From “know your place” to “reclaim your space”: the politics of participatory mapping

Trang LeMay 25, 2021 | Reflections

Soon after moving to Melbourne, I occasionally experienced incidents of street harassment. For the record, this is not to say Vietnam, where I had been living most of my life before, is in any way safer. Yet, the historical legacy of zoning here and the new reality that I’m now living beyond the public transport rich areas make me more vulnerable. In a feminist mood of feeling resented and waking up to the need for being more vigilant, I searched for some safety tips. Compared to the paternalistic advice I often got back home — ones that constantly reminded me to know my place — I’m surprised to find out about hundreds of apps and devices designed to prevent sexual violence, with an empowering overtone that asserts women’s right to the city.

Among these, digital participatory mapping stands out as a respectable initiative that builds on the ground-up, collective efforts and renders women as expert of space. It combines digital cartography with participatory methods, allowing women to communicate their experience of localities in real-time. It aims to raise awareness of the scale and severity of sexual violence, as well as assist women in making informed decisions should they wish to stroll the city. Conceptualising the risk of sexually assault as the by-product of the surrounding environment, perpetually present, yet determinable and manageable, these apps leverage participatory mapping as an apt solution to spatial inequality. But this conception of sexual violence and its corresponding mapping solution have far-reaching effects on women’s subjectivities, the spaces through which we move as well as our pursuit for justice.

Image caption: Heat map visualising the level of safety of a locality or place with the My Safetipin app| Pic: Safetipin

Wanting to stroll safely? Let’s manage the environment

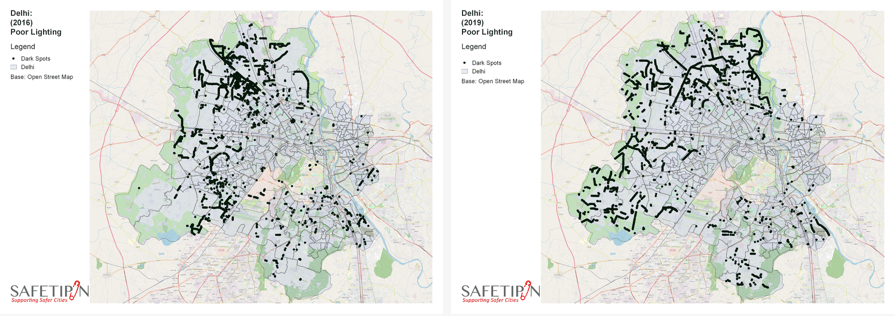

Describing the motivation behind the birth of a crowdsourced map called My Safetipin, its founder said: “the idea originated from the fear that women and girls experience before travelling to or through certain areas which were known to be unsafe for numerous reasons including bad street lighting”. Here, physical infrastructure — that is bad street lighting — is understood to be responsible for a woman’s perception of risk. The logic, then, implies that mapping “bad” places and giving them a safety score could serve to collect evidence, raise awareness, and lobby for improvement in urban design, which would bring safety to women as a result.

This is not a new logic, but a consistent characteristic of a “risk management framework” that displaced the notion of “dangerousness”, which has dominated rape prevention strategies since the 1980s. Whereas “dangerousness” stresses the importance of identifying and containing “risky” individuals, “risk management” focuses on comprehensive monitoring of a range of abstract factors deemed liable to produce risk. Differently put, attending to a dangerous person or an individual in danger is substituted by monitoring a host of risk factors and preemptively intervening in the physical settings that are thought to produce risk, such as improving road, install more lighting, or increasing the presence of police, before a risk could take place.

Sexual assault, then, is positioned as a prediscursive reality, a priori that precedes both the victims and the perpetrators. For example, in the policy brief “Technology as a tool to make cities safe and combat violence against women”, the United Nations refers to sexual violence against women in public spaces as an “underrecognised pandemic”. Similarly, media coverage portrays sexual assault on campus as an “epidemic no one is talking about”. All too often, sexual violence is framed semantically as a perpetual risk lingering in the external environment, a virus a woman might catch anytime. Meanwhile, the perpetrators are absolutely absent, their motivations are treated as purely opportunistic, and the power asymmetry underlying rape culture seems to dissipate into thin air.

This logic has not changed for past several decades, but the development of these digital maps should also be understood within the emergent imagination of the city as “calculative machine”. It reflects the contemporary enthusiasm surrounding the smart city and the deployment of data to manage the increasing complexity of the urban world. As the founder of Safe and the City puts it “we can only change what we can measure”.

But what is at stake when we fervently believe in digital mapping as a tool for empowerment? Does the map simply represent the physical space as it is?

Datafying risk, resignifying space

Accumulating and distilling a range of discrete personal accounts of space result in a smoothed out visualisation of a colour-coded map that communicates the seemingly objective risk of a locality through a safety score. But we must not forget the myth of the black rapists — that white women’s fear of sexual assault often serves to attack the freedoms of men of color. This geographical profiling, therefore, cannot attest to the fact that space is always in the process of transition as a result of continuous, dialectical negotiation of power among different actors.

Treating sexual assault as primarily a question of probability is, in the end, just another way to ignore that different groups gain control of space at different times, and that it is the social relations within space, rather than the inherent design of space that serves to exclude women. On a broader scale, geolocative data collected through these platforms are often relayed with other types of data, decoupling data flow from its origin and re-assembling them for different purposes. There is a very real possibility that local law enforcement can use the mapped reports to focus their policing efforts on particular neighborhoods, further criminalising them. Digital maps are, therefore, never a neutral means to represent spaces, but play an active role in changing meanings, resignifying territories, including certain groups, and excluding others.

Until we confront the culture of male privilege enabling sexual violence, until we acknowledge that sexual assault is not an opportunistic crime but a form of structural domination serving to exclude women and other minorities, intervening in the built environment or accesorising women with more tools and apps is just chasing feathers in the wind.

Trang Le is a PhD candidate at Monash’s School of Media, Film and Journalism, Australia. Her research project is situated at the intersection of technologies and gender, focusing on the politics of space and embodiment.

Published: 05/25/2021