A Sociotechnical Exchange, Redux

Lucy SuchmanMarch 1, 2021 | Reflections

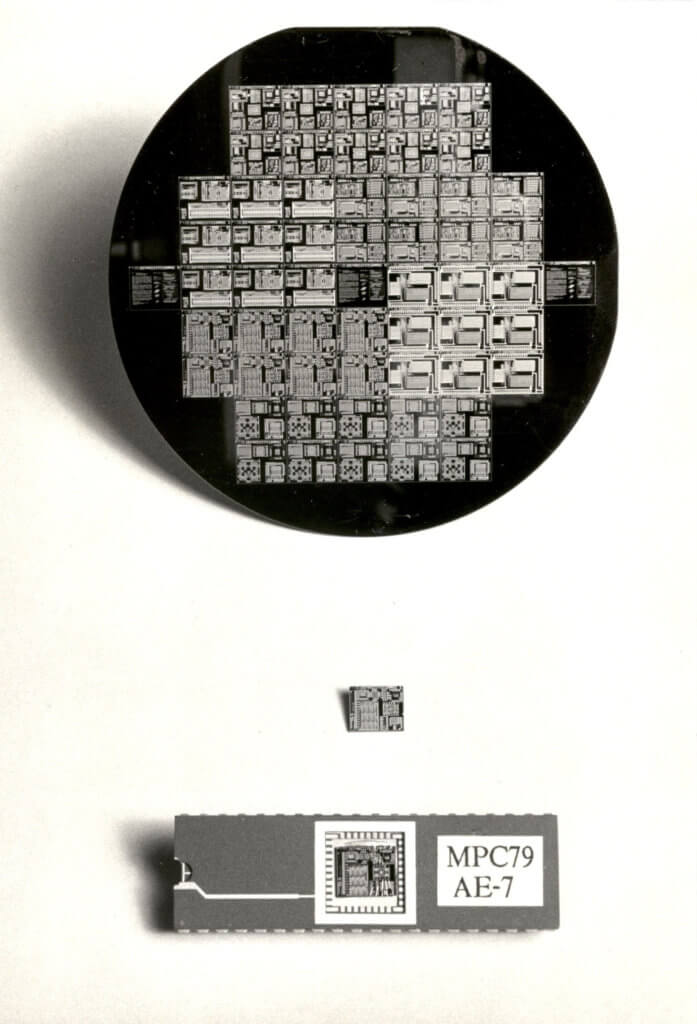

In 1980, at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), I entered into a rather extraordinary conversation with computer architect and electrical engineer Lynn Conway, then head of the LSI (Large-Scale Integration) Systems area. As a recently arrived research intern at PARC and PhD student in Anthropology at UC Berkeley, I was in the very early stages of formulating plans for my doctoral thesis. Lynn was emerging from a period of intensive activity focused on the ‘multi-university, multi-project chip-design demonstration’ (MPC79), an initiative involving the creation of a new pedagogy and associated design and manufacturing process for the production of very large-scale integrated circuits (VLSI). (For insights into the VLSI Revolution in silicon-chip architecture and design, in which MPC79 was embedded, see Conway 2012.) At Lynn’s suggestion, we entered into an exchange born out of her desire to think about what she had just experienced anthropologically, and mine to deepen my understanding of her sociotechnical imaginary and practice.

With Lynn’s endorsement, I recorded and transcribed our conversations, aided by an Alto computer and the text editor Bravo, both recently developed and in everyday use at PARC. The resulting text, which I printed out to share with Lynn and archived for myself in a 3-ring binder, was around 55 pages. Lynn and I lost touch over the years following our respective departures from PARC until, in 2020, another PhD student, Philipp Sander, contacted Lynn to interview her. Engaged in doctoral work in Media and Cultural Studies at Leuphana University in Germany, Philipp was interested in understanding the place of Lynn’s VLSI work in the history of the microchip, and in the course of their exchange, she pointed him to me as someone else he might talk with. Philipp’s consequent email sent me down to my basement to retrieve the binder and re-read the transcript. Most importantly, it reconnected me with Lynn, and our conversation resumed with as much enthusiasm as it had begun 40 years earlier.

