Follow the Photographs: Networks in and beyond the medical archive

Michaela Clark04/29/2024 | Reflections

Introduction

The invention of photography in the nineteenth century was a turning point for both art and science. Medicine was quick to take up the medium with its promise of visual accuracy that was unachievable via other modes of imaging. Clinical photographs thus served as medical evidence, teaching aids, and institutional records. Yet they are more than just visual. They are also things that travel to form a part of larger global networks of medical knowledge and depictive technologies.

The University of Cape Town (UCT) Department of Surgery (DoS) Collection is one example in which such a network can be traced. Produced at South Africa’s first medical school, its photographic contents testify to connections between historical actors and institutions as well as imaging processes and print media across national and even international boundaries over six decades (from the 1900s to 1960s). Following the collection outside the settler-colonial medical archive offers insight into how clinical photography crossed scientific and lay terrains, and continues to bridge local and global space and time.

Assessing the UCT DoS Collection [Image credit: Author]

Photographs as Historical Objects

Photographs offer a unique source of information on the medical past. They may capture unintended details or what Deborah Poole calls ‘excess description’. In studying the history of medicine, it is this photographic excess that, in the words of Jeffrey Mifflin “can contribute much to our understanding of people, situations, and relationships not addressed by materials such as letters, diaries, administrative records, and journal articles”.

But there is more to a photograph than its visual content. Rather than two-dimensional images, they are physical things with three-dimensional attributes. They are ‘social’ objects that, to quote Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, “mov[e] through space and time” and connect not only human but non-human actants. Involved in the photographic process are the photographer and the sitter as well as the technologies of the camera and the chains of reproduction, distribution, publication, and storage. All of these leave traces that can be followed.

The UCT DoS Collection

While no records exist about the making and use of the UCT DoS Collection, the oldest material provides ample insight into its early ‘life’. Cabinet cards made by self-proclaimed ‘Art Photographer’ RE Ruddock in Newcastle-on-Tyne’s Goldsmiths Hall show how clinical photography crossed both disciplinary and geographical boundaries by entering the professional portrait studio and travelling from Britain, where it originated, to South Africa.

Clinical Cabinet Card made by RE Ruddock Photographic Studio in Newcastle-on-Tyne [Image credit: UCT Pathology Learning Centre]

