EthnoData: A collaborative project in cross-disciplinary experimentation

Kaleidos Collective*January 18, 2021 | Projects

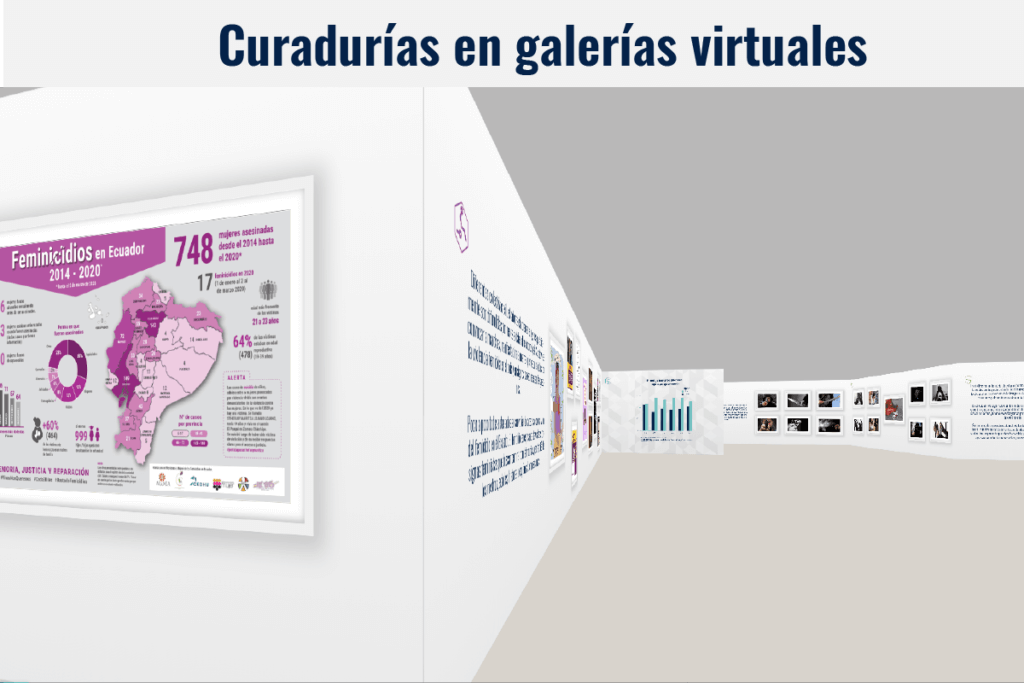

During 2020, Kaleidos built a new collaborative digital platform called EthnoData. It is a multimodal and multimedia website that combines large datasets with ethnographic material that allows users to create their own theorizations and stories through a variety of numerical evidence and qualitative data —including official statistics, legal archives, curated images, essays, videos, podcast, and other forms of ethnographic material. It currently focuses on violent deaths, hate crimes, femicides and missing people. Inspired by other experimental and collaborative digital tools like PECE, EthnoData aims at challenging and critically reflecting on the ways in which we design, share, organize, select, access, produce, communicate, and collaborate in digital spaces that accumulate vast amounts of information. As Lindsay Poirier (2017: 72) put it, we seek to “intervene in status quo design, establishing opportunities for surprise that trigger reflection.”

EthnoData was originally conceived to understand why violent deaths decreased in Ecuador over the past decade. The platform offers alternative hypotheses to the enforcement of punitive strategies. More broadly, the platform was developed so that users would be able to contrast information and produce multiple interpretations and considerations based on official statistics but also on various ethnographic materials. We highlight the way in which “ethnography, like other technologies can also be designed to challenge and change existing order, provoking new orderings of subjectivity, society, and culture” (Fortun 2012: 450). Two examples are femicides and hate crimes. Although Ecuadorian law recognizes them as specific kinds of crimes, in practice, they are often unregistered in official statistics due to the difficulty in proving the legal technicalities that differentiate them from other categories of violent deaths such as homicides. What this means is that police, prosecutors, and judges are often more inclined to present their legal cases within wider definitions of murder due to the legal complexity of proving a femicide. Ethnodata complicates numbers by providing additional ethnographic material that will situate data in the context in which they are produced.

We understand this as an experiment in Digital Humanities that challenges rigid disciplinary boundaries prevalent in our academic contexts. The idea of a hybrid analysis between, on the one hand, large datasets, statistics, and official figures and, on the other, an ethnographic story of those numbers is one of the greatest advantages of an STS approach. In this sense, we see EthnoData as a situated form of knowledge that interrogates how social sciences and computer sciences are done and interact in Ecuador.

One of the first conversation that guided the construction of EthnoData was Poirier’s (2017) invitation to be “devious” in our designing practice when she said that, “Designing critically should involve accounting for and disrupting the logics that are pre-embedded in the infrastructures available to designers […] devious design [is]—a practice where designers not only “make do” with the infrastructure available, but also leverage that infrastructure in ways that challenge its underlying logics”. Yet we quickly realized that in our context “devious” might have to be negotiated in specific kinds of ways—not all frictionless. Here’s an example. For months we tried to build a basic front-end interface for our site but often ran into discussions that confronted design, functionality, and analysis as they were imagined by communicators, engineers, and anthropologists. Eventually we decided to buy a pre-designed, responsive, and customizable template from an open-source web design company because we could not devote more resources (time or money) to this “menial” decision. It was a working solution, but one that illustrates what sorts of research is possible under our local, situated, defunded conditions.

The collaborations behind EthnoData have been an exercise in discovering the limits of our own disciplinary possibilities. What does anthropology resist quantifying? How can engineering rethink “mathematical neutrality”? How to move beyond econometrics’ contempt for ethnographic stories, and anthropology’s contempt for econometric “simplicities”? How can we complicate the idea of “neutrality” so endeared by hard scientists? How can we build bridges that allow us to “understand” each other, question and think beyond what we already know? These are some of the theoretical challenges that STS can approach to, and they are at the core of EthnoData.

A second level of complexity within the platform is to overcome systemic data distrust within Ecuador. Different government agencies have provided us with large datasets on violent deaths, yet civil society organizations challenge the very production of that data. In parallel many civil society organizations have also produced alternative datasets that are now included in EthnoData, however some government organizations also question this data because they argue it has been produced to represent their “ideological” views of, for example, femicides. The challenge for EthnoData is to design digital spaces that allow for previously incommensurable data to become analyzable in different contexts and by contrasting actors.

EthnoData is an experiment in conceptualizing and depicting critical data stories, but it is also a digital space “in the making.” The platform is inspired in STS debates in “critical making” (Ratto 2011) and joins other authors in proposing a “material intervention” in academic debates but also beyond these boundaries by “build(in)g alternative forms of technoscience” (Tirrell et al 2020). In that sense we are creating a space meant for users we do not necessarily already know. Our hope is EthnoData will generate a digital space for debate as well as continue to shape and be shaped by critical data studies. We invite to 4S community to explore, experiment, and probe what EthnoData is (and is not) able to do at this stage. We hope it will turn into a collective instrument that can help share knowledge as well as make data, interpretations towards more just, diverse, democratic, and equitable understandings.

Published: 01/18/2021