I Can’t Breathe, Pollution, & Racial Justice

Vaibhavi ShahMay 3, 2021 | Reflections

Despite all of the changes during the pandemic, there has been one central consistency: a renewed focus on the air that we breathe. Around the world, the inherent right to breathe has become a focus of social, political, and technical debate. Instead of an invisible process, something instinctual, breathing has become a conscious action fraught with consequence.

This post explores the politics and perceptibility of breath during the COVID-19 pandemic as it relates to the intertwined history of environmental justice, the civil rights movement, and racial justice in the United States. Using an STS-centered approach, it connects how long-standing issues of pollution have contributed to racial inequities in health outcomes, leaving certain populations vulnerable to the pandemic. This discourse is related to the intersection of racial justice and breath with the tragic resurgence of the “I Can’t Breathe” movement after George Floyd’s death, highlighting social issues against a scientific backdrop.

Environmental Justice and Racial Equality

Due to the disproportionate impact of pollution on minorities, racial justice and environmental justice have been deeply intertwined throughout history. Former U.S. House Representative from Georgia, John Lewis, referred to the relationship of environmental justice and civil rights as a means to guarantee clean air as a “right of all, not a privilege for a few”.

The 1970 Clean Air Act helped establish national air quality standards, effectively limiting the amount of harmful pollutants in the air. Here, government action mitigated environmental damage due to industrialization over time, serving as a mandate to protect individuals irrespective of their background. Yet, the Clean Air Act made something factual and straightforward, the science surrounding pollution, an object to be regulated and swayed by political players. The readiness of politicians to deny clean air to minority communities reiterates the argument that Representative Lewis made that breath is a privilege.

Factory smokestack near Charlotte, North Carolina. Photo by Sam Sutharson/Unsplash.

According to a research study done at the University of California, Berkeley, Black Americans are 52% more likely to live in regions with high-risk pollutants. This inequity brings new meaning to the phrase “I Can’t Breathe” and gives rise to preexisting conditions that allow the COVID-19 pandemic to affect certain populations more than others. The invisible killer, SARS-CoV-2, joins other dangers in the air such as particulate matter from factories, leading to comorbidities that have been linked to poorer outcomes after contracting COVID-19. While the pandemic is an issue specific to this past year, vulnerabilities have been established for years with the silent, persistent poisoning of air pollutants.

The pandemic came as a shock to many who were distanced from the everyday effects of pollution, and had yet to see a blatant attack on one’s respiratory system like COVID-19. Yet for vulnerable populations in urban centers, COVID-19 is simply an extension of the longstanding attack on one’s right to breathe. “I Can’t Breathe” is an all too familiar phrase, as it relates to pollution and racial justice.

