systems at large (discussed especially by Craig et al., Tidwell and Gyamtso, and Flowers). Hence, for example, Craig and her team describe how the Tibetan physician they had documented, was mindful of treating not only those who have contracted COVID-19 directly, but also those suffering from other profound health effects of the pandemic: depression, anxiety, insomnia as well as musculoskeletal problems that have arisen from being confined to small living quarters and not getting exercise.

Figure 5 Star of Heavenly Punishment (Tenkeisei天刑星) Nara National Museum Collection, Sign. 1106. Katja Triplett, Asian Medicine 16.1, https://doi.org/10.1163/15734218-12341490

These subtler dimensions of the impact of pandemic are the motivation for other papers which address religious responses to disease, which span pre-modern China, Japan and Tibet. Papers by Triplett, McGrath, Capitiano and Lu point to broader ways in which disease is conceptualised in the public imagination, how risk and aversion, fear and grief are processed, and how existing cultural resources are utilised in new forms to cope with new crises. Visualisation of the pathogen took form as demonic beings, and their spatialisation took the form of directional rituals and warding rites to fend off disease.

An important historiographic innovation is attempted in Lu’s paper, one of the first attempts to collect traces of zoonotic theory in Chinese sources. While it never became the subject of concentrated medical reflection, Lu demonstrates the idea as intuitive in a number of contexts and types of primary source, including poetry, animal husbandry, government documents, religious imagery as well as pharmacological tracts.

We are beginning to see a more open approach, which is in publications, such as Nature, where in March 2021, Hetan Shah, the British Academy’s Chief Executive, argued that in our attempts to recover from COVID 19, we need to go beyond the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) disciplines, and take into account “human behaviour, motivations and culture”, stressing also that “policymakers were overly focused on evidence from randomized control trials, rather than the observational, qualitative evidence that social sciences are steeped in” and that “had governments been set up to listen to the advice of historians, they could have helped us to think about what worked in past pandemics.”

Helen Tilley has pointed out that COVID 19 has provided a focus on how “home-grown” medical cultures can espouse a trust in forms of practice and experience that challenge more dominant techniques of scientific proof, opening the door to more dynamic forms of “polyglot therapeutics”, and unsettling sharp boundaries of what has previously been labelled “effective” and “ineffective”. Crises, and an inability to respond to them, invite such an opening of doors and minds. This much we have learned from past pandemics. Now that the door has been opened, we can also observe what gets in, and what does not; who sits at the doorway and why. It’s going to be interesting, and this Special issue is just the beginning.

Michael Stanley-Baker is an assistant professor in History at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, jointly appointed in Medical Humanities at Lee Kong Chian medical school. He holds a PhD in Medical History from University College London, and a clinical degree in Chinese medicine, and has held research appointments at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, Academia Sinica, and the Needham Research Institute, among others. He has served over ten years as Treasurer and then Vice-President of IASTAM. He is co-editor of the Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine and of Situating Religion and Medicine Across Asia, and PI of the digital humanities projects Drugs Across Asia and Polyglot Medical Traditions in Southeast Asia. He is currently working on a monograph on the gradual separation of medicine and religion in early imperial China.

Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim is a Reader in the History Department at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research deals with the transmission of medical knowledge along the so-called ‘Silk-Roads’. She is the author of ReOrienting Histories of Medicine: Encounters along the Silk Roads (Bloomsbury, 2021). She is an associate editor of the journal Asian Medicine (Brill). She co-edited (with Anna Akasoy and Charles Burnett): Rashīd al-Dīn: Agent and Mediator of Cultural Exchanges in Ilkhanid Iran (2013); Islam and Tibet: Interactions along the Musk Routes (2011) and Astro-Medicine: Astrology and Medicine, East and West (2008).

Published: 10/25/2021