Botany, Trade and Empire: Exploring the Miscellaneous Reports Collection at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Aimée Crickmore and Rachael GardnerAugust 2, 2021 | Projects

The Miscellaneous Reports Collection is a vast archive of botanical history that, until recently, remained in an uncatalogued and deteriorated state until a project to revitalize the collection started in 2018. Here, Project Conservator Aimée Crickmore and Project Archivist Rachael Gardner discuss their work on the project.

What is the Miscellaneous Reports Collection?

The first thing to know about Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports Collection is that it isn’t actually ‘miscellaneous’ at all. It is a distinct collection of unique archive material and rare printed reports containing information relating to economic botany and the administration of botanic gardens around the world. It was created during the course of Kew’s work in the 19th and early 20th centuries and forms a significant part of Kew’s own official archive.

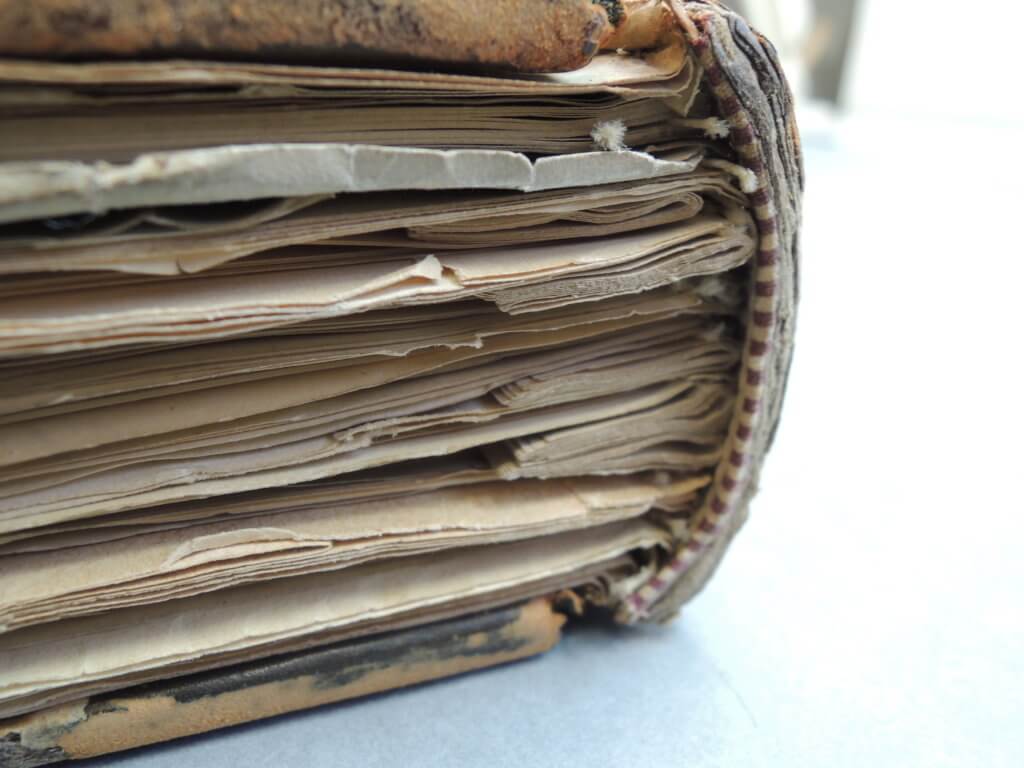

Figure 1: Miscellaneous Report volume structure showing typical features; stuck-on end bands, different document sizes and manuscript compensation guards. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The collection dates mainly from between 1850-1928: a time where the transportation, cultivation and commercialisation of useful plants was of critical importance to Imperial Britain, and to its colonial administrations around the world. While it gives us historical and scientific information about ‘useful’ plants and products, the Miscellaneous Reports also provide us with an important window into the work of Kew at this time.

Plants were sources of food, medicine, clothing, and construction materials. But above all, they were useful sources of money: it was vital to know what might successfully be grown and produced where, and whether this could provide a good source of income for and from a colony.

Kew was effectively the botanical arm of the British Government. It was a central player in coordinating the movement of seeds, plants and people around the world. They were part of complex global and colonial networks of government administrators, botanists, gardeners and foresters, commercial companies and individual traders, explorers, colonists, and sometimes just interested individuals and enthusiasts.

