The world in a billion points: Interview with ScanLAB Projects

Gökçe Önal

March 13, 2023 | Reflections

This week we feature ScanLAB Projects, a UK-based creative practice specialised in large-scale 3D scanning. Founded in 2010, ScanLAB collaborates with architects, broadcasters, scientists and artists in digitising places and events, working across multiple scales from those of objects and rooms to cities and landscapes. Using LIDAR scanners — a tool that emits light beams of a particular wavelength to construct a point cloud model of the targeted space — ScanLAB designs online environments, immersive installations and objects. The team maintains an interdisciplinary expertise as they operate from concept, through on location scanning, to delivered product. Over the years, their work has featured at various platforms including TV (docu)series, exhibitions, online museum collections and VR journalism, among others.

William Trossell, architect and ScanLAB co-founder, elaborates on the studio’s collaborations with scientific communities, the extents of the tool and potentials for future practice.

Your work involves collaborations with artists, museums, broadcasters, scientists and private companies, among others. In these collaborations, the spatial information you provide builds on other fields’ findings and expertise, often resulting in the production of new knowledge, evidence or stories. How do you manage the communication of your data across such diverse parties and disciplines? And how are different methods, techniques and scales (of measurement) merged in the process?

As humans, communicating through and navigating space are basic instincts, and our work tends to draw upon lots of conventions and magic within this language. We’re also informed by our background as designers, where we’ve honed our ability to take mathematics, data and stories, and turn them into visuals. As designers, our creative ambition — whether that’s through a sketch, a photo, or a render — is to tell theories through space.

We also don’t see laser scanning as just a measurement device. The scanner is also a camera, so a lot of our visual language and creative practice is based on photography, cinema and visual effects. We really enjoy that cross-pollination between different disciplines; each has an incredible story-telling workflow that has been designed and honed over the years, and we draw on those concepts to create our own work.

As you describe in a previous interview, your collaborations are often twofold in nature – engaging with the scanner as both ‘an “objective” measurement’ and a ‘subjective imaging device’. This is of course very telling given your particular stance between scientific and artistic production. In this regard, how would you recount your exchange with scientists as a creative practice? How do you think your involvement – as architects/designers/makers/coders – affects the process of scientific research?

