Excremental Hauntings, or the Waste of Modern Bodies

Author: Warwick Anderson (University of Sydney, Australia)

Editor: Auriane van der Vaeren (4S Backchannels)

11/04/2024 | Review [*]

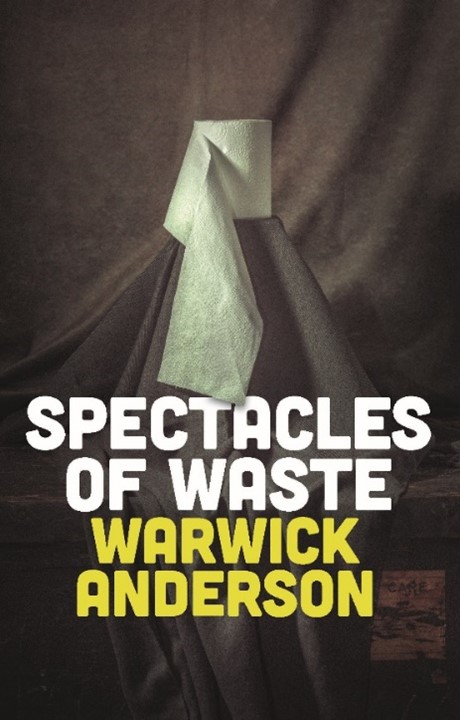

As I was writing Spectacles of Waste (Fig1), I got the feeling that a specter is haunting the modern world. Not the specter of communism, alas, but phantom human excrement, the uncanny stool. In keeping with the book’s title, I suppose I should say it is an increasingly spectacular, if disagreeable, specter.

I’m referring to the apparition shadowing most of us as we attempt to go about our modern hygienic lives – an eerie presence that we virtuously insist must be absent, either flushed away into oblivion or magically refigured and replaced by secure data sets and models. The dirty abject stuff that we seek constantly either to remove and deny or inscribe and sublimate. We “civilized” moderns develop all kinds of techniques and infrastructures and incantations to render shit invisible – yet it keeps returning, so it seems, to bite us in the bum. Thus, relentless expulsion and rejection of our intimate excretions – what Friedrich Nietzsche in Genealogy of Morals called “the pathos of distance” – ultimately proves unsustainable. Or as Bruno Latour told us, we have never truly become modern. But how we keep trying.

Late last century, inspired by the fashion for histories of the body, I expatiated on what I called “excremental colonialism” in Critical Inquiry – in an article now cited some 400 times thanks to scatology’s enduring appeal. I described the obsessions of early twentieth-century white American health officers with Filipino defecation. These white men presented themselves as purely expressive, retentive, controlled – whereas the Filipinos they had colonized, or rather colon-ized, appeared as “promiscuous defecators,” primitive voiceless polluting figures requiring ceaseless surveillance and reformation. I wanted to show how U.S. colonialism in the Philippines was intimately embodied, how it came to constitute a racialized orificial order, marking a somatized hierarchy of closure and control. The essay prompted a minor excremental deviation in science and technology studies, towards “excremental postcolonialism,” “excremental posthumanism,” and my own brief return to “crap on the map” in the Philippines after its ostensible independence.

My inquiries into colonial wastes and their alleged superfluity caused me to delve deep into social theory and cultural anthropology, as have many other STS scholars. I immersed myself in the symbolic dimensions of medicine and public health. Heeding William James’s warnings against “medical materialism,” I realized, despite my own medical training, that scientific explanation will not completely substitute for symbolic import or spiritual significance. Indeed, most efforts to render shit epidemiologically legible have exerted a symbolic or irrational compulsion out of proportion to any actual utility (Fig2).

But for a few decades after those initial speculations on excremental colonialism, I managed generally to resist the fecofugal spin. Then came COVID-19 and the surge in interest in wastewater epidemiology. In societies where individual testing and contact tracing are possible, this seems to me a largely redundant technology. Yet we were transfixed. It was a vivid example of the implacable return of the human stool to the biosecurity calculus. So, I wondered, how do we understand this incapacity to leave behind the defecatory scene? What is happening when we imagine otherwise worthless, even dangerous, human wastes as informative and valuable viral sentinels? What biomedical rituals make this transformation happen?

