Bee smellscapes: olfactory relations in urban everyday ecologies

Ceall Quinn11/11/2024 | Reflections

Figure 1. Female metallic green sweat bee (Agapostemon subtilior) chewing stamens to collect pollen from fragrant lacy phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia) on the Arbutus Greenway, Vancouver, Canada. Photo by author.

While the urban is often withdrawn from ecological imaginaries, attending to city smellscapes has the potential to restore a felt sense of multi-species co-habitation, or, an attunement towards the diverse lifeways that compose the pulse of shared place. The city is an accretion of human and nonhuman processes. In Vancouver [Canada], we find a gathering of climate, geology, biology, coloniality, imagination, economy, development, migration, and more all mixed up in the present and contested visions of the future. Can olfactory approaches reconfigure the ways ecological imaginaries interface with the urban? How might attentive scent practices invite a conscious registering of the more-than-human everyday? What can smellworlds tell us about how pollinator relations unfold in urban ecologies? And, what would it mean to assert a multi-species ‘right to the city’ (Lefebvre, 1996)?

The above is a revised excerpt from a smellwalking zine I crafted as part of a workshop I led for DoingSTS. DoingSTS is a methods lab that combines feminist science and technology studies and affect studies through inquiry into ordinary practices. This passage effectively sets up themes I wish to highlight in this blog entry: the ways olfactory ecological relations form in cities and the possibilities scent methods open for attuning to more-than-human worlds. I begin by discussing my zine and smellwalking workshop; then, I elaborate on multispecies smellwalking as a methodology. Finally, I conclude with a discussion of pollinator relations in urban space.

Workshopping a pollinator smellwalk

The zine was part field-guide, part map, and part methodological orientation. Zines as DIY (Do It Yourself) publications offer an informal and inviting means of sharing scholarship. Complete with a centerfold for note-taking, I used collage to piece together diagrams of bee life cycles, smell words, and instructions for tincturing. Materials from this zine were subsequently published in a chapter contributed to Everything Is a Lab (2023) and presented at the 2023 annual 4S conference in Honolulu.

Figure 2. Back/front of Pollinator Smellwalk zine. Drawings of blue orchard mason bee (Osmia lignaria) (left) and male green metallic sweat bee (Agapostemon subtilior) (right) by author.

During the workshop we walked a stretch of the Arbutus Greenway, a ‘rails-to-trails’ pedestrian and bike path converted from the old Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) corridor. Purchased by the city in 2016, the land the Greenway now sits on has been a site of contestation between the city of Vancouver and the CPR for decades. While concrete now paves over industrial legacies of Vancouver, the Greenway’s curved arc discloses its ever present past. Truman and Springgay (2018) identify these efforts to “re-naturalize de-industrialized space” (p. 31) as ‘landscape urbanism.’ However, they caution against an uncritical celebration of greenspace, citing the dangers of “racialized, classed, ableist, and heteronormative ideologies that co-opt conservation in order to ‘clean-up’ and ‘push out’ different populations, or maintain settler colonial heteronormative elite spaces” (p. 31). As we walked, we discussed the ways that private gardens alongside the path provide habitat and forage for pollinators, while also potentially reproducing the regulative function of landscape urbanisms.

Referencing the zine, I gave brief primers on bee and floral life histories as we traversed our route and, emphasizing our collective practice, invited participants to contribute their knowledge, sensations, insights, and questions. The rhythm of smellwalking is punctuated by pauses. Stopping to smell flowers allowed us to also consider their morphological characteristics and pollinator relationships, such as the way liquorice-scented fennel’s (Foeniculum vulgare) flowering umbels articulate with the short brush-like tongues of masked bees (Hylaeus sp.). We ended our walk at Maple Community Garden where I passed around tinctures I made from flora gathered throughout the season. We played with a vocabulary for capturing the sensations and associations evoked by scent—smellwords like resiny, herbaceous, pungent, dank, green, acrid. As preserved records of the timespace of floral encounters, smell tinctures can be understood as archives of place.