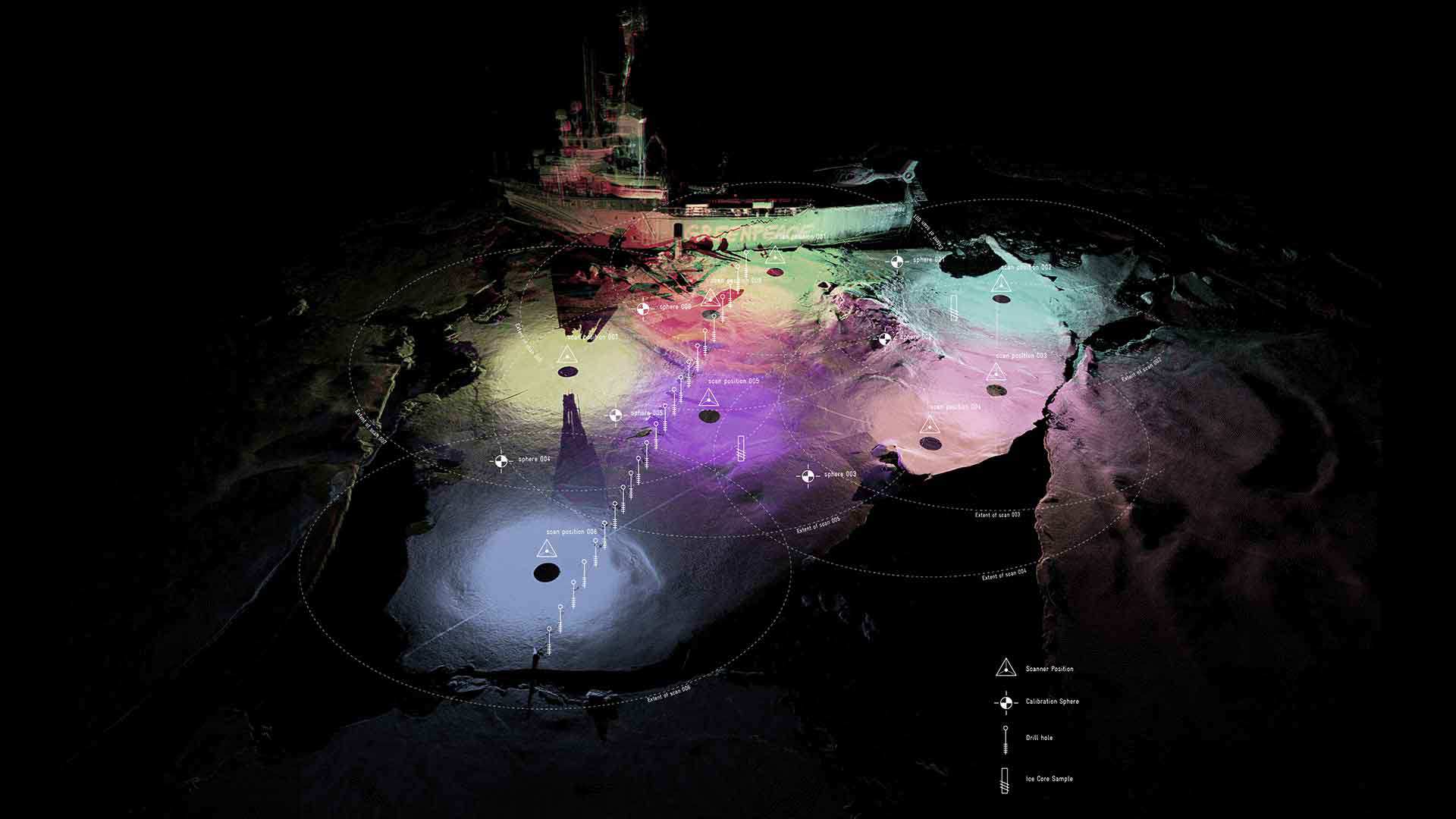

While working with sea ice scientists from Cambridge in the Arctic, for instance, our role was to oversee two tasks: we measured the Arctic Sea ice, gathering data to be used in complex mathematics for understanding how ice moves and behaves, and how it might break up. We also helped to calibrate between continental-scale information from satellites and empirical on-the-ground measurements.