I decided, perhaps rashly, to write Spectacles of Waste. As I did so, I greatly expanded my excretory range, encompassing not only wastewater epidemiology but also the fecal obsessions of psychoanalysis, social theory, modernist literature, recuperative anthropology, and “shit art.” The middle passages of the book channel us back to the racial colon-izing of the body, including self-colonization, and the encroaching Latrinoscene – that is, the Rockefeller-led building of millions of pit toilets from the 1920s, transforming the planet. I considered fecal fetishes, defecation as a labor process, toilet paper as the original inscription device (hence the run on it at the beginning of the pandemic), and the disruptive proliferation of uncanny or phantasmatic stools. I returned to the scientific datafication and sublimation of excrement, manifested in the proliferation of investigations of the human gut microbiome, where waste is transmuted into millions of molecularized “gut buddies.” I think of the book’s contents as a scatological ensemble, a rich fecal palette, a feast of ordure. According to Anna Tsing’s kind endorsement, I put “the ‘anal’ back in analysis, and the ‘colon’ back in colonization.” (At least I hope she meant it kindly.)

We are assured that as wealthy moderns we might safely evacuate our wastes, keeping them at a distance, purifying them. But these days, as our sanitary infrastructure decomposes, simply flushing rarely feels sufficient. Residual anxieties about excrementitious stuff haunt us, threatening us with abjection, driving us to double down on securitizing our waste through rendering it safely molecular and data rich, even when practical benefits are few. Enduringly fascinated by defilement, we keep finding ways to represent safely the unspeakable, to make the abject a securely distant, yet spectacularized, object – hence, codifying wastewater epidemiology and the gut microbiome. As Roland Barthes pithily put it: “Shit has no odor when written.”

Fig3 The implacable return of excrement: matter out of place? (credits: art installation by Helvetas in Zürich for World Toilet Day; Merkur.de 19 Nov 2013)

In a sense, then, colon-ization, whether of self or other, has become the decolonial limit experience, the rule we cannot imagine breaking. To think with rather than against the colon would be to deny our “modern” identities. (If Latour had been less prudish, he may already have considered this embodied interiority of not truly being modern.) Can we imagine modern life outside the dialectic of the sphincter – which is the corporeal form of the dialectic of Enlightenment? (Both Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno were fixated on anal character, after all.) We feel the need to reassert conventional structural binaries: hygienic or dirty, civilized or natural, modern or primitive – with the first term of each juxtaposition privileged. We seek to expel or sublimate whatever might trouble these boundaries. We prefer scatologics to eco-logics.

Since I finished Spectacles of Waste, our excremental anxieties have only grown in intensity. As Steve Bannon recommends, we’ve flooded the zone with shit. The Seine is supposedly full of poo. Sewage systems are breaking down and overflowing across the developed world. Turds are catching waves in England; Eton College closed when its toilets blocked. In a 2023 debate between U.S. governors Ron DeSantis and Gavin Newsom, DeSantis proudly displayed the San Francisco “poop map,” plotting some 250,000 reports of human feces deposited on the city’s streets. It was a means of colon-izing the homeless in California, degrading the progressive state, and signaling its lack of manly Republican (retentive) virtue. At a dinner in 2024, former president Donald Trump, who deplores non-white “shithole” countries, told supporters he will never again use the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office because Joe Biden had “soiled” it. I could go on: the profusion of poo museums around the world; new panics about “toilet plumes”; the incredibly popular YouTube series “Skibidi toilets” (viewed more than 65 billion times); celebrity American proctologists or “bottom whisperers”; Wim Wenders’ film Perfect Days set in high-modernist Tokyo toilet blocks; prisoners performing “dirty protests” in the Philippines against president Rodrigo Duterte—the list is endless. A burgeoning sense of widening permeabilities and porosities, the prospect of immunological failure, the looming specter of fecal peril—these anxieties, these hauntings, have made the spectacle of shit, and its containment or sublimation, more compelling than ever.

We even have a new word for the Fecoscene, our characteristically amodern condition: enshittification. Coined a few years ago to describe the decay of internet platforms, the term was soon expanded to include the multiple ways in which contemporary capitalism destroys human dignity. “The obscene little word did big numbers,” its creator Cory Doctorow said, “it really hit the zeitgeist.” You see, that’s just what I mean: a specter is haunting the modern world …

[*] An earlier version of this contribution appeared on the website of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in July 2024. Thanks to Louise Edwards and Abra Pressler for helpful suggestions.

Featured image credits: Allison Robbert for The Washington Post, October 24, 2024

Warwick Anderson is Janet Dora Hine Chair of Politics, Governance and Ethics in Health, located in Anthropology and the Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney. Additionally, he is an honorary professor in the School of Population and Global Health at the University of Melbourne. He has written on science, race, and colonialism; medicine and whiteness; postcolonial technoscience; prion diseases; autoimmunity; disease ecology and planetary health. In 2023, he received the John Desmond Bernal Prize of the Society for Social Studies of Science. He is currently building courage to write another book, tentatively titled Spaceshit Earth, about waste and efforts to contain it in the Cold War.

Published: 11/04/2024