“Laughable Science”: The Irish Government’s Response to the Crumbling Homes of Donegal

Kaitlyn Rabach04/22/2024 | Reflections

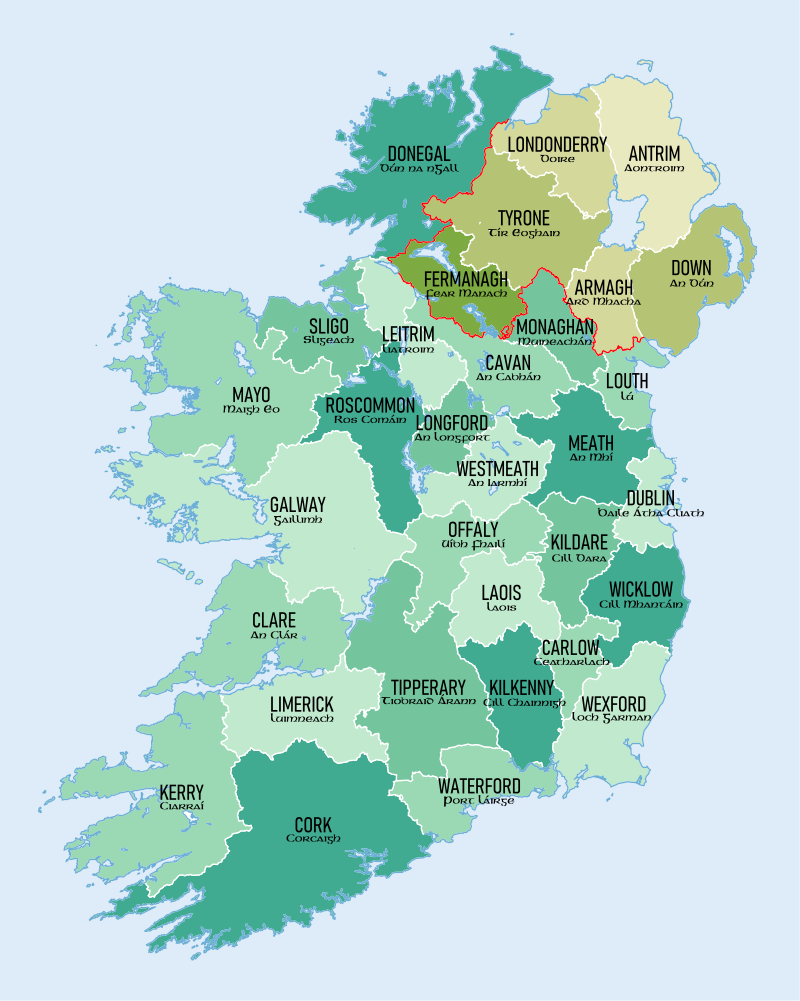

Positioned in the far northwest of Ireland, Donegal—the nation’s “forgotten county”—is home to the largest land border between Ireland and Northern Ireland (Figure 1); as a result of regional isolation, Donegal has faced devastating government policies resulting in years of economic neglect and “exhausted” infrastructures (Fortun 2014).[1] One such infrastructure, the subject of this post, is the deteriorating concrete architecture that dominates the built environment in Donegal, including its homes, schools, medical facilities, roads, sewage systems and more.[2] Today, an estimated 30,000+ homes in Donegal are crumbling due to the failure and neglect of a self-regulated construction industry without a comprehensive independent audit or inspection system.[3] Though defective concrete has been discovered in other Irish counties,[4] Donegal remains the epicenter of the disaster.

