Why Feminist Figurations Matter in Energy Futures

Amanda Windle in conversation with Laura Watts and the Electric Nemesis

December 10, 2019 | Reviews

An encounter with the ethnographer of futures Laura Watts and the Electric Nemesis in a haunting review of “Energy at the End of the World: An Orkney Islands Saga”, 2019.

Writing With Fictional Figures

I got to deepen my encounter with the book entitled “Energy at the End of the World: An Orkney Islands Saga” (2019) by interviewing the author, academic and feminist STS scholar, Laura Watts (LW), and the main figure of the book, the Electric Nemesis (EN).

Image shows the front cover jacket of the reviewed book by Laura Watts and shows several layers of waves coming towards a shore and over large rocks. The photograph is entitled “Bay of Skaill” and is by the photographer Neil Ford.

Stories from the Orkney energy islands are retold as a saga in three parts, across many short sections that effortlessly flow for the reader. As Watts suggests,

LW: The book is written as an entire narrative arc… Many reviews treat the book as a relatively normative account of renewable energy infrastructure in Orkney, and they have been extremely positive about the sagas. So the book is travelling through the reviews and the reviewers. But it’s not the whole book.

The book can be read by academics and non-academics alike, for those interested in an array of topics, yet in this review it is the poetic mode of writing that matters.

LW: I’ve explicitly written the book with careful attention to language, to reach a wide diversity of readers. Written in narrative style, it’s quite lyrical. This helps the book to travel, that is— it helps Orkney and the Electric Nemesis to travel. If you do the job right as an author then people just take it in… my writing style aims to be invisible.

The book “flows” for multifarious readers even when the main figure in the book isn’t exactly easy to get along with, and purposefully so. The storytelling is entangled in a chilling companionship with the figure of the Electric Nemesis.

LW: The Electric Nemesis comes out of the Orkney landscape, from its Norse mythology, the Vikings and the Orkneyinga Saga. She blurs the lines between place and myth – their liveliness. She does work in words, when the words are well-crafted. She lives in a poetic space, in the interstices between words – she inhabits that space between words, where we feel. It’s where poetry and fiction do their work, and some academics do, too. Whilst I’m discussing energy infrastructures in the book, you can’t do the place and its landscape justice without this lyricism… So the figure of the Electric Nemesis, having a mythic aspect, is a response to a place that has these qualities embedded in it.

How did you go about writing the Electric Nemesis?

LW: When you’re writing you’re, in essence, mining for story and concepts. You’re mining through the obvious, the initial thoughts, and you have to keep chipping away. You’re looking for veins, for relations that sparkle. We don’t talk about the sheer amount of work it takes to mine the good stuff–to reach the rich veins. The Electric Nemesis comes out of that persistence. I had to find her. I found a rich vein of ideas and wrote many encounters with her, following her, learning about her. Only some of these were then needed in the book. Doing the hard graft of writing drafts and finding the Electric Nemesis was important. I needed a figure, but I had to write her into being through rewrites and edits, through putting the time in and doing the hours in her company.

How did you work with the Electric Nemesis?

The Electric Nemesis is a figure who engages with me as an ethnographer through the book. You learn more about her through the pages. Finding out who she is and why she is important is part of the story of the book. She is a figure that helps me to engage with the classic question of ethnographers: how do you make research travel, particularly in a location that is considered by some as remote and unique? If you do work in London or a large city it’s often considered more universal, more applicable to elsewhere, but not in more rural locations.

In the book, the Electric Nemesis helped me to bear witness to electricity and renewable energy in Orkney, so I’ve been drawn to focusing on her in this interview. I was surprised to learn that other book reviewers had omitted the Electric Nemesis, which I think misses the point of the book i.e. her role in the energy sagas, and how we might talk further about energy futures and climate beyond the usual frustrations and hype.

When I gave a talk at the Edinburgh International Book Festival (in the New York Times’ debate on climate solutions), questions from the audience were along the lines of: what should I do? The book is about why that is not the best question. The book is about what can you do where you are, with whom and with what you have to work with. The book is not there to tell you or anyone else what to do. It’s about asking a different question: who are you in this with? And what can you do together with your ‘oddkin’?

Meeting the Electric Nemesis

I had questions for the Electric Nemesis and the author, so I extended an invitation for an interview with both. I got the chance to speak to the Electric Nemesis after speaking to Laura Watts. There was a careful pause, a moment of preparation to find her voice, and I was then talking to the Electric Nemesis.

EN: I think you need to meet me, which means that I have to walk up your street… walk up to your door, and walk into your room, perhaps travel through an electrical socket or cable, and plug in. I might need some extra skin to materialise. My skin is thin… You’re thinking of me as one thing, a single figure, as though I have a beginning, a middle, and a singular end – but I am many.

We talked a while longer, but not for long because the Electric Nemesis doesn’t hang around and isn’t likely to be put at ease by an interviewer – if her presence in the book is anything to go by – to be haunted isn’t to feel at ease. The Electric Nemesis draws closer to me with her words, sniffing out any “bigsy” (the Orcadian word for hubris) in my line of questioning.