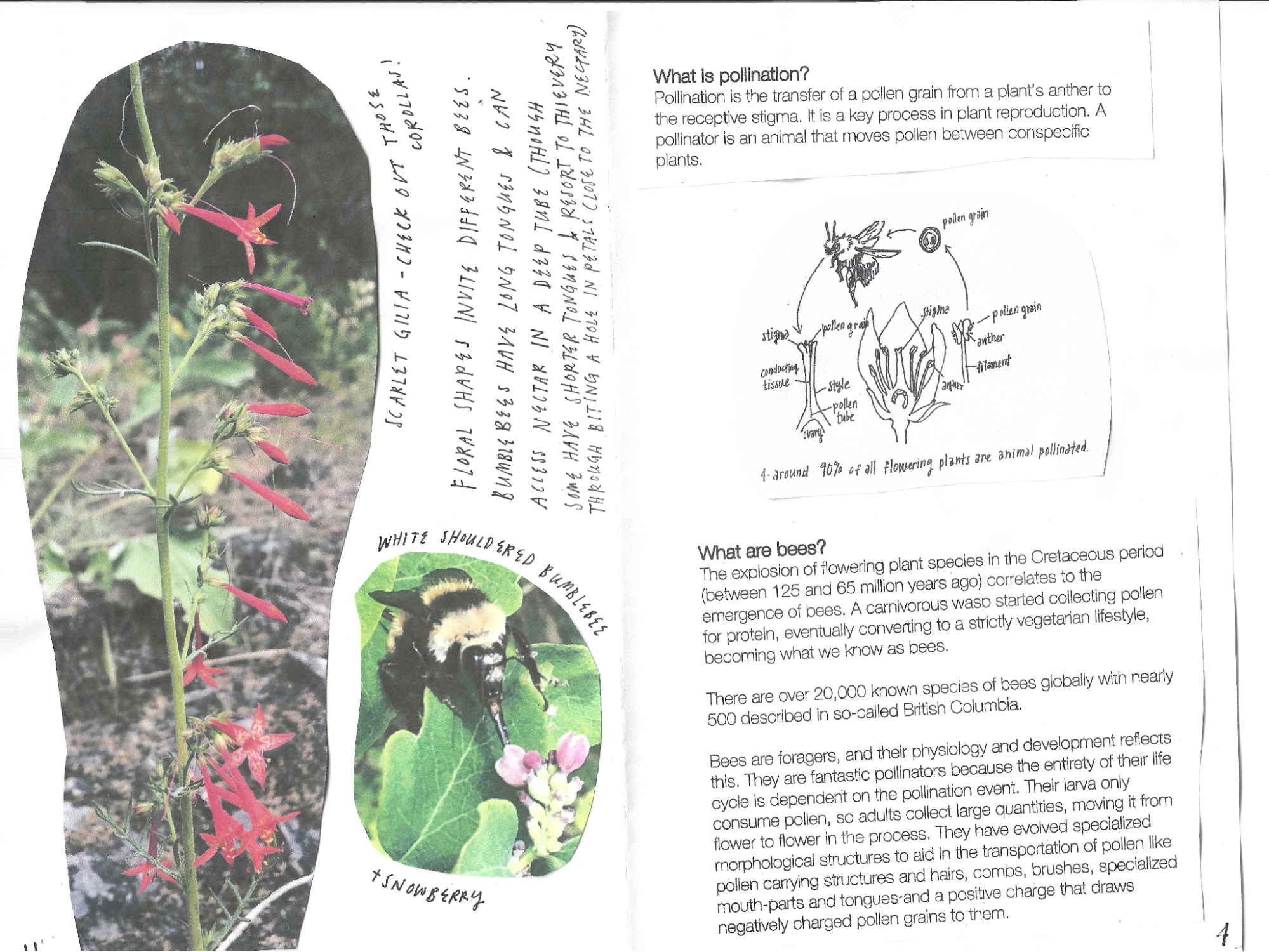

Figure 3. Pages from the zine discussing the relationship between floral shapes and bees and a gloss of pollination and bee evolutionary and life history.

The workshop was designed to open up a speculative space for considering how the urban is sensually constituted as “a living formation” (Barua, 2023, p. 1). In other words, urban spaces are not only human spaces but also composed of ‘beastly places’ (Philo and Wilbert, 2000) in which a multitude of species make their lives. Participants were invited to share in everyday practices of collective walking, focalized through attention to pollinator smellscapes.

Figure 4. Masked cellophane bee (Hylaeus sp.) on licorice-scented fennell (Foeniculum vulgare), Arbutus Greenway, Vancouver, Canada. Photo by author.