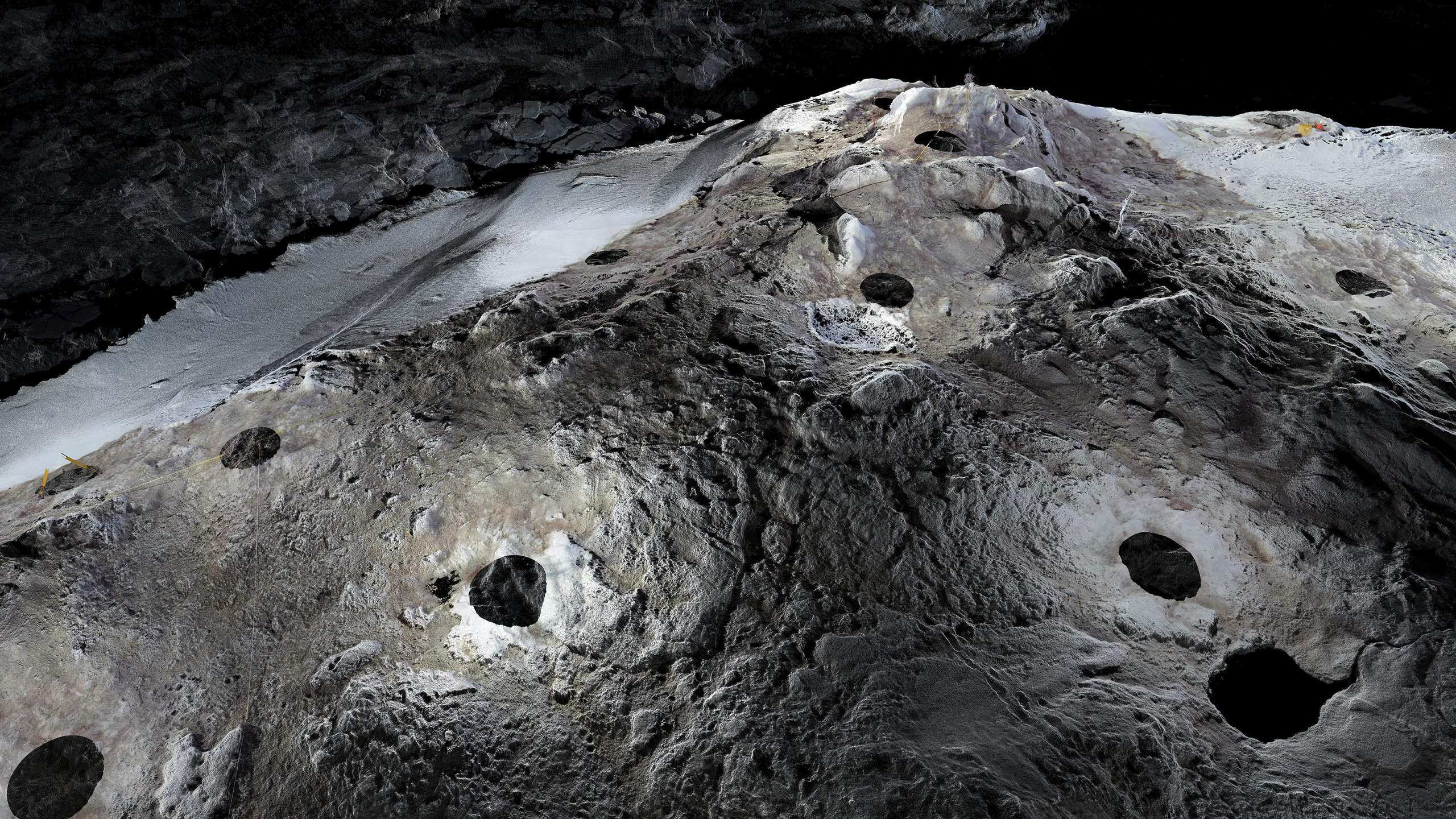

What struck us most about this project was the fact that the scientific data and research exists primarily in a mathematical domain, whereas our impulse was to use the detailed models of the ice to re-create this lost landscape and bring that remote location to visitors.

William Trossell, architect and ScanLAB co-founder, elaborates on the studio’s collaborations with scientific communities, the extents of the tool and potentials for future practice.

Your work involves collaborations with artists, museums, broadcasters, scientists and private companies, among others. In these collaborations, the spatial information you provide builds on other fields’ findings and expertise, often resulting in the production of new knowledge, evidence or stories. How do you manage the communication of your data across such diverse parties and disciplines? And how are different methods, techniques and scales (of measurement) merged in the process?

As humans, communicating through and navigating space are basic instincts, and our work tends to draw upon lots of conventions and magic within this language. We’re also informed by our background as designers, where we’ve honed our ability to take mathematics, data and stories, and turn them into visuals. As designers, our creative ambition — whether that’s through a sketch, a photo, or a render — is to tell theories through space.

We also don’t see laser scanning as just a measurement device. The scanner is also a camera, so a lot of our visual language and creative practice is based on photography, cinema and visual effects. We really enjoy that cross-pollination between different disciplines; each has an incredible story-telling workflow that has been designed and honed over the years, and we draw on those concepts to create our own work.

As you describe in a previous interview, your collaborations are often twofold in nature – engaging with the scanner as both ‘an “objective” measurement’ and a ‘subjective imaging device’. This is of course very telling given your particular stance between scientific and artistic production. In this regard, how would you recount your exchange with scientists as a creative practice? How do you think your involvement – as architects/designers/makers/coders – affects the process of scientific research?

While working with sea ice scientists from Cambridge in the Arctic, for instance, our role was to oversee two tasks: we measured the Arctic Sea ice, gathering data to be used in complex mathematics for understanding how ice moves and behaves, and how it might break up. We also helped to calibrate between continental-scale information from satellites and empirical on-the-ground measurements.

What struck us most about this project was the fact that the scientific data and research exists primarily in a mathematical domain, whereas our impulse was to use the detailed models of the ice to re-create this lost landscape and bring that remote location to visitors.

Arctic Climate Impact Tour. Diagram showing position of drill holes and scan locations © ScanLAB

Arctic Climate Impact Tour © ScanLAB

In both cases, though, we are offering a previously unseen perspective through the eyes of the laser scanner, allowing all audiences to see in ways they couldn’t before. I’d liken it to giving them a pair of binoculars, broadening their visual horizon.

