Dependencies out of place: the medieval horror of our times is but the shrapnels of the peripheral modernity

Giuliana Faccioli06/02/2024 | Reflections

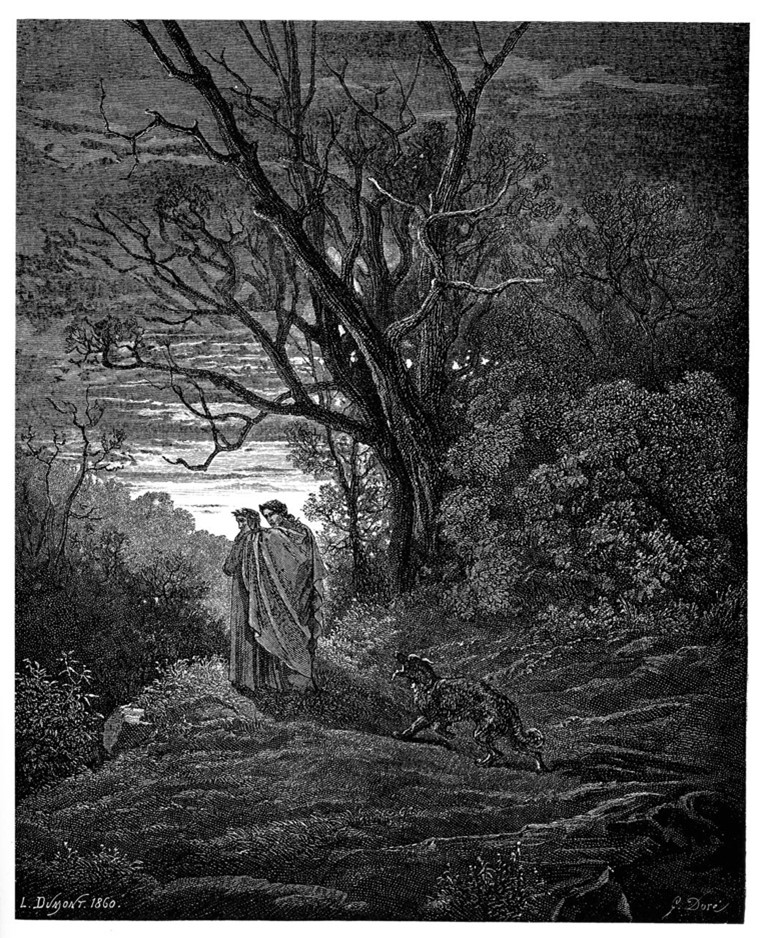

Figure 1: Illustration by Gustave Doré for Dante's Inferno [Image credit: Archive]

Will lead thee hence through an eternal space,

Where thou shalt hear despairing shrieks, and see

Spirits of old tormented, who invoke A second death”

– Inferno, Canto I by Dante Alighieri

“Capital is dead!”, cries out the winds blowing from the North. And from a gust they morph into a gale, as each day more and more voices join the choir of the latest trend in conceptualizing contemporary capitalism. The globalization and persistence of extreme inequality, generalized precarity, increased monopoly power, and regulatory deadlocks have caught the attention of Western intellectuals, prompting the rise of a new type of Reason – one that appears now under various names, such as Neo-feudalism, Techno-feudalism, Digital Feudalism, and Post-Industrial Feudalism. Advocates of this trend have emphasized that the pervasiveness of the digital has promoted a ‘Great Leap Backwards’, killing capital (as they have known it) and giving birth to a "new" past Europe. Neo-serfdom embodies the future of the labor market and monopoly platformization, the end of profits, with the coming of a new iteration of feudalism.

But the supposed novelty that surrounds such neo-feudal¹ hypotheses is only possible by omitting its true origins². In other words, here we are of the view that such proposition has not been able to disclose the real novelty behind major transformations as it has claimed to do once it ignored the relationships that capitalism has woven on a large scale throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. First of all, because it does not point to a fundamental change in the actualized capitalist mode of production – and thus, by what there is of concreteness in the abstract model. Secondly, because this concept already appeared in the first wave of neoliberal creative destructions at the beginning of the 21st century under the mark of Information Feudalism.

The term Information Feudalism was first coined to show how the privatization of intangible assets – enclosed by knowledge-based monopolies and backed by international pressure from the major high-income economies, especially the United States – could pose a major threat to the global economy as a whole. According to the authors, information feudalism was still unfolding, primarily through disadvantageous obligations imposed on developing countries under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which contained provisions on patents. As a consequence, developing countries (many of which had only been able to industrialize in the absence of a globalized IP regime) were constrained in their access to the most fundamental informational resources or found themselves once again having to comply to yet another round of drainage (through the payment of royalties) in order to access them:

"No one disagrees that TRIPS has conferred massive benefits on the US economy, the world’s biggest net intellectual property exporter, or that is has strengthened the hand of those corporations with large intellectual property portfolios. It was the US and the European Community that between them had the world’s dominant software, pharmaceutical, chemical and entertainment industries, as well as the world’s most important trademarks. The rest of the developed countries and all developing countries were in the position of being importers with nothing really to gain by agreeing to terms of trade for intellectual property that would offer so much protection to the comparative advantage the US enjoyed in intellectual property-related good." (Drahos & Braithwaite, 2002, p. 11)

