Energetics of Infrastructure in the Middle East

Katayoun Shafiee05/02/2024 | Reflections

Natural resource abundance and scarcity have long been associated with the history and politics of the modern Middle East, particularly in the twentieth century. The intensive construction of large-scale infrastructural projects around oil and water played a decisive role in shaping political possibilities for state building, political community, and forms of empire in the region. Deployed by Western firms and their host governments as projects of economic development, such projects were also radical experiments, organising humans and nature in novel and unexpected ways. They helped mobilise a set of unusual yet remarkable actor-technologies, including economic development contracts, formulas for calculating profits and productivity, forms of economic appraisal, and other tools to quantify and qualify human-nature relations.

While there is widespread awareness of the importance of water in the history of the modern Middle East, we know surprisingly little about how its social and technical properties have shaped that history, particularly the decision-making process of infrastructural appraisals.

This blog post shares one such case, the Dez Dam in Khuzestan province, southwest Iran, where the workings of cost-benefit analysis first played a pivotal role in the region. Calculating the economic costs and social benefits of dammed, hydroelectric energy from the Dez River versus oil-based thermal energy helped transfer the powers of water management from local and state actors to an American development firm (the Development and Resources Corporation, DRC) chaired by David E. Lilienthal. Lilienthal was the former head of the famed integrated river basin development scheme, the Tennessee Valley Authority. Such powers were also transferred to international regimes of economic and scientific governance, such as the World Bank.

Map showing the Dez Dam, the course of Dez River and Karun River in Khuzestan province, southwest Iran. [Image credit: “Karun river basin” by Shannon1 CC BY-SA 4.0]

Situated along the Persian Gulf, Khuzestan province was the home of the largest oil refinery in the world and the major oil-producing fields of the Middle East. Yet, US government development experts based in Iran argued that water, not oil, was “liquid gold,” and Khuzestan embodied major opportunities for irrigation, flood control and increased production of such foods as sugar[1]. In coordination with the DRC and the World Bank, this infrastructural agenda resulted in the building of the largest high-arch concrete dam of its kind in the region – the Dez Dam, renamed Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlevi Dam at its inauguration in 1963.

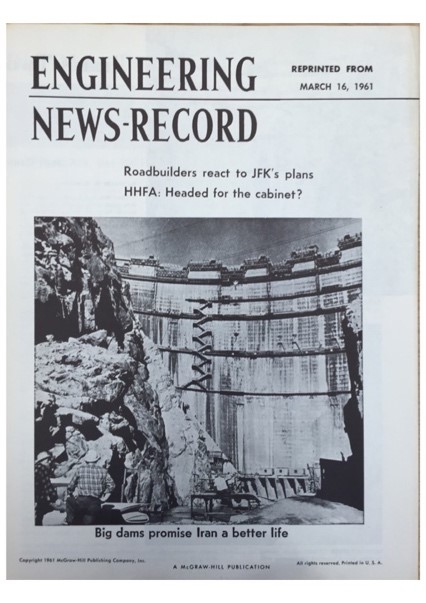

Iran’s Dez Dam in W Bowman, Iran’s Two Big Dams Promise a Better Life, Engineering News-Record, 16 March 1961, DRCP, SMLPU, Box 1, Folder 1. [Image credit: Katayoun Shafiee]

The role of cost-benefit analysis as a technology of governance

In the case of the Dez Multipurpose Project, the calculative work of cost-benefit analysis played a crucial role. It mobilised development experts, agricultural scientists, water technologists, engineers, and Iranian state officials in an enormous economic endeavour of harnessing nature to achieve food security for the nation.

Though plagued by inadequate data, there were three aims of the project: electrification of the towns from hydroelectric power, irrigation of potentially productive land along the Karun and Dez Rivers, and regulation of Dez river flow to diminish serious flood damage, especially between Ahwaz and the Persian Gulf.

In his 1966 appraisal of this project, John A. King, director of the World Bank’s Economic Development Institute, identified several problems to achieve the overall aim of improving “the quality of economic management in government in the less developed countries”. King highlighted the case of the Dez Dam project, which was granted an initial $42 million US dollars of funding out of a total estimated cost of $82 million. As if predestined to fail, King underlined the plethora of obstacles exhibited by this example and “inherent in any attempt to forecast in quantitative terms investment cost, operating cost, revenues and the return on projects in underdeveloped countries”.

Another Bank representative expressed scepticism: “Iran should learn how to crawl before it tries to walk” because the “return on investment shown for the project is not too favourable, and the risks are great”[2]. Problems of organisation, policy, and the uncertainties attached to the irrigation program rendered the Dez project so risky that other regions of Khuzestan were deemed more favourable.

However, DRC representatives countered that the economic feasibility of the Dez Dam was “guaranteed by its power and flood control benefits.” This would “offset” some of the risks of the irrigation program, it said. The “greatest advantage” of the multipurpose water control program was that power potential could be considered as a “paying partner … yield[ing] quite a substantial margin” to support other aims[3]. Lilienthal argued that it will bring the combined benefit of renewable sources of electrical energy and grassroots democracy for a profit to the global south.

Attempting to redefine itself as a development agency in the post-WWII order, the Bank did not want to lose its client – the Iranian government – nor did American public-private enterprise. While simultaneously excluding local farmers, decision-making within infrastructural appraisal exhibited a kind of economentality, making a difference not only for the survival of international governance and development but also for national questions of sovereignty and futurity, which were now understood in terms of economic growth. Over the course of three decades, the energetics of this infrastructure relied on a peculiar technology of computation that attached abundant flows of river water to a concrete dam, farmers, consulting engineers, irrigation works, and sugar. It enabled the dam project to survive despite the costs and risks attached from the start, including the saline soil.

The Dez project was completed in 1968 with disastrous results for the environment and local population, who continued to protest the scarcity of clean drinking water due to excessive irrigation schemes attached to large dams, causing many rivers to run dry. In the age of the Anthropocene, scholars in STS have for a while now considered what the political and technical are and how they work in riverine environments. Only by taking seriously the tools and arguments made available for handling the energetics of such large-scale infrastructure can we open the possibility for more democratic, smaller-scale solutions that transfer powers of decision-making and flows of water back to local stakeholders and riverine environments.

Katayoun Shafiee is an Associate Professor in the History Department at the University of Warwick, United Kingdom. This blog post is based on her second book manuscript about the risky measures of economic science, governance, and infrastructure transforming Iranian riverine environments in the 20th century.

Published: 02/06/2024