Figure 1: Map of the island of Ireland showing the partition between Ireland and Northern Ireland. [Image credit: Wikipedia Commons]

Over a decade of delayed governmental response has left some homeowners living in uninhabitable conditions with severe dampness and mold, electrical risks, structural instability, severe cracking, and crumbling homes (Figure 2). Even low estimates of the cost to address just the housing aspect of the crisis exceed 3.2 billion euros. Further complicating matters, MICA—the mineral long thought to be the main cause of the “Weetabix” blocks and the crux of the original redress legislation, the “Enhanced Defective Concrete Blocks Grant Scheme”—has recently been revealed to be falsely diagnosed by government experts as the reason why concrete buildings are crumbling. This misdiagnosis has resulted in severe implications for the remediation and rebuilding processes and has also exacerbated activists’ distrust in the government’s handling of the disaster, particularly regarding the geology behind the government’s attempts at redress.

Figure 2: In Donegal, many live in uninhabitable domestic conditions with structural fragility. [Image credit: Angela Tourish]

Based on 12 months of fieldwork among Donegal’s defective concrete homeowners, activists, local builders, and politicians, my ethnographic research shows how the durability of what is now being called the “MICA Myth” in Donegal benefited various stakeholders, including the quarries at the heart of the scandal, the Irish National Standards Authority, and various governmental entities who assisted in the drafting and execution of the defective concrete grant scheme, such as the National Housing Agency and the Donegal County Council. In many ways, the continued slow resistance from elected politicians to accept newly emerging independent scientific studies debunking the “Mica Myth” echo other controversies of lighthearted attitudes and responses to scientific expertise in Ireland.[5] Donegal’s current housing disaster is thus a window into the ways in which contested claims to scientific truth and authority are rendered concrete as slow, infrastructural crises are continually shaped by citizens, local politicians, regulatory regimes, material actors, and broader political dynamics.

“Laughable Science” and a Grave Misdiagnosis: MICA vs. Iron Sulfides

For over a decade, Donegal homeowners have appealed to various levels of the Irish government—the Donegal County Council, the Housing Agency, and national politicians—to not only acknowledge the crisis of their crumbling homes, but to use robust scientific methods and solutions to address the crisis.[6] These calls have been answered with what many homeowners refer to as “laughable science.”[7] In 2015, the Irish National Government set up an expert panel review to investigate not the cause, but “to carry out a desktop study[8] … to establish the nature of the problem in the affected dwellings [emphasis added].” The panel also included a disclaimer stating:

“DISCLAIMER: The Expert Panel did not commission or carry out any tests on buildings or building materials itself and was dependent on technical information supplied directly to it by homeowners and concerned parties. The Panel have no responsibility for the accuracy of the technical reports and information received by it and the Report should be read in that light. It was not part of the Panel’s remit to apportion responsibility for any building defects drawn to its attention and it has not do so [emphasis added].”

The subsequent policy for homeowner redress, named IS465, concludes that MICA is the main culprit for the crumbling blocks. By attending to the “nature” of the problem in Donegal, and not necessarily the “cause,” the report displaced the crisis from its historical and political moorings, isolating the concrete block from the many entanglements and sociopolitical relations required for its extraction, formation, and finally marketization (Appel 2012).

Unsatisfied with the expert panel’s handling of the science, especially the fact that no physical materials from homes were being tested, Donegal homeowners began to reach out to other international activists and experts to better understand the differences in structural damage between MICA, pyrite and pyrrhotite. Aware of a previous pyrite scandal in Dublin just years prior (Doherty 2022; Hawkins 2014), homeowners became concerned that MICA was not the only aggregate to blame. Though many of these blocks do have high contents of MICA, subsequent independent research by international geologists, based on physical testing of concrete blocks, concluded that iron sulfides, specifically pyrrhotite, caused the severity of the deterioration of the homes, debunking the results of the previous government-led expert panel (Leemann et al. 2023).