Fighting for Breath—George Floyd and Anti-Maskers

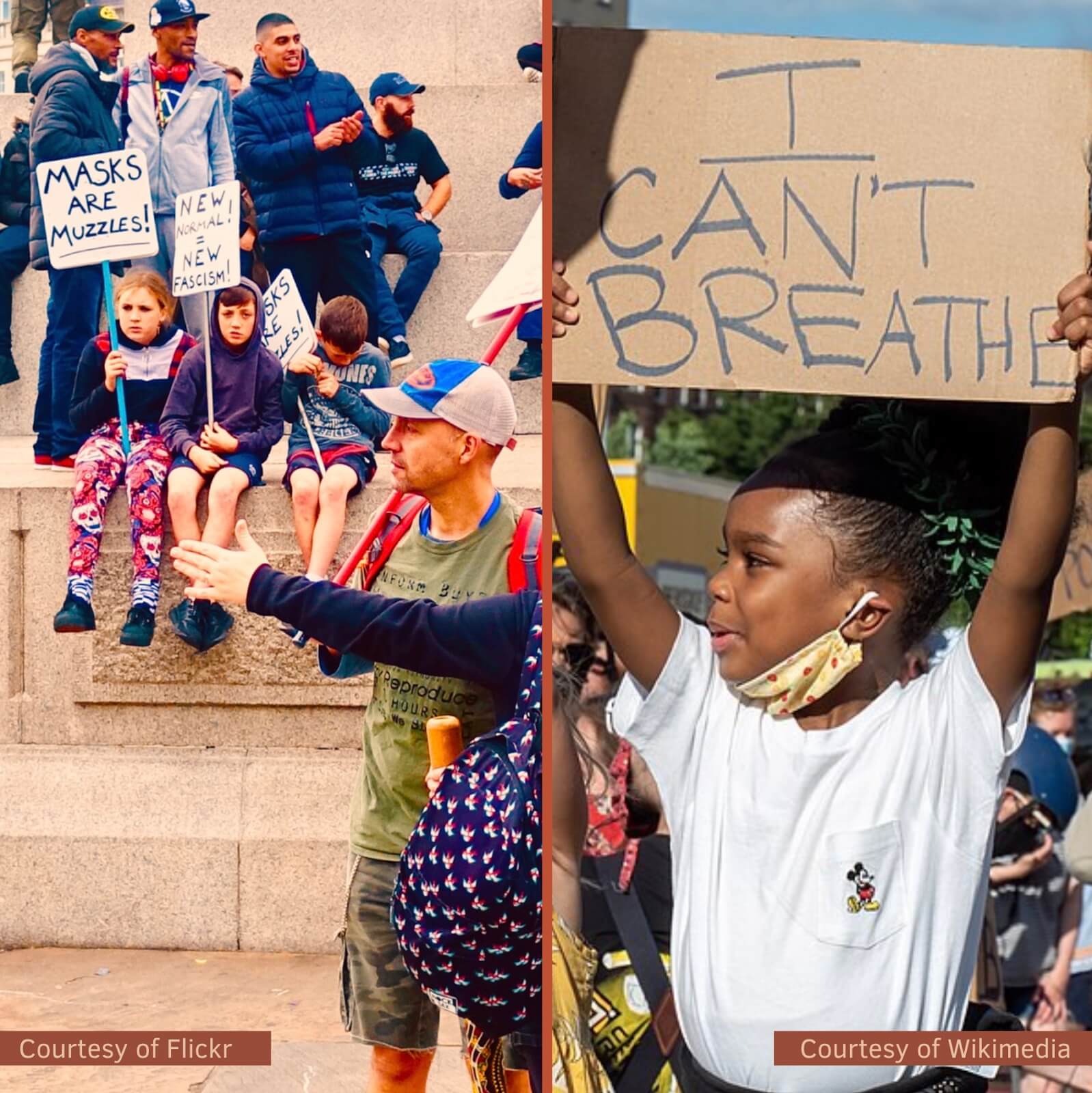

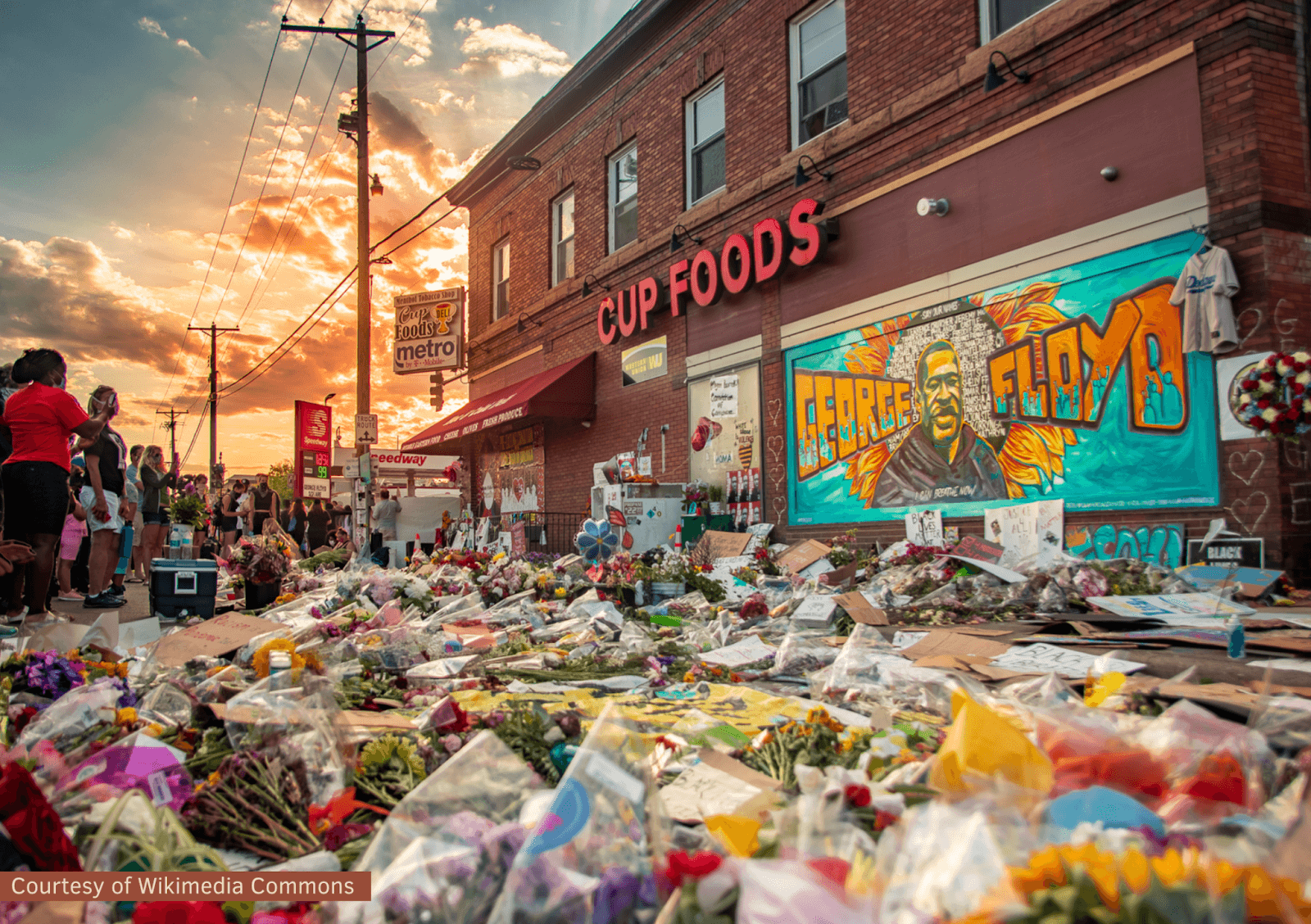

The never-ending attacks on breath brings us to the COVID-19 mask mandates and politicized arguments about our right to breathe. The buzz around wearing masks or social distancing—all to preserve breath—seems out of place when a person’s right to breathe was disregarded in the case of George Floyd. Floyd was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin, who placed his knee on Floyd’s neck until he could no longer breathe. Following Floyd’s death, the phrase “I Can’t Breathe” became the rallying cry of protests during the summer of 2020.

Calls for justice for Floyd were marked as political movements—an individual’s right to breathe, and not have this breath maliciously taken from them, was seen as political. With this political designation, protests were brushed aside along partisan lines, rather than taking it as it is: a fundamental violation of human rights.

Anti-maskers, the colloquial term for individuals who refuse to wear a mask, began to harness the phrase, “I Can’t Breathe”, to fight for their own right to breathe as they please. Influential council members, such as Guy Phillips of Arizona, compared the discomfort of wearing a mask to the inability to breathe in a counter-protest like manner to racial justice movements. This politicization stems from the inherent translation of mandated masks orders as an infringement on one’s freedom. Anti-maskers aligned themselves to movements that validated their feelings, from All Lives Matter to organizations by individuals in public office.

Phrases like “give me liberty or give me death” or “my body, my choice”, progressive messages for their time, were co-opted to describe the unwillingness to wear masks. This adaptation of historical phrases for a cause that directly violates public health guidelines shows a deep contrast in the nation regarding the access to air to breathe. The unwillingness to wear masks is an issue that is divided along partisan lines, with more Republicans expressing discomfort with mandates. This politicization jeopardizes lives, making “I Can’t Breathe” all too relevant when describing the effects of the pandemic.

