Krea University, Its Interwoven Model and the Implications for the Study of History

John MathewFebruary 15, 2021 | Reflections

Were a calendar year to assume the guise of a nation-state, I wonder how many of us would clamour for citizenship within the legal borders of 2020. In the face of such staggering losses of life and livelihood as we have countenanced, how do areas of professional occupation that are already precarious endure? It is to the academy that such questions are most searchingly posed, particularly to disciplines whose salience has frequently been questioned. This has been true of the history of science, a fugitive subject at best in so many places where it may be found, lurking uneasily within the context of a larger history department, or allied to another subject, say medicine for those of the discipline who perform the kind of research that health practitioners may recognise. It is against this double hamstringing that I present what the pandemic poses for an institution on the make, the one where I teach, Krea University in Sri City, a remote township that doubles as a Special Economic Zone in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh.

Academic Building – Krea University – Photo by author

Krea,whose location is owed to the self-contained, self-sustaining campus of the former Institute of Financial Management and Research (IFMR), which recently folded into the new entity as its Graduate School of Business, is an early entrant into the realm of the private university in India and is accredited under the Andhra Pradesh Private Universities Act. An inspiration, if not complete model, is Ashoka University in Sonepat, Haryana, in the north of the country. Like Ashoka, Krea does not depend on a single donor in whose name universities are often founded (O. P. Jindal, Shiv Nadar and Azim Premji universities are examples). There is a Governing Council, peopled by leading industrialists, an Academic Council with a redoubtable slate of names, and a slew of eager, promising young academics as pedagogues, with a peppering of a more grizzled flock. The emphasis is on ‘interwoven learning’, where disciplinary borders are meant to be porous; in fact, there are no departments, just larger divisions, three in number – Science, Literature and the Arts, and the Humanities and Social Sciences. Considerable thought has underpinned the development of the curricula for each of the subjects within the divisions with external reviews included. My own situation, having trained in ecology and the history of science at doctoral levels, equips me to teach in history, biology and environmental studies. Hence, in the first trimester of the majors (i.e. the second year), I co-led ‘Past, Present and Predicted Environments’ for Environmental Studies, and ‘Life at Different Scales’ for the Biological Sciences, and in the second term, I am in charge of ‘Environmental History’, which is cross-listed between Environmental Studies and History.

Amphitheatre – Krea University, Photo by author

Our first batch of undergraduate students for the School of Interwoven Arts and Sciences arrived in August 2019, and after the fanfare of a week-long orientation, entered a first year where a series of eleven mandatory courses, both core and skill, became their passport to the majors they hoped to pursue in their second and third years. To counteract the risk of being left withtoo little time to specialise, the university follows a three-term, rather than a two-semester system. The founding faculty (about 30 in number) was in place about half a year in advance of the arrival of the students, so as to develop the curricula for both the interwoven first year and for the majors, keeping in mind the delicate balancing act that requires negotiation between the freedom to choose among courses and the rigour demanded in any particular discipline.

Stairwell in Academic Building – Krea University – Photo by author

During the first year, students are greeted with lectures delineating the contours of the majors that they might pursue. History is of course among them, with an equal emphasis on both global and local (as in subcontinental) angles. The history of science gets some airtime because of a persuasive case made by the Divisional Chair of the Humanities and Social Sciences (himself a historian) for the inclusion of climate change as a key and necessary component of the larger curriculum for history, and likewise the related if contested provisional geological epoch, the Anthropocene. However, for a major in which there are six associated instructors, the number of students opting to read history as a degree has proven to be zero, with four students considering it for a minor. History has now been linked with politics (another subject with relatively few takers) to form a joint major, so that with the benefit of combined numbers, both subjects might, so to speak, make, if with some level of compromise. It is unlikely that the pandemic has much to do with this state of affairs. History has been hurting in many institutions worldwide and those of us practising it and refusing to see the implications of such a parlous state of affairs do so at our peril.

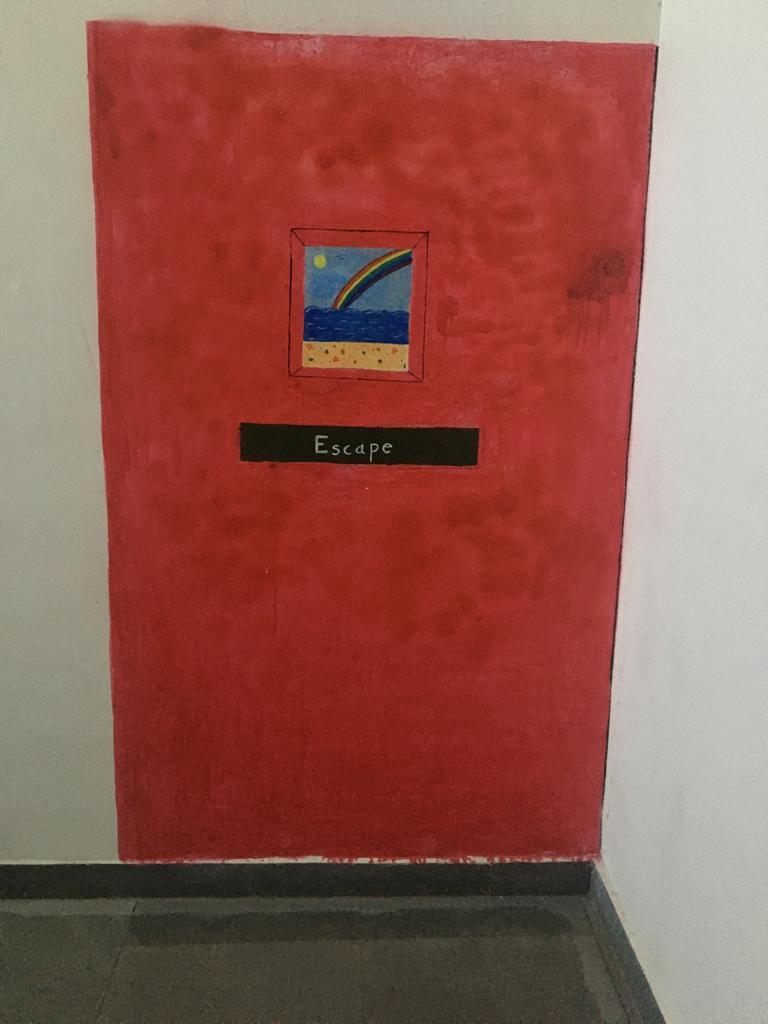

Play on Emergency Exit in Academic Building – Krea University – Photo by author

What the pandemic has produced is a metaphorical razor that seeks in its depilating wake to provide startling clarity, tethered to the utilitarian goal of a steady income through gainful employment. Krea students are complaining why fees are so dear when they are sitting at homeAt a moment where we are scrambling to understand how to teach online, where the learning curve is an abruptly sharp exponential, Krea can feel hard done by in that the monarch of all pandemics in a century happened to strike in the first year of its existence. Yet that crippling blow apart, the uncertainty of how to cope when the choice of majors is so lopsided (economics accounts for a third of our first batch, and four other disciplines, psychology, computer science, biology and mathematics, account for another third) is real. But even as student demand stays uneven, and staffing gets compromised for want of incoming financial resource, the question of how a subject like history can ride the storm becomes increasingly fraught. Within it, the history of science hangs grimly on by a thread.

__________________________________________________________________________________

John Mathew is an ecologist and a historian of science at Krea University, Sri City, Andhra Pradesh, India. His monograph, To Fashion a Fauna for British India, is currently under revision for Oxford University Press, India.

Published: 02/15/2021