When ‘access’ is not enough: diversification of high school programs and the maintenance of social inequalities

Felipe Garcia Passos03/04/2024 | Reflections

Historically, there has been a general effort to extend access to basic education with new programs, particularly in countries like Brazil that struggle against deep social inequalities. However, these initiatives can also serve as a cautionary tale on why new programs might not suffice in terms of diminishing historical injustices. In fact, they can solidify dominant educational policies and perpetuate economic, racial, and geographic inequalities. This is particularly important as STS scholars have advocated for new modes of teaching to foster the production of ethical knowledge (Catanzariti, 2024). The following piece offers a brief cautionary tale on how the inclusion of full-time programs and increased access to the public high education system in Brazil do not necessarily create new opportunities for social mobility but can rather reinforce old structures that perpetuate inequalities.

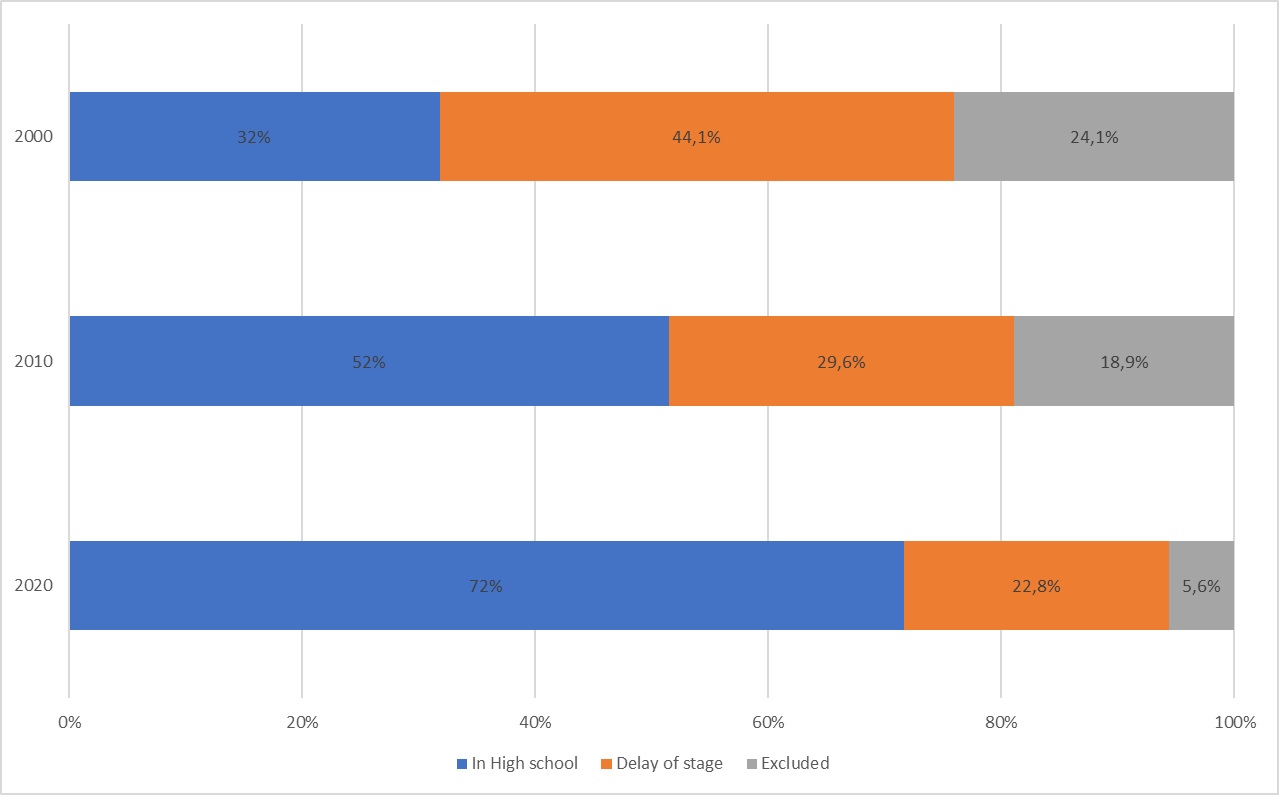

In Brazil, compulsory high school attendance for under 18 years old only started in 2013, thanks to a government mandate extending the requirement even to those who were lagging behind. Enrollment in this stage had been steadily increasing, predating the implementation of this new law. The growth was attributed to the historically low access rate to high school, a rising number of elementary school graduates, and societal pressure for a more inclusive high school stage (Corti, 2019). Figure 1 illustrates the rates of exclusion, delay, and on-time students enrolled in schools in Brazil from 2000 to 2020.