The regulatory sovereignty of the Global South over its own scientific development was severely compromised by this neo-imperialist onslaught. After all, would it still be possible to incentivize investment in national innovation systems by relying on a patent-based R&D system? Or, more specifically, would an R&D system based on foreign ownership by private parties still be able to create an endogenous virtuous cycle or would it be bound to replicate that old pattern of external economies of developing countries? Once intellectual property rights put a price on information, the costs for states in the South to guarantee provision to their populations increases and the skewed pattern of income distribution is once again reinforced: only the upper classes become able to access the welfare provided by medications and other technologies that now become more expensive in developing countries.

As Drahos and Braithwaite (2002) have shown in the case of the dispute over antiretroviral drugs in South Africa, even attempts to break out of these bonds of international domination were met with a vigorous response. Subordinate countries were threatened with trade sanctions and pressured by supra-national entities (e.g. courts, banks, trade organizations) to enact specific regulations or to adhere to asymmetrical multilateral agreements³. Ultimately, the access to the gains in labor productivity was locked up in patents (owned by the big corporations in the core states) and therefore denied to the peripheral countries of the South. This would thus create a different framework for the social reproduction of capital on an expanded scale than had been seen before.

Picture 2: Pretoria protest march [Image credit: AP Photo/Christian Schwetz]

At the time, however, information feudalism was still an "incomplete project", that threatened to widen global income inequalities, provide monopolies with excessive profits, overtly increase the power of big business over government and hinder innovation. Low and middle-income countries were the biggest losers, but the process represented a potential hazardous to every other nation in the long term. From the perspective of the hitherto winners of this new regime, there seemed to be no doubt about the need for collaboration between knowledge-intensive corporations from the world's three strongest economies (Japan, Europe and the US) to restrict access to intangible assets in order to allow for the installation of production facilities where best suited them. The international nature of their production and the need to conquer new markets⁴ became the basis of this alliance.

However, rather than a global market with assured profits, what the US really sold to its European and Japanese partners was the image of a globally secure future for their innovations; ultimately, American companies still had more leverage to consolidate their position through the globalization of intellectual property standards. Still, “a world in which US corporations were dominant but European and Japanese corporations still remained powerful players was preferable to a world in which [they] faced competition from increasingly efficient developing country manufacturers."

In Cédric Durand’s work, Technofeodalisme, we can locate the maturing of this process, one in which the hardening of intellectual property rights has backfired (Durand, 2021) and can now be felt even in the Global North. Similarly, Jodi Dean’s Same As It Ever Was? also tries to point out a process of “reflexization, such that capitalist processes long directed outward – through colonialism and imperialism – turn in upon themselves.” In what way, then, does this feeling come to be expressed?

Patent laws may have hindered productive investment in innovation, but that hasn't slowed down the technological dispute, because even if corporations can't achieve an average profit on productive investments, they will be content to drive their capital in the search of at least the average interest⁵. In this way, it's not so much a distortion of competition as a sudden realization of its enduring presence for it lays bare the daunting feeling that yesterday's champions face the risk of becoming today's losers.

The unease with the profusion of “relations of dependence” that were previously considered incompatible, frictional or marginal to capitalism (such as expropriation, domination, and force) becomes even more evident: “Not even the barest fantasy of freely given consent accounts for the social relations of wealth accumulation today."

However, the inability to understand how these relations operate inside and “outside” capitalism (excluded from the market but not disconnected from it), guaranteeing its reproduction on an expanded scale, expresses an ideological image of ‘second degree’. In reality, the strong concentration and centralization of capital makes it possible to maintain control in dispersion, so that socially invisible forms ensure their functionality by deepening the forms that guarantee this very invisibility. Thus, by confusing invisibilizations with deaths, the neo-feudal narrative is doomed to always elaborate the present as a mere haunting.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Giuliana Faccioli is a Research Assistant for the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Time, Technology, and Capitalism (CIRTTC) at Concordia University, Montréal. She holds an MA in Social and Political Thought from York University, Toronto, and a Graduate Diploma in Latin American and Caribbean Studies from the same university.

__________________________

Endnotes:

[1] All “feudal” terminologies shall now be condensed into one by making reference to all of them through the “neo-feudal hypothesis”

[2] Here I am concerned with a historical transformation that served as a concrete basis for the emergence of this idea in recent times and not a subjective preference for a particular lineage of thought. Therefore, I contend that its origins lie beyond the genealogical conceptualization drawing from the Habermasian ‘re-feudalization of the public sphere’ like other authors have opted to pursue (see: Neckel, 2021; Morozov, 2021; Durand, 2020)

[3] Any resemblance to Jodi Dean's idea of parcellization of sovereignty is no accident.

[4] Not just a need, but a coercive law – although not one of legal nature, but of reproductive necessity.

[5] Not by accident, 21st century capitalism has multiplied the forms of interest-bearing capital associated with communication and information technologies.

Published: 06/03/2024