EN: I think the author will be haunted by me for some time. I think your job is to be open to be haunted by me, too. Can you write your review in that way? Can you allow me to haunt the words you write? Electricity is ethereal and haunting. We are speaking through electricity now. I am reaching through to you.

What’s it like, all that light on your skin? If I press my face to the screen does it push through to yours? If I breathe on the screen can you smell my dank breath? You can, if you write it. We’re tied through the power of the grid, through connection. I’m here. And I’m there, with you.

The Electric Nemesis and her miasma enables readers to understand the transitions that the author is bearing witness to, through her many relational encounters that involve renewable energy storage, transition, transfer (i.e. carrying) and use. How local wind, wave, solar, and tide electricity from the islands is carried to central Scotland by a single cable under the sea matters. There is an abundance of energy in the landscape, which is powering renewable electricity (120% of the islands’ electricity needs are generated from renewables) but it is being limited, curtailed, due to the carrying constraints of the cable infrastructure. Here, the abundance of renewable energy is a problem.

Bruck Innovation

Watts carefully details the carrying limitations of the single cable connecting Orkney to the rest of the UK. The islanders are reliant on the cable because it’s the only connection they have to carry their ‘Orkney electrons’ back to the National Grid. If the UK aims (via the Orkney-based, European Marine Energy Centre) to be at the cutting edge of wave and tidal innovation, the cable matters. There is also a reliance on global investment and venture capital for wave and tidal energy futures, as there is with hydrogen storage. Various collaborative business models are described in the book through stories, each illustrating the hype cycle, and innovating in short, repeated timeframes with significant underinvestment. Even while budgets falter, the Orkney energy sagas become positively affected and the story excitedly picks up narrative pace. When development scales back what continues are workable energy futures made at a local level, through collaborative practices of utilising “bruck”. It’s an Orcadian word for re-using materials, making do with what’s around, whatever you can find nearby, like repurposing an old refrigerated container in a field as part of making an anaerobic biodigester.

Bruck is brought together by “oddkin”. Watts builds on the term “oddkin” drawing on the writing of feminist STS scholar, Donna Haraway, so as to illustrate how island folk work together even when they differ, or are divided (see Haraway, 2017). They often work together against the logic of the free market, because the long term survival of businesses and therefore the islands depend on collaboration to survive (2019, 202). The Electric Nemesis is another kind of oddkin: she is more the readers’ oddkin.

EN: I’m put together from what folk find nearby. So what do you want to put into me? Are you willing to become part of me? Let me be a part of you?

Between Worlds

To become haunted by the Electric Nemesis, is to experience a shift in attention. The Electric Nemesis doesn’t seek out the readers’ attention, but rather the reader has to attend to her focus, timbre (psychoacoustics) and atmospheric presence (being-in-the-landscape). Particularly through the Electric Nemesis, Watts stays with the boredom of energy innovation by attending to words from otherly worlds.

LW: The other aspect of the Electric Nemesis, is a long-term relationship to innovation, inspired by Lucy Suchman’s work on innovation. It is a kind of long-term boredom with much of what goes by that monika. How do we relocate innovation, and what does it look like in different places. How can we re-conceptualise innovation? I needed a toolkit, a way to talk about Orkney innovation.

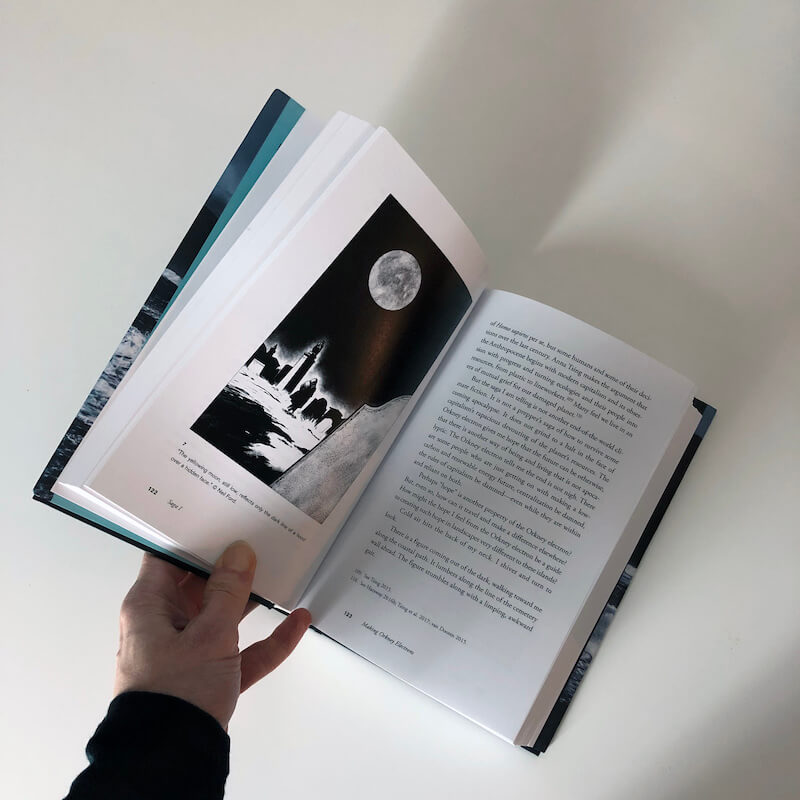

The toolkit also includes photography and illustration. While they both shape the book’s composition it is perhaps the photography that does more of the shaping. I noticed that the photographic images are altogether remiss of people. The Electric Nemesis is the only figure in the book that’s illustrated. The illustrator Neil Ford captures the metallic features, but it is the words that evoke her smell and sense-making; her crackling voice, broken body, and pungent presence.