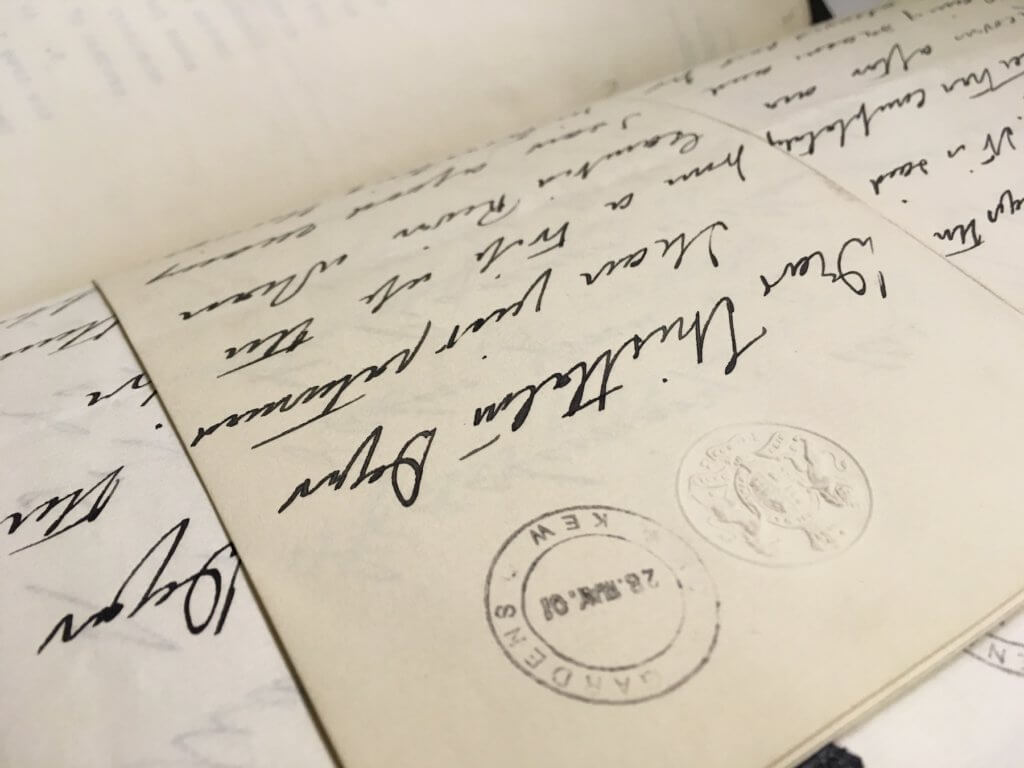

Figure 2: Open page of correspondence in the Miscellaneous Reports Collection. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Kew was actively gathering information as well as requesting specimens, adding to the Museum of Economic Botany and the Living Collection. In 1917, Sir David Prain, contemporary Director of Kew, wrote ‘ [Kew] has been throughout its history devoted to systematic effort to acquire all the information possible of the native vegetable products of every part of the world’.

The Miscellaneous Reports Collection is the result of all these interactions, of this ‘systematic effort’. Not only is it hugely varied, but it is also vast, covering an enormous range of subjects, from sugar cane disease in Barbados, forests in Sudan, and botanical exploration in Afghanistan.

While this archive has huge research potential, until recently, a significant barrier to accessing this important collection has been its uncatalogued and physically deteriorated state. Recognising the importance of the collection, and the risks of these barriers to access, in 2018 the Wellcome funded Miscellaneous Reports Project began, to catalogue the collection and undertake priority conservation work.

Caring for the Collection — Aimée (Project Conservator):

As you might imagine, I came into a conservation career from a love of history, heritage and science, so when I’m delivering a conservation treatment, I take care to think about the people involved in the story of the item; this sense of intimacy is even more profound when this takes the form of manuscript material; marginalia, notation and even doodles can reveal so much about the character of the author.

Unfortunately, some of the material has lasted better than others, which has meant more significant intervention was needed. Every type of item requires unique preservation considerations, but as part of the item history, they have all been altered to enable binding into a volume. As a rule, newspaper and other machine-made papers are generally the more damaged because they have short cellulose fibres with a higher acid content, meaning they degrade more readily and rapidly lose mechanical strength, leading to tears.