During the early to mid 2000s when many of these homes were built, MICA did not have clear European standards, but iron sulfides did, and the blocks were well over the standards. This means the quarries producing the blocks were in breach of European standards and the Irish National Standard Authority failed to monitor harmful aggregates being sold on the Irish market. As early as 2013 to 2014, homeowners raised concerns about quarries to the standards authority and Donegal County Council; however, the council continued to award public tenders to the suspected quarry for years, angering many affected homeowners.[9]

Identifying the main cause of crumbling as iron sulfides not only has legal ramifications[10] but is also vital to understanding the remediation and rebuilding process of these homes. If only MICA were found in the blocks, remediation options could be used to repair the home, including the removing, and replacing of just the outer leaf blocks of the home. Iron sulfides, however, have no remediation options. Once iron sulfides are present in the blocks, scientists recommend full demolition, including stripping the home’s foundations to ensure no future deterioration and damage. The cost of remediation options versus full demolition is suspected by homeowners as another incentive as to why MICA would have been a preferred aggregate to be found in the blocks.

Contesting “Laughable Science”: Toward a Science of Redress

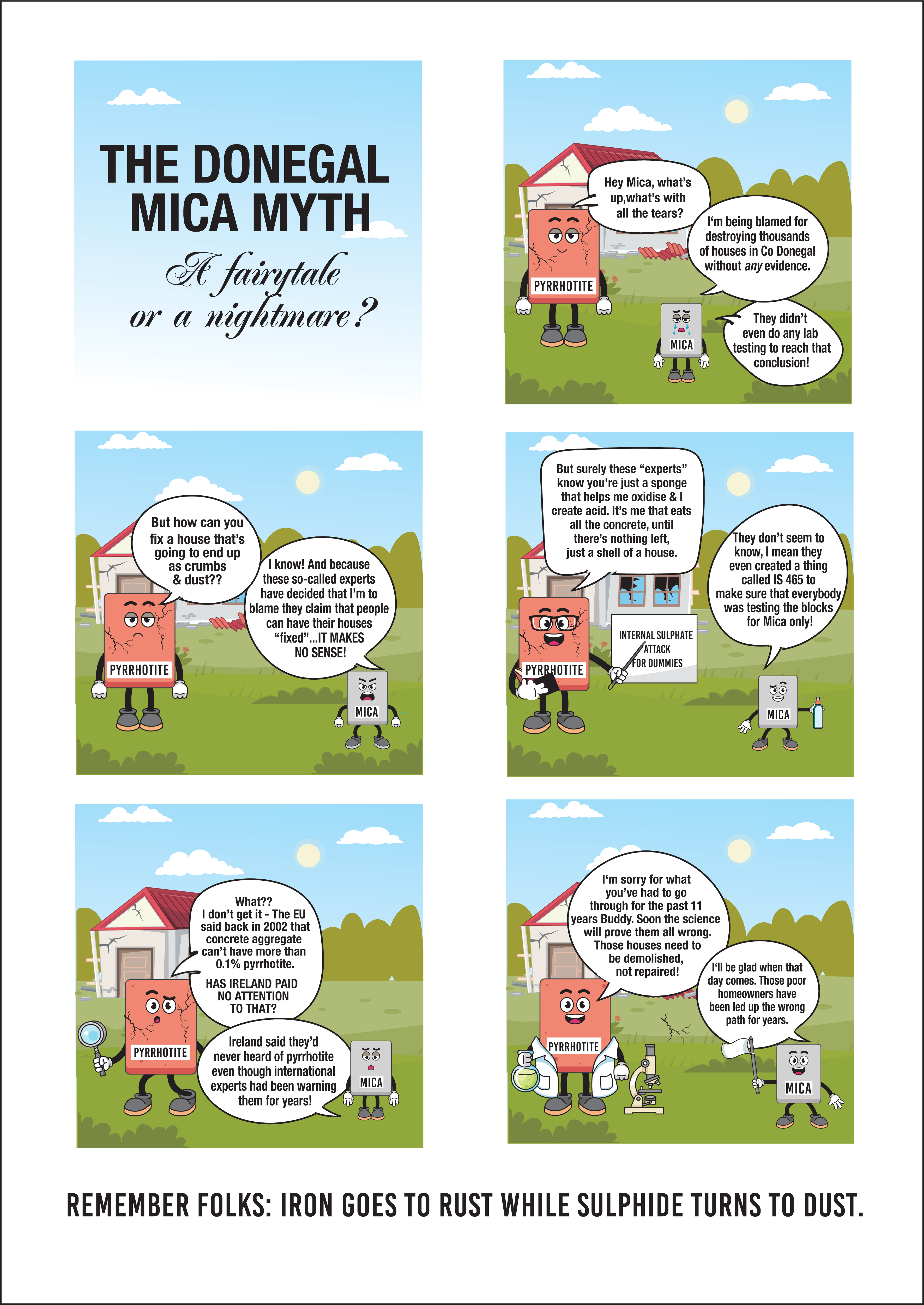

Despite the independent scientific evidence debunking the “MICA Myth” in Donegal, the myth continues to prevail both in government and among the public. Many Irish citizens and taxpayers continue to believe MICA is the main culprit; they do not understand why homeowners are calling for complete demolition of their homes rather than cheaper remediation options. Homeowner activists are appealing for 100% compensation to rebuild their homes and working to combat the lingering consequences of the government’s “laughable” expert panel. In doing so, they have turned to centering the science in their independent efforts for redress. Their centering strategies include participating in a conference titled “The Science and Societal Impacts of Defective Concrete” in the fall of 2022, hosting information meetings for other homeowners and citizens to learn about the differences between MICA and iron sulfides, and creating public information campaigns such as the comic below (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Homeowner-activists in Donegal today create and share comic strips to demystify the 'MICA Myth.' [Image credit: Debra MacCoy and Brenda Tierney Joyce]