Left: Anti-masker protestors (August 29, 2020). Photo by Gerry Popplestone/Flickr cropped to fit, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Right: Child protesting the death of George Floyd in Grand Army Plaza (June 7, 2020). Photo by Rhododendrites/Wikimedia Commons cropped to fit licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The ability to be in the position to take breath away is one enabled by political forces, as we see with all too common examples of police brutality. During the protests in Summer 2020, police forces threw tear gas into crowds, which can cause tightness of breath and irritation of the respiratory tract. Individuals participating in these protests were doing what they could to protect themselves from the other force taking away their breath in addition to the virus: tear gas. If tear gas coincides with a COVID-19 diagnosis, individuals can face heightened dangers since they might not be able to smell the tear gas and unknowingly inhale large quantities. Here, multiple agents restrict breath, from the initial chokehold on George Floyd to crowd-control weapons at protests.

The statement “I Can’t Breathe” has been used in the context of preserving one’s right to breathe across domains. With environmental justice, “I Can’t Breathe” is tied to the deterioration of air quality which disproportionately affects minorities. With protests against police brutality, “I Can’t Breathe” becomes increasingly relevant with the manner in which George Floyd was killed. And with mask wearing, the phrase was appropriated to fit the political leanings of those that felt the mandated masks restricted breath and freedom. The relevance of this phrase through history highlights the central role that breath plays and unifies different threads of political discourse.

Mural of George Floyd in Minnesota (June 5, 2020). Photo by Vasanth Rajkumar/Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vaibhavi Shah (@vaibhavibshah) attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 2017 to 2021 as a Bachelor’s student in Science, Technology, and Society and Biological Engineering. Vaibhavi has previously conducted research in big data in medicine, clinical neurosurgery, and the intersection of medicine and society. She intends to use this background to inform her future career as a surgeon-scientist.

Published: 05/03/2021