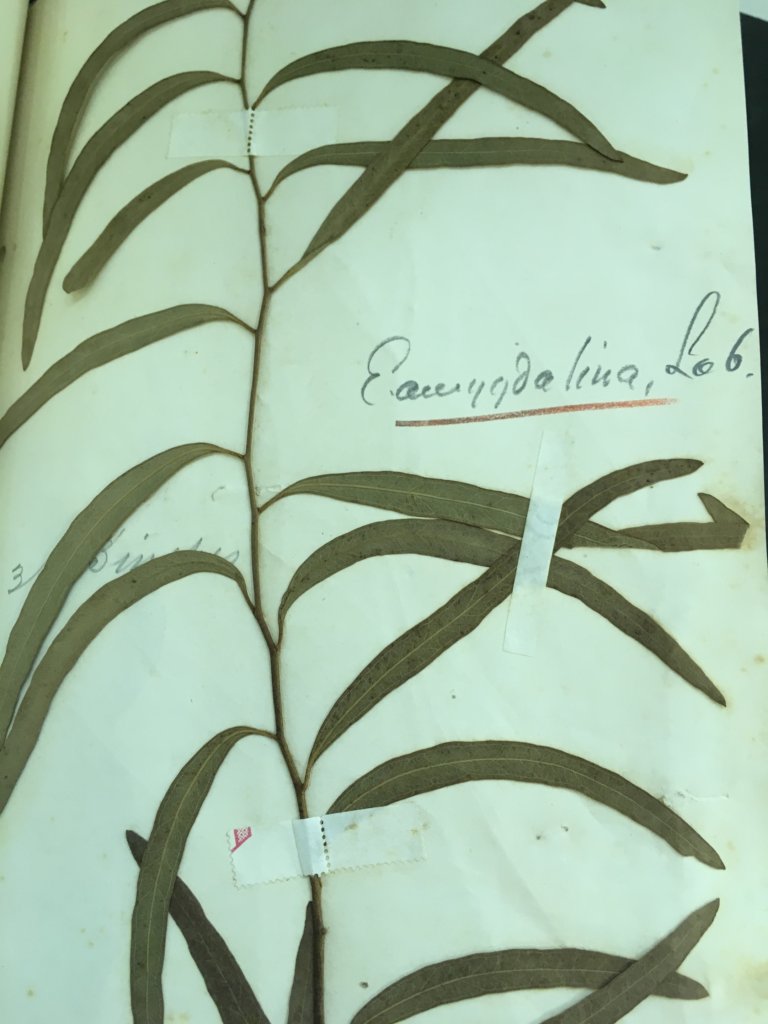

Figure 3: MCR/10/3/4 f.79, Dried Eucalyptus specimen from Miscellaneous Reports volume ‘West Tropical Africa: Eucalyptus’. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

As the material of the Miscellaneous Reports was originally produced as correspondence or other flat format types, the introduction of physical tension caused by the choice to bind the items into a volume has impacted the paper differently due to the differences in chemical composition. So, a 19th century manuscript letter on rag paper stock written in alkaline ink will typically have less damage than the material types previously mentioned because the cellulose content is higher, the ink isn’t acidic, and the fibre strength is more robust as consequence.

In some cases, to preserve the content of the volumes, the best choice was to disbind and return the paper documents to a flat format. This is a radical but essential change to ensure the stability of the content and all format changes involve rigorous documentation, so none of the data is lost.

Every treatment decision that I have taken was carefully considered to ensure that this historic archive of material will remain accessible for years to come.

Cataloguing and Accessing the Collection — Rachael (Project Archivist):

The Miscellaneous Reports Collection has been an incredibly rich, fascinating, and challenging archive to work with, exploring what’s behind its vague title. At 772 volumes, it is also huge, and made up of not only handwritten letters and reports, and printed documents, but also newspaper cuttings, photographs, maps, illustrations, and even plant and product specimens.

