Regulating Generative AI Threats and Social Commons in the Public Interest

Author: Sarah Cheung (University of Edinburgh)Editor: Catriona Gray (4S Backchannels, Global North)

08/26/2024 | Reflections

Since OpenAI’s ChatGPT was released publicly in late 2022, generative AI models (‘genAI’) have achieved considerable public salience. They have showcased AI’s abilities to create novel content akin to that produced by humans – with their technical advances surprising even some experts in the field and adding grist to ongoing global deliberations around AI regulation.

Existing regulatory approaches, such as that of the European Union, typically strive to attain a balance between AI’s assumed risks and benefits, in the pursuit of societal good (or other synonyms to denote the public interest). Robust understandings of these potential harms and benefits are required, then, if we are to regulate generative AI threats effectively. After all, it would be hard to ‘act’ on something without some idea of ‘what’ it is we are dealing with.

The wide availability of myriad genAI offerings, from Microsoft-backed ChatGPT to key rivals Claude and Gemini (previously Bard), has given rise to extensive opportunities for their use by the general public (including embedding them into commercial applications such as Microsoft’s Copilot, Apple’s ‘Apple Intelligence’, or Google’s Gemini), and thus provided initial clues as to ‘what we are dealing with.’ There was shared amusement at farcical interactions with chatbots: Meta’s own chatbot claiming that Zuckerberg’s company ‘exploits people for money’ or the absurdity of a lawyer submitting a brief that included made-up cases, because he used a chatbot to do his homework. Even Microsoft, the world’s most valuable company and key leader in the AI field (also OpenAI’s largest investor) has not been immune to AI’s penchant for ‘confabulations,’ having named a foodbank as a top tourist attraction in Canada’s capital city in a travel article.

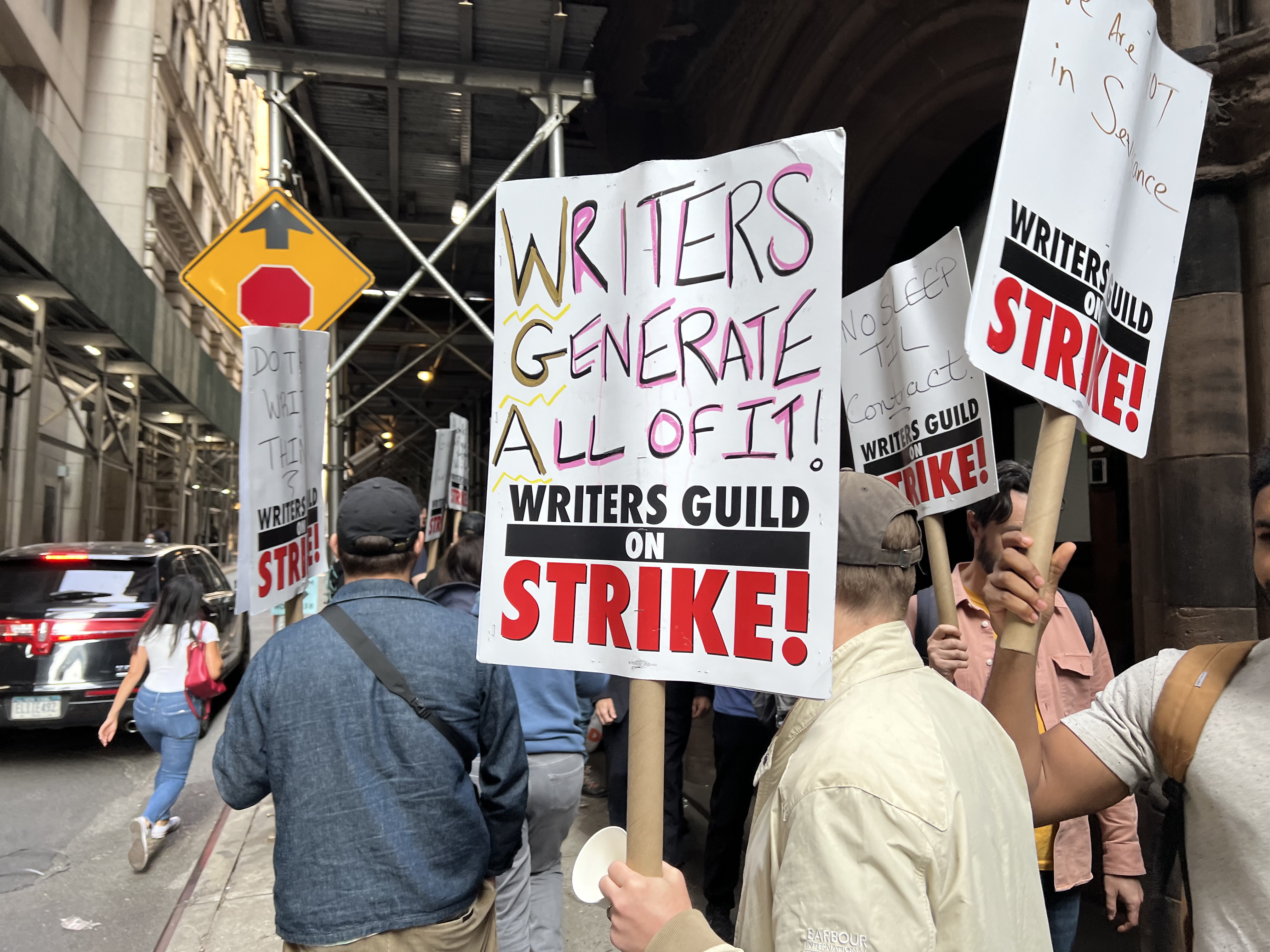

(Writers Guild of America 2023 writers strike. Source: Fabebk CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