In some cases, homeowners have pressured politicians to publicly accept scientific evidence. In one particularly heated moment, homeowner activists expressed deep dismay and outrage as Senator Niall Blaney admitted to not engaging with the peer-reviewed scientific article concluding iron sulfides were to blame for the damage.[11] For homeowners, having the knowledge of these international studies carries weight and power as they move forward in their activism. Yet selective ignorance and disengagement from the science among certain elected officials has served as a protective asset and organization tool (McGoey 2012). The stakes of this slow disaster include the billions of taxpayer euros that are being used to slowly remedy the crisis, but perhaps more importantly, the disaster is changing the relationship between affected homeowners and their trust in government officials and agencies. Many homeowners I interacted with demanded to “know the truth!” about the cause of the crisis and expressed concerns about “what else we just don’t know when it comes to them [referring to elected officials].” One thing we can conclude for sure is that this case is changing the ways affected homeowners in Donegal consume and interrogate the science that is presented to them. They are demanding their policies, especially redress polices, be driven by “evidence-backed science” and expertise. They are calling for peer-reviewed sources of knowledge. And they are not accepting “laughable” studies conducted from a desktop.

Author Bio

Kaitlyn Rabach is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine. Her research and teaching focus on environmental injustice and governance, failing infrastructure, toxic politics, and conceptions of home and homeland in Ireland.

Editor's Comment

Richard Fadok edited this post with assistance from Aaron Gregory and Ashton Wesner.

Footnotes

[1] The partition of Ireland in the early 1920s had a profound impact on County Donegal. With over 90 percent of its land bordering Northern Ireland, County Donegal not only faced regional isolation but also devastating post-partition policies. To this day, there are no train lines that connect Donegal with the rest of the Republic of Ireland; the county suffered several bombings and assassinations during the Northern Irish Troubles; and, most recently, the county is one of the last in Ireland to be connected to high-speed broadband and is still waiting to be connected to the national gas network. For an in-depth history of County Donegal, see An Historical, Environmental and Cultural Atlas of County Donegal (MacLaughlin 2013). For news articles on Donegal’s “forgotten county” narratives and the most recent impact of Brexit on the county, see “Donegal fisherman say Brexit change is endangering their lives” and “Donegal risks becoming ‘collateral damage’ from Brexit.”