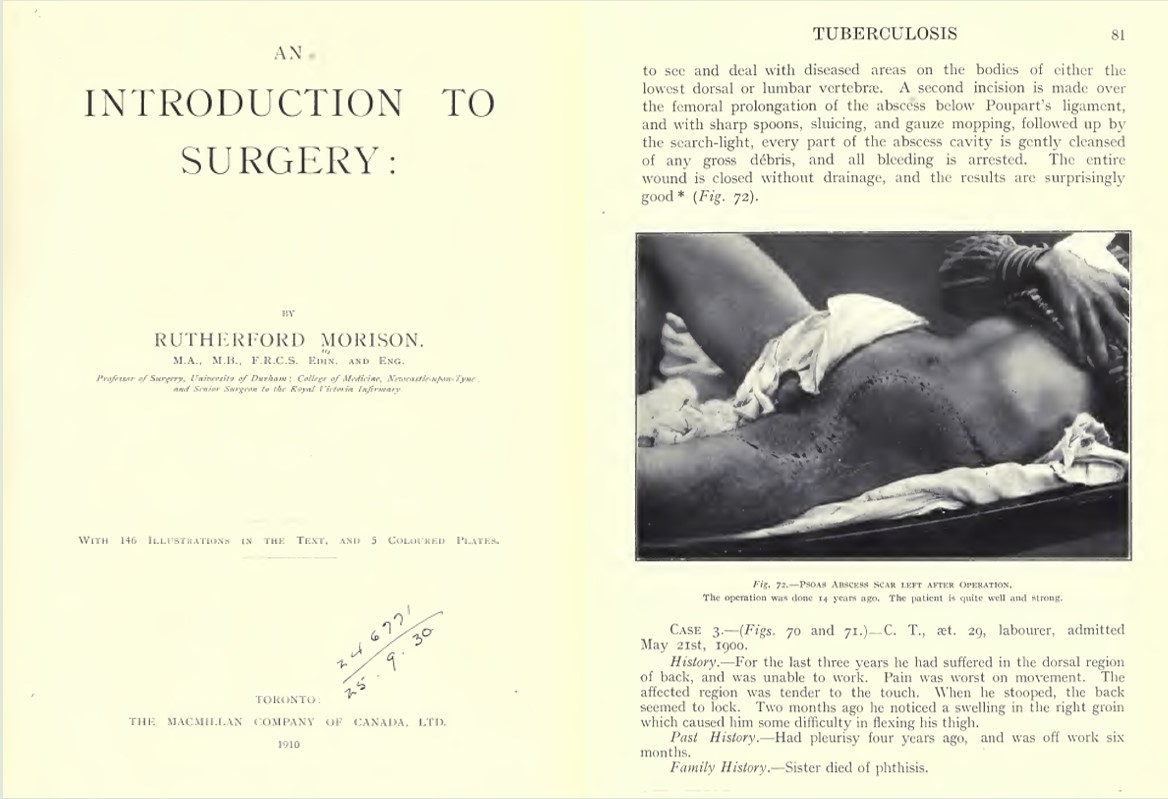

Many of these items were brought to Cape Town by the first head of Surgery at this city’s medical school, Charles Frederick Morris Saint. Saint had arrived in South Africa in 1920 bringing with him photographs associated with his mentor James Rutherford Morison – a turn-of-the-century surgeon at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle-on-Tyne. Along with these records, Saint also imported his mentor’s visual approach to surgical training that celebrated history taking and physical examination both in person and through the photograph. For it was Saint, with the help of his division’s technical assistants, who was to be the progenitor of clinical photography in Cape Town’s Department of Surgery.

Pages from JR Morison’s An Introduction to Surgery (1910) [Image Credit: John Wright & Sons Ltd.]

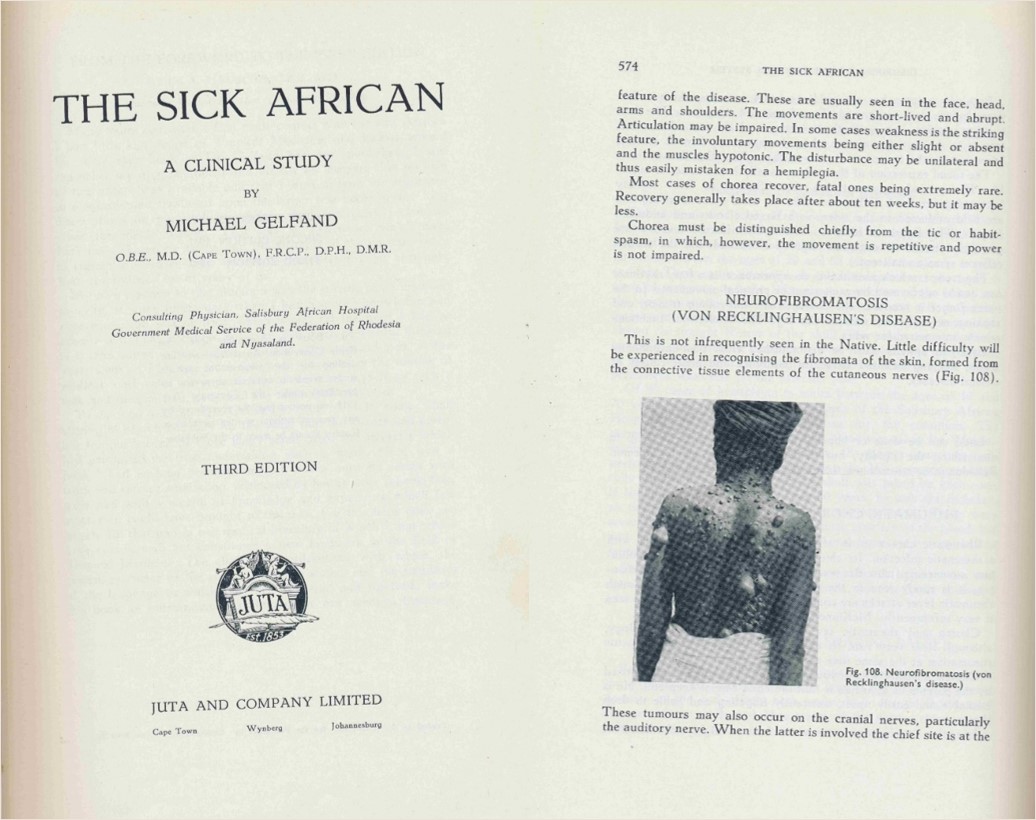

For the UCT DoS Collection to serve as a teaching aid to student surgeons, it needed to be expansive and complete. Although produced in a settler-colonial setting, Cape Town is a ‘temperate’ region of South Africa where ‘tropical’ diseases typically associated with the colonies are rare. To rectify matters, photographs of such conditions were obtained from beyond the country’s borders, most notably through a clinical colleague, Michael Gelfand, working in neighbouring Rhodesia (today’s Zimbabwe). Known for his book The Sick African in which some of these photographs feature, Capetown-trained Gelfand shared his clinical photographs with his alma mater.