But there has also been fear and dismay at AI’s potential harmful impacts: from students cheating on assignments, to the dangers posed to vulnerable people, and concerns of mass job losses. One major German publisher’s plans to replace a swath of editorial roles with AI was another blow to a press industry that has already been crippled by the rise of digital giants and their products. Elsewhere, the recent Hollywood writers’ strike was motivated by concerns over use of AI in scriptwriting, while the actors’ union likewise sought safeguards over the use of actors’ likeness in AI-produced content. Alongside these concerns, purported ‘existential’ threats of human extinction also made for attention-grabbing headlines. Given such concerns it is perhaps surprising that several, if not all, of the Big Tech leaders are still pursuing AI development at break-neck speed. This has led critics like Meredith Whittaker to pose the question: these developers can pause – so if the tech is potentially so harmful to society, why don’t they?

The obvious refrain typically provided is that AI can still provide lots of benefits to society: from improving cities, supporting healthcare and other scientific advances, reducing inequalities, to tackling climate change. In short, the aim is to keep the shiny tech baby and throw out our unwanted dystopian bathwater. Apparently, regulation can help on this balancing act – see for example the UK Government’s moves in late 2023 to establish a public entity explicitly tasked with ensuring AI safety in the public interest. Yet both ‘the public’ and its ‘interests’ are notoriously tricky to pin down: there is the perennial problem of establishing who or what counts as the public (or even if there are multiple ‘publics’) and its interests. Meanwhile, how we might understand those types of digital resources we share or use in common can run the gamut from digital public goods to critical gatekeepers. Exactly what notions of ‘public(s)’, and their ‘interests’ are deployed within legislative process are crucial, as ambiguities over what counts as the ‘public benefit’, ‘social or common good’, may serve, as I have argued in my own work on public health data, to legitimate specific activities using these digital technologies.

Stepping back from prominent dystopian visions to consider the nature of (other, more mundane) possible risks from widespread AI uses, we see that the examples above (e.g., AI’s effects on the press and filmmaking industries) point to the role of content creation in our increasingly digitally mediated social commons. As critical digital scholars have often noted, the digital commons does many things. It is our digital public sphere, the so-called ‘marketplace’ of ideas, and serves as a site of social interactions. In this way, it fulfils our need for social connection (‘social capital’, in the Putnamian sense). Beyond this space of sociality, it is also a site of general knowledge creation. Interdisciplinary critical scholarship has made clear that, as the digital realm increasingly becomes the dominant source of knowledge creation, a new algorithmic epistemology becomes our dominant epistemology.

While the impacts of these new types of digital epistemology on bias and discrimination on members of vulnerable groups have been well noted (see, e.g. the work of Eubanks, Browne and O’Neil), in regulatory approaches these impacts have typically been viewed on the basis of individual rights. This is a good start, but perhaps not enough if we don’t wish to simply conceive of public interest as an aggregate of (Benthamite) individual interests. It is worth returning to critiques of ‘the platform’ – that key intermediary of our social interactions – to consider how genAI may contribute to social impacts on a broader, communal dimension. Under Habermas-inspired ‘public sphere’ critiques, platforms (and their associated AI) have long been a threat to deliberative democracy, due to their capacities to systematically reshape our social reality/ies along instrumental logics (typically seeking profit and/or control). These processes in turn undermine our ability to exercise independent rationality in a ‘lifeworld’ outside economic and political systems. (We are already familiar with how misinformation and disinformation online by ‘bad actors’, or even unaware individuals, contribute to this.) Generative AI brings another dimension to this familiar critique. By jettisoning what is now superfluous, generative AI is not cutting out what was the middleman (the intermediary platform). It instead cuts out the human. We engage with programs and applications that simulate (or mimic) a human or human activities, without one being present. Instead of just filtering and distorting our relations with each other and our world, those others are now increasingly sidelined.

The Habermasian theorization of the public sphere, public interest, and democracy is just one approach to conceiving of what ‘a public’ or ‘social commons’ involves, and what sustains or damages it. We may prefer to use another while, at the same time, recognising that the deliberative and participatory commitments it espouses are key ways we typically expect to go about choosing between alternatives. Either way, we need to be upfront about what we believe that ‘public’ is, and what we wish it to be, before we regulate in its name. Recentring a shared social commons into considerations of ‘public interest’ allows us to foreground substantial questions over the logics of profit: Who gets to profit from this space and resource? How do we prevent everything in social life being subsumed into the logic of surveillance capitalism? While messier and more mundane than the imminent demise of humankind, concerns with our present, shared social existence ought not be sidestepped in efforts to regulate AI in the public interest.

Published: 08/26/2024