[2] On how the world became “addicted” to concrete, see Jappe (2021). For a comprehensive history of concrete, including the ways concrete became ubiquitous with modern infrastructure, see Forty (2012).

[3] For in-depth building regulation policies, visit the following site: https://revisedacts.lawreform.ie/eli/1997/si/496/front/revised/en/html; For a detailed history of building “defects” during the Celtic Tiger years in Ireland, see Defects: Living with the Legacy of the Celtic Tiger (Ó Broin 2021).

[4] To read more about defective concrete in other Irish counties, see https://www.rte.ie/news/2022/0424/1294028-defective-blocks/

[5] For instance, Senator Niall Blaney, who has been slow to accept new evidence of iron sulfides, especially in homes’ foundations, was also a part of the “Golfgate” scandal in August 2020 where several prominent Irish politicians and public figures attended an 80+ person gathering disregarding new restrictions and health guidelines to slow the spread of COVID-19. Like newly emerging studies on COVID-19 (Caudill 2023; Grundmann 2023), the Donegal concrete disaster can be studied to better understand changing perceptions of authoritative science and expertise.

[6] For an extensive timeline on Donegal’s crisis of defective concrete, see “Ireland’s Timeline: On the Precipice,” published in 2023 by the activist Debra MacCoy. Working with homeowners, activists, and international scientists, MacCoy has recently published the first extensive timeline investigation of the MICA Myth and its origins.

[7] For many homeowners, the term “laughable” was used not only to describe the expert panel review, but also the government’s response to handling other aspects of this crisis, including significant delays with reimbursement funds, lack of establishing temporary living conditions for families having to rebuild, and not implementing an end-to-end scheme for particularly vulnerable homeowners, such as the elderly.

[8] In this case, the “desktop study” means the commission only reviewed technical information provided to them by homeowners and other concerned parties. The commission did not carry out any physical testing or investigations themselves.

[9] Only in 2022 was a government audit of the market surveillance of construction products in Donegal Quarries published: https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/6489d-publication-of-report-of-the-market-surveillance-of-construction-products-produced-from-county-donegal-quarries/. The audit took place in 2021, almost a decade after homeowners first reported deformities in products being produced by a local quarry.

[10] To read more about homeowners’ multi-party ongoing legal action in the Irish High Court, see https://colemanlegalpartners.ie/mica-defective-block-scandal-coleman-legal/.

[11] For a recap of this particular exchange at a political townhall in May 2023, listen to activists Charlie Ward and Mary Connors speak on the Upset in Concrete podcast: https://upsetinconcrete.backstory.ie/e/9-charlie-ward-mary-connors-speak-about-charlie-mcconalogue-s-latest-public-meeting/

References

Appel, Hannah. 2012. “Offshore Work: Oil, Modularity, and the How of Capitalism in Equatorial Guinea.” American Ethnologist 39 (4): 692–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01389.x.

Caudill, David Stanley, and Harry Collins. 2023. Expertise in Crisis: The Ideological Contours of Public Scientific Controversies. Bristol Shorts Research. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Coleman Legal Partners. “Defective Block Scandal.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://colemanlegalpartners.ie/mica-defective-block-scandal-coleman-legal/.

Cox, Aengus. “Expert warns defective blocks likely more widespread and scheme could cost 5bn euro.” RTE, April 24, 2022. https://www.rte.ie/news/2022/0424/1294028-defective-blocks/.

Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage. Remediation of Dwellings Damaged by the use of Defective Concrete Blocks Regulations 2023. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/1291c-remediation-of-dwellings-damaged-by-the-use-of-defective-concrete-blocks-regulations-2023/.

Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage. Report on the Expert Panel on Concrete Blocks. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/0218f-report-of-the-expert-panel-on-concrete-blocks/ referrer=https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/report_of_the_expert_panel_on_concrete_blocks.pdf.