Pages from M Gelfand’s The Sick African (1957) [Image Credit: Juta & Co. Ltd.]

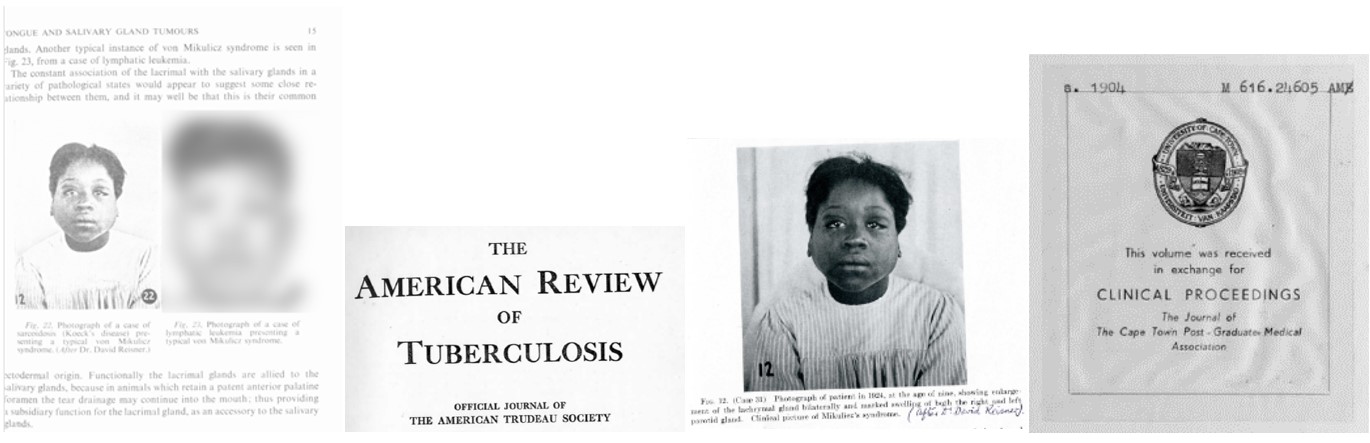

Exchanges of this kind extended further abroad, with Saint repurposing photographs produced as far afield as the US. The physical source of one example – a volume of the American Review for Tuberculosis – itself bears traces of transatlantic interchange: the entire journal (currently located at UCT’s health sciences library) was traded for a volume of the medical school’s journal, Clinical Proceedings.

Published iterations of the same clinical photograph of a patient and their sources [Image Credit: Cape Town Post-Graduate Medical Association; American Thoracic Society; Author]