Evolution of school access and delay of 15-17 age population (Brazil, 2000 - 2020) [Image credit: Demographic Census (2000, 2010); PNAD (2019, 2021)]

Researchers confirm that this growth begins to reduce inequality in high school access among individuals with higher and lower incomes, black and white populations, and rural and urban areas. However, class, race, and geographical criteria continue to significantly influence exclusion and academic delays in basic education (elementary + high school) today (Brito, 2017; Simões, 2019).

While acknowledging the importance of continuously increasing access, it is also crucial to analyze how the expansion of enrollments has unfolded, particularly considering that the growth of high school in Brazil is occurring through a series of reforms aimed at making the provision of formal school education more flexible.

Recently, Tartuce et al (2018) investigated the implementation of various high school programs in ten Brazilian states. Their paper distinguishes between two main types of offerings. The first is full-time teaching, either integrated or not with subsequent technical courses, typically provided in urban areas for those who already have access to regular high school. The second type aims to reach rural communities where there are no existing high schools. In this case, there are two alternative programs. One offers classes through television with a local teacher providing support to the students, and the other is a modular teaching educational system. In terms of quality, one can find a disparity among high school programs that are inaccessible to all students. Due to a lack of equitable support and availability limited to specific regions, access to each program depends on the student's social circumstances.

This array of public high school offerings with varying conditions creates a run among families and students for the best possible enrollment. From the urban full-time program to the rural TV-classes program, a social stratification is reinforced by public secondary education in Brazil. In São Paulo, the full-time program excludes the most vulnerable students (Girotto & Cássio, 2018), while in the Brazilian Amazon, the TV-classes program (see Figure 2) serves as a cheap way to provide high school education in the rural areas where riparian, quilombolas, peasants and indigenous communities live, groups historically marginalised by the State (Matos, Reis & Couto, 2021).

Figure 2 - TV-classes program in the Amazon region, state of Pará [Image credit: Author]

In the State of São Paulo, 44% of regular high schools (part-time) transitioned to the Full-time Teaching Program (PEI, in Portuguese) in 2023 without offering any form of economic assistance to support vulnerable youth in their studies now that they attend full-time schools. The program ignores that work activities serve as the primary reason for high school-age individuals dropping out in Brazil. Many of them need to contribute to their families' income or assist in family-run informal businesses at some point during the day. As a result, there was an increase in the number of mothers with university education in PEI schools and a decrease rate in regular schools adjacent to PEI institutions (Girotto & Cássio, 2018).

The stratification of opportunities presents itself differently in the state of Pará, as well as in other states in the North and Northeast regions. The Teaching Interactive System (SEI, in Portuguese) is one case. The program was launched to serve numerous communities across 86 out of 144 municipalities without high schools in rural areas. This program is based on classes broadcasted over the internet within a designated room in elementary (municipality) schools, with a single in-person tutor assisting each class. The classes, syllabus, and calendar remain uniform across all communities, regardless of whether they are located on islands, in mangroves, forests, or along rivers.

In São Paulo, the PEI program selects the least vulnerable students, while in Pará, the government includes marginalized individuals in the high school stage without providing proper school facilities, teachers, syllabus tailored to students' culture, or appropriate academic calendars. Consequently, families feel a responsibility to enroll their children in the best schools available, if they have a choice.

Current research in Brazil highlights an expansion of secondary education that perpetuates social inequalities through public educational policies implemented in diverse ways and based on the characteristics of each region. Contrary to common belief, such expansion does not offer an opportunity to alter the social conditions of social classes; rather, it manages and sustains a historically constructed stratification in the country, reinforcing economic, racial, and geographic inequalities.

One approach to mitigating inequalities through educational policies is by providing financial and educational support to the most vulnerable families so that their students can access any program. There is also a need to dismantle the pathways that create unequal schools depending on their location, whether between different areas within cities or between urban and rural areas. To achieve this, a legal mechanism for fair economic investment is required to guarantee infrastructure quality and teacher training regardless of where basic education is offered. A strategic spatial distribution of schools is crucial in this regard. Creating opportunities to train local teachers and developing curricula tailored to meet the needs of traditional populations is also necessary. These equitable policies are essential actions, but they stand in contrast to the current neoliberal reforms in Brazil.

____________________

Felipe Garcia Passos is Professor at the Federal Institute of Pará (IFPa) and a PhD candidate at the Department of Geography, University of São Paulo (USP). His research focuses on how current public policies produce spatial educational inequalities in Brazil.

Published: 03/04/2024