Art and Nuclear Energy: Review of “Picturing the Invisible” Exhibition

Hannah Star Rogers06/12/2023 | Review

Exhibitions in the area of science and technology are social and political interventions. Art-science works offer spaces for reflection on our use of technology and the social and political results of this exchange. Exhibitions are thus fruitful venues for STS scholars to open channels for the public forum through art and technical materials. Curators must necessarily take a stance on the marking of their controlled public space as a site of intervention. As a scholar of STS, my curatorial practice is guided by this sensibility, which is increasingly informing projects that aim at public transparency.

My own efforts have been in the area of art, science, and technology, an area fraught with power differentials but also the potential to address complex problems. My interest in the question of what art and STS can do together resulted in a monograph, the Routledge Handbook of Art, Science, and Technology Studies (ASTS), and a number of exhibitions, including the traveling exhibition Shadows and Ashes: The Peril of Nuclear Weapons for Cornell University’s Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, which was based on a show Mary Hamill originated at Princeton University. The latter exhibition investigated the consequences of nuclear weapons on the technical and emotive senses by bringing together technical information about the proliferation and yields of nuclear weapons in recent decades, artworks, and opportunities for engaging visitors with the explicitly political goals of the exhibit. It is this experience of exhibiting art and STS about nuclear weapons that draws me to quite a different show, again engaging art and STS, but this time to explore the nuclear energy disaster in Japan in 2011: the multifaceted and innovative exhibition, Picturing the Invisible, curated by the STS scholar Makaoto Takahashi.

Into the growing space of art and STS exhibitions comes this well-composed photography exhibition on the aftermath of the tsunami and subsequent Japanese nuclear energy disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The exhibition originated as a way to call to attention the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima triple disaster, which was potentially overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. By organizing this art exhibition-memorial for the memory of "3.11," Takahashi offers a space for reflection on the timescale of such disasters.

The exhibition provides a striking photographic portrait of life in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster through the works of six photographers working in the affected territories. The effect of these works is further heightened and contextualized by companion essays written by policy makers, scholars, and activists. As Takahashi puts it, “Together these works make visible the otherwise overlooked legacies of 3.11: the ghostly touch of radiation, lingering traumas, and the resilience of the affected communities.” Thousands of workers continue working to remediate Fukushima Daiichi, to decommission the nuclear power plant and decontaminate the rings of radiation, particularly in the soil of the surrounding countryside.

In interdisciplinary exhibitions, the way artworks and technical materials are understood by visitors is always a central concern. STS scholarship has offered pathways to consider how knowledge products might be understood in symmetrical ways, but what is in the mind of a curator or scholar needs to be materially and textually translated for visitors. Picturing the Invisible’s subject matter presents new arguments for understanding nuclear energy's effects in multiple registers and invites their social meanings for public consideration. The line between facts and feelings in this exhibition points out the complexities of sorting art and science too clearly: as much as the expert information in this exhibition brings forward feelings for visitors, so, too, do the artworks display the consequences of nuclear energy.

Picturing the Invisible is a photography exhibition that casts a wide net over the genre offering video art, portraits, documentary photographs, early photography methods including daguerreotypes, and raw film exposed to radiation by burying it. At the same time, the curator has focused strictly on art made in response to Fukushima, as opposed to the upwelling of art on nuclear issues more generally. Among the most striking images is Lieko Shiga’s portrait of a farmer whose family had worked to clear the forests that once covered much of the prefecture around the Fukushima plant. This complex image asks viewers to reflect on the bodily and metaphorical connection between land and people, mediated through the trees harvested to allow for pastoral cultivation. In its mythical proportions, this image makes a striking addition to the exhibition, especially with the documentary images surrounding it, many of which show the mundane tasks of clearing away contamination on a scale so enormous that it becomes ubiquitous.

Lieko Shiga. Portrait of Cultivation, from the Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore) series, 2009.