- Lucy Suchman at the first Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work in 1986. (Photo by Ben Shneiderman)

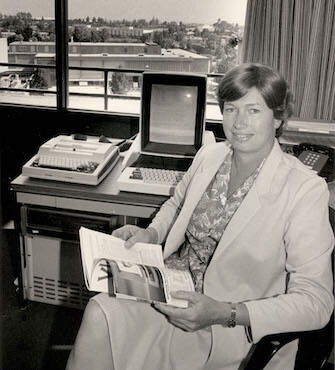

- Lynn Conway in her office at PARC in 1983. (Photo by Margaret Moulton)

This contribution aims to provide some context for the Conway-Suchman Conversation, to highlight just a few of the topics that emerge from it, and to reflect on the directions in which our conversations about that conversation are taking us as we, in Lynn’s words, “grope our way into ever-clearer mutual understandings of the events surrounding that earlier encounter.” As Lynn points out, rather than serving as any ‘real record’ of what we were thinking at the time, the transcript only just cracks open the door to shed light on what was going on in each of our worlds. For example, we have already noticed that rather profound social, political, and interpersonal forces were at play that were not only not discussed but were quite carefully kept between the lines of our text (for writings of each of ours that begin to elaborate some of that subtext see Conway 2011; Suchman, 2011, 2013; for insights into Lynn’s personal journey across what she names these techno-social space-times see Casal Moore 2014). It is those threads of the subtext that we are now most keen to recover, to trace their effects and their wider resonance with other (his)stories of technoscientific research and development.

The published text is the unaltered transcript of our original conversation. Making use of the features of the open-access platform PubPub, we’ve begun to add annotations in the form of comments; relevant sources as well as reflections on how we might now rephrase, reconsider, or question further things said. This is a living document for us, a contribution to the archive of one powerful moment in the history of computing, and a site for our ongoing discussions. We’ll continue to elaborate both its context and its subtext, through further links and references to come. For now, we’ll leave you with a few keywords from our conversation:

Interdisciplinarity

Our conversation is an occasion of thinking together across multiple disciplines, most obviously computer science, electrical engineering, anthropology/STS, and ethnomethodology. As such, it manifests instances of partial connections (see Haraway 1988; Strathern 2004; Verran 2013). While full of resonances, it is infused as well with moments where it becomes evident that our frames of reference are somewhat incommensurable – moments that we’ve begun to note in the annotations.

Labor and automation

Our conversation touches repeatedly on questions of automation, and more specifically the politics of labor that order automation projects, as well as on relations of normative descriptions/prescriptions to the in-situ practices that variously enact or resist them.

Demystification and democratization

For Lynn, MPC79 demonstrated a radical alternative to the restrictive economies and esoteric knowledge hierarchies of microchip design and fabrication that were dominant in the 1970s. The initiative included a new approach to teaching integrated circuit design, aimed at simplifying design principles and streamlining techniques for implementing designs as functioning microchips. The objective of this pedagogy was to greatly expand the range of technical practitioners capable of contributing to innovations in complex digital systems architecture. (See Lynn’s VLSI Archive Spreadsheet for more.)

Standards

Lynn’s story of MPC79 celebrates the power of standards (in design language and exchange protocols) to enable participation in the design process. Standards were key to the simplification of design methods and tools, as well as the practical logistics of design submission and chip fabrication.

Networked collaboration

Quite remarkably, Lynn’s account of MPC79 is also an account of one of the first cases of collaboration enabled by networked computing. At the time of our conversation, the Internet had not yet been configured; PARC shared the networked infrastructure of the ARPANET with just a handful of universities. Lynn experienced MPC79 as, in her word, a “network adventure,” and she understood the opening to collaboration and iterative design that the network afforded. Sociotechnical networks are central to this story.

MPC79 Wafer Type A, along with packaged and wire-bonded project-chip AE-7, January 2, 1980. (Photo courtesy of Lynn Conway)

It becomes clear in her story that Lynn is animated by an engineering ethos that searches for mechanisms, which once identified and understood enable interventions and efficiencies. She hunts for what she sees as the underlying simplicity upon which (even baroque) complexity is built. And she is unapologetically entrepreneurial. My anthropological sensibilities, in contrast, make me wary of machine metaphors and projects of social engineering, while poststructural thinking in the social sciences takes the imaginary of underlying foundations itself as a topic, and favors more genealogical analysis. At the same time, Lynn has read across an extraordinary breadth of both natural and social scientific literatures in a lifelong project of, in her words, the “Scaffolding of Investigative Dimensionalities and Portals for Exploring, Mapping, Modeling, Simulation and Launching of Techno-social Dynamical-Systems in Evolutionary Space Time”! (To see more of the imaginary of techno-social evolution in which Lynn operates, see her 2015 Steinmetz Memorial Lecture.) Lynn appreciates deeply the agencies of artifacts, and the dynamics and temporalities of human (and more-than-human) transformation.

Lucy Suchman is Professor Emerita of the Anthropology of Science and Technology at Lancaster University in the UK. Before taking up that post she was a Principal Scientist at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), where she spent twenty years as a researcher. Her current research extends her longstanding critical engagement with the fields of artificial intelligence and human-computer interaction to the domain of contemporary anti/militarism. She served as President of 4S from 2016-2017.

Published: 03/01/2021