The image shows an open page of the reviewed book by Laura Watts, held open at a page 26 of the book. The colour photograph shows Peedie ways through Stromness, a narrow paved pathway between stone buildings of Manse Lane, Stromness and is credited to Laura Watts.

The image shows an open page of the reviewed book by Laura Watts, held open by a hand showing page 122 of the book. The illustration shows an illustration by Neil Ford which is captioned, “The yellowing moon, still low, reflects only the dark line of a hood over a hidden face.”

The scenic photography with their respective photographic essays are thoughtfully curated and carefully staged within the book. I would like to say more, but I grew up around stone circles in England, and their resonance was said to haunt photography; either people disappear from the photographic negative or from life thereafter. I’m indulging this superstition by omitting the part of the interview where we discuss stone circles through photography.

LW: Thank you for saying the photographs are well-chosen. It was a long process because Orkney is a photogenic place. The light in Orkney is very reflective, which attracts a lot of artists and photographers. I have worked with professional photographers and there are several photographic essays in the book. I wanted a different way for the Orkney landscape to speak, but I’m not saying that photographs are unmediated … Photographs are central to what I do, and I knew I wanted to include photographs that speak for themselves rather than use them as illustrations.

The energy islands are remote and the photographs emphasise this with their stillness and attention to humanity through objects and buildings remiss of figures. This absence emphasises the reader’s attention to energy innovation through the character of the Electric Nemesis and her uncanny companionship with the author and reader. It is up to the reader to breathe the Electric Nemesis in, because only then might the reader be haunted by Orkney and its energy futures.

LW: For me as an author-ethnographer, the Electric Nemesis is about the visceral and emotional, uncanny argument.

Watts understands ethnographically why feminist figures and their figurations matter.

LW: The Electric Nemesis is not interested in just a cool academic argument. She wants what people feel–as an inseparable part of an ethnographic argument. People do have an emotional relationship to energy and that’s important in Orkney–the gale force winds, the community wind turbine, can be a passion, a frustration…

I’m not studying women or gender but I’m looking at power (in a double sense) and privilege. I explicitly wrote the book to be able to push conceptual, theoretical work in feminist STS, and for those interested in energy futures. I wanted to bring STS to a wider audience engaged with energy and electricity. I’m smuggling in Haraway to the energy industry.

Over the years I’ve discovered that many of those in renewable energy in Orkney, they get Haraway, they understand situated knowledge in their bones, understand issues around multiplicity–they experience the politics in knowledge and technology made elsewhere, imagined for places very different to their own in the islands. These things exist. It’s not theory we make up. It’s actual everyday experience and struggle, and our framing, our articulation, is enormously helpful–makes a difference.

The sagas could have been a grandiose ethnographic epic, given that there’s a decade’s worth of ethnographic research behind the book. However, I was left contemplating how the book captures energy as the scenic sublime, and does so with intimacy. It is through the Electric Nemesis that this can be fully appreciated. However, Watts goes one step further with a call-to-action.

LW: The book is written as a manual, and it’s hard to give you a quick start guide. You have to read the book to understand the Electric Nemesis and go on the journey with her. The book is intended to do that work. There’s no shortcut. But she’s intended to be open access and open source as a figure. I very much encourage people to write Electric Nemesis fanfiction, and see what she looks like in their world. She can sail over seas and up rivers and appear in unusual places, wherever a reader finds themselves. I’d like to hear back from the many different Electric Nemesis’ out and about in the world.

I’d like to hear from readers if they find the Electric Nemesis engaging. She is essential to the book and to me. She is her own diffraction. It is interesting that, so far, reviewers have not been willing to talk about her. To what extent have people engaged with her, I wonder.

Backchannels accepts alternative short form writing and can publish fanfiction for an STS readership.

Laura Watts is an ethnographer of futures, writer, poet, and Senior Lecturer in Energy and Society, Geography & the Lived Environment, at University of Edinburgh. As a Science and Technology Studies scholar, her research and writing is concerned with the effect of “edge” landscapes on how the future is imagined and made, and could be otherwise. For the past decade she has been working with people and places around energy futures in Orkney islands, Scotland. More on her work can be found at sand14.com

References

For all the reviews published about the book so far see the long list at the end of this page: https://sand14.com/energy-at-the-end-of-the-world/

Watts, Laura, Energy at the End of the World: An Orkney Islands Saga, MIT Press, 2019.

Published: 12/10/2019