For example, Rebecca Bathory’s series Return to Fukushima features the striking image of seemingly endless piles of black bags of topsoil: a symbol of contamination removal but also the lost livelihoods of local farmers. These piles of bags were stored in temporary locations across the country, but they are sites of an ongoing contestation and reminders of the growing science-communication failures of the disaster as the government continues to grapple with where they can be stored in the long term.

Rebecca Bathory. Return to Fukushima (series), 2016.

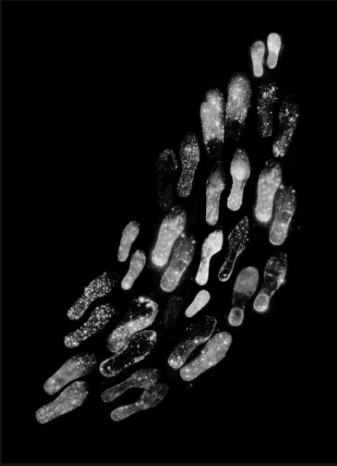

Masamichi Kagaya and Satoshi Mori form an art-science collaboration that has produced the Autoradiograph series, two pieces of which are displayed in this exhibition. Both images capture radiation on film and offer contrasting senses of its organization and effects. One image shows the contaminated shoes of radiation refugees and highlights the arbitrary nature of what we often speak of as predictable, as pairs of shoes sometimes show very different amounts of radiation. The other offers a biological order to the contamination as we see the growth of a cypress branch and the clusters of radiation forming a band across the needles.

Masamichi Kagaya and Satoshi Mori. Evacuation: Insoles, from the Autoradiograph series, 2018.

Masamichi Kagaya and Satoshi Mori. Cypress Leaves, from the Autoradiograph series, 2018.

Exhibitions like Picturing the Invisible make arguments for the future of technologies and offer space for conversations about such technologies. Producing a show explicitly meant to blur the boundaries between information hailing from art and science traditions, however, has particular considerations. Even when objects are produced or identified as part of the art or science knowledge community, the tension between the object and the context influences the interpretation of their meanings. In the case of the installation of Picturing the Invisible at Heong Gallery at Downing College, Cambridge, UK, the context is clearly artistic, and yet through the text panels accompanying artworks, the exhibition unfolds the expertise of scientists, policy makers, activists, and those who experienced the disaster — offering a complex and multivalent sense of the subject.

Further, the images in Picturing the Invisible and their accompanying essays raise questions about individual and collective action and inaction in the face of the production of aesthetic and technical evidence. STS scholars can play an important role in leveling the field between art and science around contentious issues, in this case, nuclear energy. By combining artworks and expert information, this exhibition opens conversations on the practical and philosophical implications of humans’ continued efforts to create and dismantle nuclear weapons. This assemblage explores the idea that understanding the consequences of the continued development of nuclear energy, both intended and unintended, requires social and political reflection. This multi-faceted exploration of the implications of nuclear energy enacts the impulse to approach such a complex subject from as many angles as possible. Through the scope and variety of its photographic and filmic media, the exhibition invites us to imagine its effects on individuals, the landscape, the nation, and the world. Bringing art and science together around a charged issue like nuclear energy offers an opportunity to consider different forms of knowledge and what they bring to public discourse about the past and future of technologies.

Special thanks to Makaoto Takahashi for providing the art and exhibition images used here.

References

Barnes, B., & Bloor, D. 1996. Scientific Knowledge: A Sociological Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Schoichet, G. 1986. Hibakusha: Documentary portraits and interviews. Interviewer Gary Schoichet, San Francisco, CA.

Hannah Star Rogers holds a PhD from Cornell University in Science and Technology Studies and an MFA from Columbia University. She is the lead editor of the Routledge Handbook of Art, Science, and Technology Studies and her monograph from MIT Press, Art, Science, and the Politics of Knowledge appeared in 2022. She is currently based at the University of Copenhagen where she is researching Metabolic Arts as part of a Novo Nordisk grant through the Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR).

Published: 06/12/2023