Can science ensure “100% Halal”?

Author: Arum Budiastuti (Airlangga University, Indonesia, and University of Sydney, Australia)

Editor: Auriane van der Vaeren (4S Backchannels)

10/07/2024 | Reflections

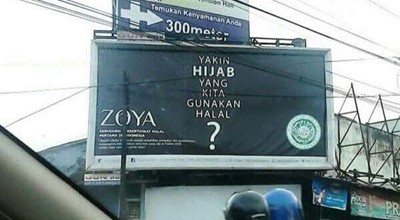

In early 2016, a popular Muslim clothing line in Indonesia, Zoya, launched a billboard advertisement on major streets across Java featuring a provocative tagline alongside a halal logo (Fig1):

“Yakin hijab yang kita gunakan halal?”

(Are you sure the veil we wear is halal?)

At first glance, viewers might have assumed that halal in this context referred to the concept of modesty in dress. Yet, Zoya’s explanation on its Instagram account (@ZoyaLovers) surprised many: as is the case with food, halal here too meant the absence of alcohol and porcine elements in the manufacturing process.

The ad sparked controversy because halal marketing for non-food commodities based on the fear of pork and alcohol contamination was unprecedented. Today, however, more brands are offering halal non-foods, such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, or home appliances like refrigerators. Scholars have described this growing trend as halalisation, halalification, or pan-halalisation. This, I believe, is enabled by technological innovation that pushes the boundary of enacting halal. The question then is: to what extent can a product’s halal status truly be verified? Namely, can modern science ensure that something is 100% halal, and what are the implications of such ambition? This post attempts to answer these questions while alluding to the challenges of navigating everyday religious practices through technological fixes.

Halal and Technology

Halal, which means lawful or permissible in Arabic, is a regulation on the proper Islamic way of life. Food-wise, halal includes all types of food except those mentioned as haram (prohibited) in the Qur’an: pork, spurting blood, khamr (alcoholic beverage), and animals not slaughtered in God’s name. In the past, the halal status of food relied on mutual trust between consumers and local producers, especially in close-knit Muslim communities that shared religious and cultural values. Traditionally, in case of doubt on the origin of the product and on whether to consume it, Muslims relied on their own judgment. This came to a change with the industrialization and globalization of the halal food industry.

With the expanding global halal industry—estimated at US$3.2 trillion for 2024 with a 5.2% annual growth rate—came an increase in fraudulent halal practices, such as fake halal labels, or the use of pork substitutes or prohibited ingredients like pork intestine casings. Even in seemingly innocent products, like confectionery, porcine gelatine is found but undeclared. As Muslims grew concern over the authenticity or purity of supposed halal foods, halal assurance now became provided by third-party certification bodies. Notably, these bodies use advanced technologies to certify the absence of any haram material.Beyond food products, pig derivatives are also found within a vast number of daily objects such as paint, brushes, and personal hygiene products. These products are thus considered najasa (impure). To test against pig contamination, the two main speciation methods currently in use are protein- and DNA-detection analyses. DNA testing is the preferred method as it is more reliable to detect the potential contamination of processed foods. A portable DNA toolkit has even been developed for consumers who would like to detect any porcine material in food (Fig2).

Fig2 A portable DNA kit to detect the presence of pork in food products invented by a French start-up biotech company

Aside from direct contamination, there are cases of cross-contamination between haram and halal ingredients, such as in manufacturing sites which produce both halal and non-halal food items. The fear of cross-contaminations in the food-processing chain and the food-supply chain has brought technology-enabled halal certification to a whole new level. Namely, it made room for traceability requirement; that is, the ability to track food and food ingredients from producer to end-user to ensure that the product is free from any contact or activity—whether intentional or not—that may violate halal status.

Recent supply chain technologies, such as Blockchain and RFID (Radio Frequency Identification), play an important role in materialising this goal. Strict product segregation—from procurement, to transport, to product display—is designed to ensure that purity is maintained through and through. The system not merely seeks to ensure an item is "halal" but makes the promise it is "100% halal".

"100% Halal": Are we missing the essence?

Halal labels help Muslims choose food in accordance with their faith, especially in places where they are a minority. The integration of advanced technology has brought more confidence toward these labels. For some, similar to the organic food market, the stricter the certification process, the better—especially when the price remains competitive. For this reason, the quest for "100% halal" seems to have the wind in its sails.

This technology-enabled trend, however, challenges the traditional Islamic principle in food consumption whereby permitted food is presumed halal. According to some historical accounts, the Prophet did not ask for food to be "100% pure", as in absolutely free from any impurities, as this achievement is impossible to ascertain in absolute terms . With modern halal certification, everything is considered haram—unfit for consumption—unless proven otherwise. Not only does this change the meaning of halal, it also affects the way Muslims relate with others. A Muslim woman for instance refused to eat a meal prepared by her friend because the cooking cream used was not certified halal. This case is significant, because in the traditional halal way of life, niyyat (spiritual intent) and visible signs of Muslim identity are considered a secure basis for living halal. Now, with technology-based halal certification, the halal practice has shifted from a focus on spiritual intent to a greater emphasis on material purity.

The technological-fix approach in modern halal certification also glosses over urgent ethical and environmental problems, such as greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption in the halal industry, or animal abuse in slaughterhouses. For instance, during my fieldwork, I encountered cases where cows were doused with excessive amounts of water before being weighed for sale. Although grassroot movements striving for ethical and sustainable halal practices exist, these efforts currently lack the amplification needed to influence the industry practices. Clearly, there is much work to do, especially considering the halalification of commodities other than food. In essence, halal certification practices may not remain confined solely to material concerns.

Arum Budiastuti is a lecturer at the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Airlangga (Indonesia). She is in her final PhD year at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney (Australia). Her research interests include material culture, food studies, religion and culture, and STS.

Published: 10/07/2024