As an archivist, every collection you work with is unique and interesting in its own way, but the sheer scope and variety of the Miscellaneous Reports is amazing. I really didn’t know what I was going to find as I turned each page, from a sample of silkworm gut to a letter about the dangers of drinking too many cups of pu’erh tea. The volumes are arranged following a historical geographical classification system covering the globe, with emphasis on countries previously linked to or controlled by the British Empire.

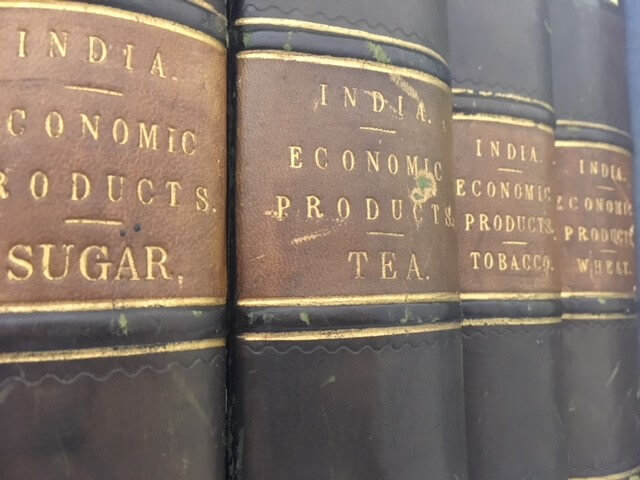

Figure 4: Volume spines of the Miscellaneous Reports Collection. Images are reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The archival remit of the Miscellaneous Reports Project, begun in 2018, was to catalogue the collection to file level, meaning creating a description for each of the 772 volumes, to increase its accessibility for a wide research and user community, and raise awareness of the value and potential of the collection.

For a researcher looking at this collection before the project, you would be able to navigate by geographical area, but would only have the title from the spine of the volume as a guide to its contents. And often, this would be something like ‘Egypt Miscellaneous’ which doesn’t convey the huge range of subjects covered within the volume, from cotton, diseases and pests, lettuce oil, mummy cloth, and ‘Moorghat’ [Moghat] and its medicinal uses. If you were interested in a particular plant or product, person or organisation, you wouldn’t have been able to search across the collection for this information.

During the project I described each volume to archival standards and this catalogue is now freely available.This transforms access to this material, and crucially helps users to travel across the collection in different ways and make connections across its vast global scope. Further indexing of subjects, names, and plants help make these connections.