Doherty, Eileen, Marian Carcary, Elaine Ramsey, Daniel Kelly, and Paul Dunlop. 2022. “An Examination of Governance Failure by the Irish State: The Critical Case of the ‘Mica’/Defective Blocks Issue.” European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance 18 (1): 154–63. https://doi.org/10.34190/ecmlg.18.1.934.

Fortun, Kim. 2012. “ETHNOGRAPHY IN LATE INDUSTRIALISM.” Cultural Anthropology 27 (3): 446–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2012.01153.x.

Forty, Adrian. 2012. Concrete and Culture: A Material History. London: Reaktion Books.

Grundmann, Reiner. 2023. Making Sense of Expertise: Cases from Law, Medicine, Journalism, COVID-19, and Climate Change. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis group.

Hawkins, A. B. 2014. Implications of Pyrite Oxidation for Engineering Works. Cham: Springer.

Hodges, Ron, Eugenio Caperchione, Jan Van Helden, Christoph Reichard, and Daniela Sorrentino. 2022. “The Role of Scientific Expertise in COVID-19 Policy-Making: Evidence from Four European Countries.” Public Organization Review22 (2): 249–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00614-z.

Law Reform Commission. Building Control Regulations 1997: Revised Updated to 1 July 2021. https://revisedacts.lawreform.ie/eli/1997/si/496/revised/en/html

Leemann, Andreas, Barbara Lothenbach, Beat Münch, Thomas Campbell, and Paul Dunlop. 2023. “The ‘Mica Crisis’ in Donegal, Ireland – A Case of Internal Sulfate Attack?” Cement and Concrete Research 168 (June): 107149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107149.

Jappe, Anslem. “Can we cure our addiction to concrete?” Signe, May 29, 2021. https://www.pavillon-arsenal.com/en/signe/11989-can-we-cure-our-addiction-to-concrete.html.

Mac Laughlin, Jim, and Seán Beattie, eds. 2013. An Historical, Environmental and Cultural Atlas of County Donegal. Cork, Ireland: Cork Univ. Press.

Magnier, Eileen. “Donegal Fisherman say Brexit change is endangering their lives.” RTE, January 14, 2021. https://www.rte.ie/news/2021/0114/1189701-fishing-brexit/.

McClements, Fred. “Donegal risks becoming ‘collateral damage’ from Brexit. The Irish Times, June 22, 2018. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/donegal-risks-becoming-collateral-damage-from-brexit-1.3540451.

McGoey, Linsey. 2012. “The Logic of Strategic Ignorance.” The British Journal of Sociology 63 (3): 533–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2012.01424.x.

Ó Broin, Eoin. 2021. Defects: Living with the Legacy of the Celtic Tiger. Co. Kildare, Ireland: Merrion Press.

O’Reilly, Rita. “Mould and debt add to homeowners’ mica and pyrite nightmares.” RTE, Sept 7, 2023. https://www.rte.ie/news/primetime/2023/0905/1403578-mould-and-debt-add-to-homeowners-mica-and-pyrite-nightmares/.

“Q&A: What is GolfGate and why is it causing Ireland problems?” BBC, Aug 26, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53881363 .

Redress Focus Groups. “20 Year Timeline of the Defective Concrete Crisis.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://redressfocusgroups.ie/20-year-timeline-of-the-defective-concrete-crisis/.

UlsterUniGES. “The Science and Societal Impacts of Defective Concrete.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXyP-xbe-20.

Upset in Concrete. “Charlie Ward & Mary Connors: McConalogues Meeting.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://upsetinconcrete.backstory.ie/e/9-charlie-ward-mary-connors-speak-about-charlie-mcconalogue-s-latest-public-meeting/.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Counties of Ireland,” Wikipedia, the Free Enclyclopedia. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Counties_of_Ireland&oldid=1209885894.

Published: 04/22/2024