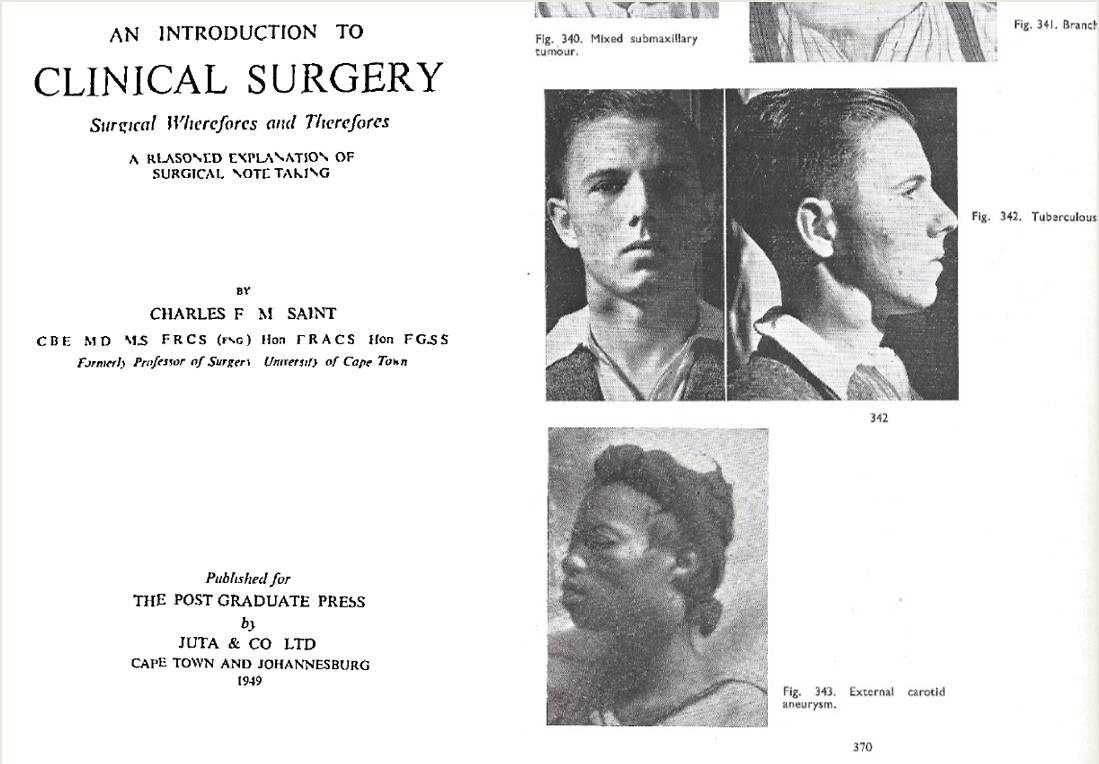

Such international exchange was possible because the contents of the UCT DoS Collection were made to function as universal exemplars – entities that exist outside of time and space. Photographs taken in the 1920s were repurposed and reproduced almost 30 years later, uprooting the records (and the patients depicted) from the context of their making. They operated as free-floating and ageless, perpetuating the universal ethic of biomedical knowledge that, no matter the source, clinical evidence is clinical evidence.

This too applies to race. While Cape Town hospitals were divided along racial lines, and everything from administrative documents to cutlery and blankets was colour-coded according to racial difference, the photographs rarely make a note of race. Instead, when published in international journals and textbooks, both white patients and patients of colour are neutrally harnessed as ‘clinical teaching material’ (to use a phrase of the time).

Pages from CFM Saint’s An Introduction to Clinical Surgery (1949) [Image Credit: Juta & Co. Ltd.]

Following the Flow

Today, publications featuring photographs from the UCT DoS Collection continue to circulate, albeit in a different form. Digitised and hosted online via repositories like The Internet Archive and Sabinet African Journals, distorted yet legible versions are accessible to the public. Rather than stable in meaning or ‘immutable’, they shift according to context and circumstance. While originally made towards clinical ends, now they serve as historical evidence. They thus operate as what John Law and Vicky Singleton call ‘fluid’ objects – material entities whose physical structure and network of relations gradually change, bit by bit, in a gentle flow.

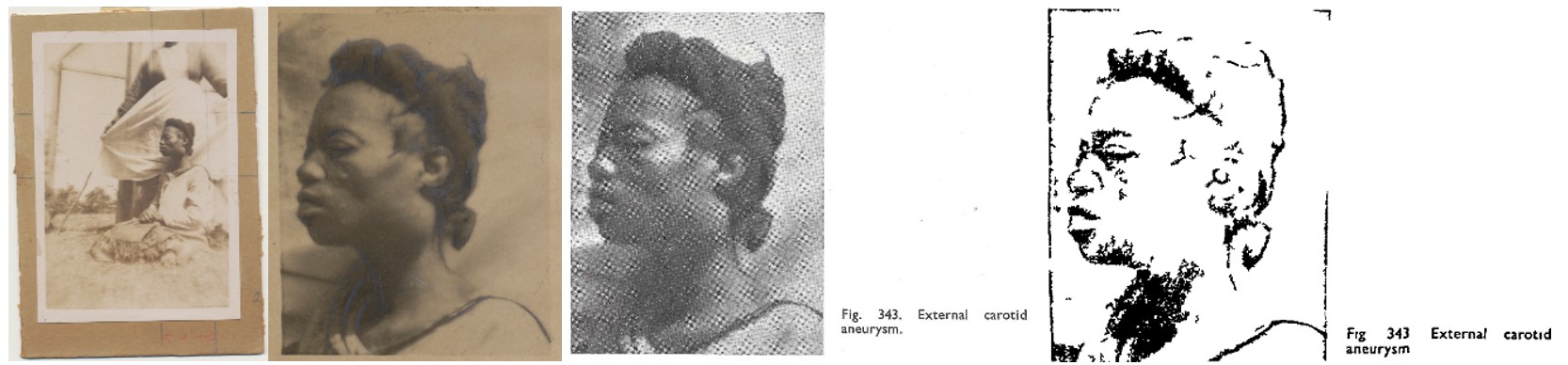

Various published and unpublished iterations of the same clinical photograph of a patient [Image Credit: UCT Pathology Learning Centre; John Wright & Sons Ltd.]

Framing clinical photographs as part of a broader network makes it possible to look across time, space, and social fields to see broad points of connection. The photographs were initially brought to Cape Town from abroad before being produced as teaching aids at South Africa’s burgeoning medical school. However, their operations extend beyond this original remit, opening new possibilities for both interpretation and use today.

Michaela Clark is a final-year PhD candidate at the Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester, UK. Follow her at @michaelaclarkba or via https://manchester.academia.edu/MichaelaClark.

Published: 04/28/2024