Our involvement gives us huge satisfaction in that we are contributing to the scientific process, and that there is an opportunity in our creative response to having been there and collected that data to share an artwork beyond that scientific community.

The Arctic Climate Impact Tour is indeed a significant example of a research-turned-art, as the scientific expedition was followed by your exhibition ‘Frozen Relic: Arctic Works’. The rather extreme conditions of the fieldwork render the project all-the-more interesting. How would you reflect on this collaboration in terms of the tool’s extents and potentials?

Interestingly, when we went to the Arctic we didn’t actually know whether the scanner was capable of scanning ice, as the wavelength of the infrared that the laser used was not too dissimilar to some of the wavelengths that are actually absorbed by water.

On our second trip, we took multi-beam sonar from Wood’s Hole Oceanographic Institute in an attempt to scan underwater; this ended up proving challenging because of the elements and tides (not to mention the polar bears!).

LIDAR’s development was originally driven by NASA’s research, then by manufacturing, and then remained relatively static before being used again for autonomous vehicles and personal devices; this is driving down the size and cost of the instruments, and making them increasingly accessible. When we went to the Arctic, we took the scanner of its day, which cost around £150,000 and weighed around 25 kg. Today, many people have portable LIDAR scanners in their pockets — that just goes to show how quickly the technology has developed in a short time. We’re now seeing the use of 3D scanning diversifying enormously away from expensive grant-led research to our everyday lives, and unlocking uses we have not yet imagined. Pocket-sized 3D scanners give a whole new, diverse range of users the ability to explore new perspectives.

Frozen Relic: Arctic Works. A view of the melting ice in the gallery space © ScanLAB

Another interesting aspect of your work is its archival potential, for an always already present theme ‘running through your work’ (and built into the tool itself) is memory. This perhaps becomes most evident in a project as the Mail Rail Viewers. In relation to the field of Science, Technology & Society, what potentials do you see in 3D scanning as an archival practice?

In short, lots! 3D scanning can forensically record people, places and spaces, and the resolution of that capture is such that it can record the detritus of life and the narratives of a space. Once the data is recorded, it offers the opportunity to revisit those moments, or multiples of those moments. It can also be used for conservation and to monitor change over time.

The technology also offers an incredible opportunity to archive the personal — recording lived experience and memory and allowing us to revisit those memories. Particularly as 3D scanning has democratised, transitioning from something accessible only to a select few to a technology increasingly available on consumer smartphones, it has taken the ability to take a photo to memorialise a moment and added the capacity for that photo to contain depth.

The Postal Museum, The Mail Rail Depot, Network Explorer, installation view © ScanLAB

This raises interesting questions regarding how we archive data. Our digital media landscape, for want of a better phrase, has always evolved with the formats; music was stored on tapes, then CDs, then streamed from the cloud. In a similar way, how we store our memories has changed with the advent of new formats. We don’t yet know how that works for 3D scans; we are not yet at a stage where we can put all our scan data in a digital ‘box’ and easily pick memories out of that store. It will be interesting to discuss how we can archive places and moments in history and make them open and revisitable, rather than allowing those archives to become obsolete.

It’s also interesting to see how large neural nets are capable of storing imagery and recalling that world through prompts. Generative AI (text-to-image) models like Stable Diffusion aren’t just a huge database of photos; they are photos embedded into a model. This highly compressed database of billions of images as something which can be queried is really fascinating. What happens when we feed a 3D model of reality into that? How does having a compressed version of the world in a queryable model change the way we might recall – experience - interact with moments in space and time. What happens when these are personalised, not generalised?

The interior of Paquio Proculo and its extensive mosaic © ScanLAB

Given your creative engagement with the tool, I believe ScanLAB’s oeuvre is a sneak preview into those speculative and nonetheless imminent futures. Ending on these provocative questions, we’d like to remind our readers of ScanLAB’s upcoming exhibition as part of ‘Chaos & Memories’ at the PHI Centre, Montreal, which will be open to visitors from 22 March to 11 June 2023.

William Trossell is co-founder of ScanLAB Projects. He loves building new and extraordinary ways to expand our understanding of the material world. He graduated from the Bartlett School of Architecture but has been somewhat sidetracked as a creative technologist. With a keen interest in how the digital and its augmentation might impact our cultural heritage, Will has been working closely with Museums and World Heritage Sites around the world.

Published: 03/13/2023