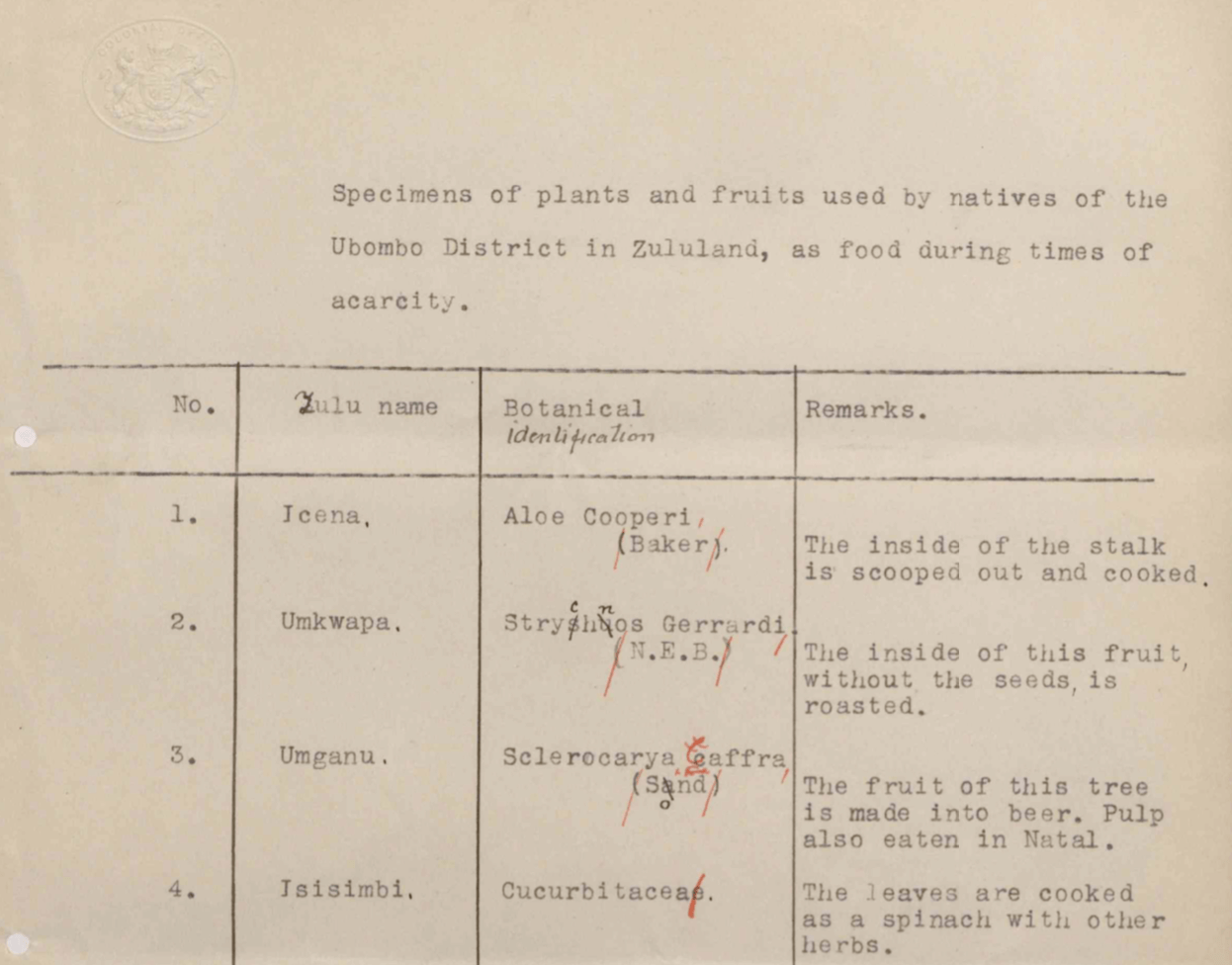

You cannot separate the Miscellaneous Reports Collection from the context in which it was created, which was the colonial project, and the control of natural resources and use of Indigenous plant knowledge. An example where this is really striking is in a document sent by the Governor of Natal (now the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa) to Kew in 1897. It follows a letter discussing a recent drought and locust attacks that had caused a state of scarcity in the Kingdom of Zululand. The Governor attributed the absence (as far as he knew) of deaths from starvation to the population of the Ubombo District’s knowledge of food plants. Here you can see a list of these food plants, with the Zulu name, its botanical identification, and remarks on how the plant was used (Figure 5).

Figure 5: MCR/12/3/4 f200, Document from Miscellaneous Reports volume ‘Natal: Miscellaneous’. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

This is an example of the very specific, granular kind of information about the use of plants by Indigenous communities that can be seen in the Miscellaneous Reports, which demonstrates just how much value was placed on Indigenous knowledge itself, not only on the collection of plant specimens. This is also a clear example of the problematic nature of that information exchange—the context in which this information was obtained, namely the unequal and exploitative power structures of colonial administration, and colonial control of natural resources.

Cataloguing this complex, colonial collection has raised many questions, from approaches to historical place names, offensive language, the absences and silences within the records, and treating the traces of Indigenous knowledge and histories respectfully.

This catalogue is a first step in improving accessibility and enabling further research, and being transparent about this part of Kew’s history. There remains so much more to do, and I encourage everyone to engage with this fascinating and challenging collection, to uncover more of its stories, and explore how it can support a wide range of research.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Aimée Crickmore is Project Conservator for the Miscellaneous Reports Collection at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew where she has worked as both Book and Paper Conservator. She is an ICON PACR Pathway member, and has conducted research on uncommon applications of Cyclododecane within the Conservation discipline, as well as other select polymers. Working at Royal Botanic Gardens Kew has sparked a love of botany which has led to her particular interest in herbarium and exsiccata.

Rachael Gardner is a Project Archivist at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Bringing experience of cataloguing 20th century, and 18th century archives, the Miscellaneous Reports Project took her into the 19th century and the world of economic botany. She has found working with such a varied colonial and scientific archive rewarding and challenging, and continues to explore new approaches to archive practice and the decolonisation of archives.

Published: 08/02/2021