Multispecies smellwalking: practicing smellwalking and multispecies ethnography

Multispecies smellwalking is guided by two interlinked methodologies: smellwalking and multispecies ethnography. A smellwalk is a practice that takes the attentive capacities of mindful walking—“an interactive way of knowing, allowing the entire body, and all of its senses to experience the surroundings” (Jung, 2014, p. 625, emphasis in original)—and concentrates on smellscapes, or, the ways scent inheres, emanates, lingers, and disperses across geographies. On her group smellwalks across the United Kingdom, Victoria Henshaw (2013) inquires after “the smells that people can detect, what they think about them, how these change between places and how the built environmental form and component parts influence the urban smell experience” (p. 45). Paying attention to scent discloses politics that infuse the urban: for example, class stratification, imaginaries that animate decision-making, and, in our case, landscape urbanisms.

My aforementioned workshop supplemented smellwalking with the sensibilities of multispecies ethnography, defined by Ogden, Hall, and Tanita (2013) as “ethnographic research and writing that is attuned to life’s emergence within a shifting assemblage of agentive beings” (p. 6). Taking a cue from Myers (2020) we practiced using our bodies as sensing instruments, considering sensorial difference across species lines. Multispecies smellwalking as a methodology isn’t reducible to the direct apprehension of smell; rather, it is a practice tied to the speculative imagining of the sensory worlds of urban bees and their olfactory relations to the urban surround. I asked participants to regard how urban bees navigate urban environments, and how, in considering this question, cities and their inhabitants might orient towards hospitality through projects that enhance connectivity and prioritize the seasonal provision of forage and habitat. Van Patter (2022) writes: “More expansive and generous modes of seeing the city can open space for radical and inclusive knowledges and practices for urban life” (p. 925). Multispecies smellwalking, a practice for smelling the city, is one method for opening up this speculative and practical space in pursuit of better pollinator relations within the urban.

Figure 5. Yellow-faced bumble bee (Bombus vosnesenskii) nectaring on sea holly (Eryngium spp.), a plant redolent of cat urine at Fifth and Pine pop-up park, Vancouver, Canada. Photo by author.

Urban olfactory relations

Bees antennae are multi-purpose sense organs. They are covered in thin hairs called sensilla, which are used in olfaction, or “the sensing of air-borne chemicals from a distance” (Chittka, 2022, p. 43), along with mechanical and gustatory reception. Scent markers play important roles in bee life histories including: aiding in locating nesting sites, facilitating nestmate recognition in social bees, and the subterfuge strategies of cleptoparasitic bees that mimic the chemical signals of their hosts, enabling them to enter nests unnoticed. Flowering plants and pollinators, especially bees, are entwined in a millions of years old “ancient coevolved partnership” (Danforth, Minckley, and Neff, 2019, p. 289). Through their morphological forms, colors, and the emission of volatile organic compounds, plants create lines of communication for their pollinator partners and adversaries. In their involutionary reading of chemical ecology, Hustak and Myers write: “It is this volatility that gets read as a kind of vocality, a way of speaking in a chemical vocabulary” (2012, p. 100). Keeping in mind the sensory worlds of bees and their flowers while smellwalking, we can begin to notice how different species make their lives in relation to one another in the city.

While urban environments with vast concrete expanses, patchy floral distributions, and heavy disturbances pose a challenge for bees, some species persist and even thrive in city spaces. Multispecies ethnography is a practice of honing “arts of noticing” (Tsing, 2015, p. 37), or, developing attentional capacities for tuning in to multispecies presence, rhythms, and spatio-temporalities. In the spring, upon emerging from hibernation, bumblebee queens seek cracks and crevices to establish a new colony. They do not excavate their own nests, instead seeking pre-existing cavities, with deserted rodent burrows constituting prime sites. In their experiments in baiting bumblebee nest-boxes with rodent odorants, Varner et al. (2023) found that boxes baited with odorants had a much higher occupancy rate than unscented boxes. This research suggests that pungent rodent scents—their excrement, sex pheromones, bodily detritus—act as critical lures for bumblebee queens navigating in search of nesting space. Thinking and imagining across species sensorial difference enables a variation on the urban to emerge where hollows become the possibility of a home, rodent odorants cues for generational ongoingness, and the presence or absence of flowers for forage a question of life or death.

Smellscapes in the city are redolent of entangled lifeworlds. Attending to the olfactory invites a consideration into the more-than-human relations that constitute the life of cities. I see multispecies smellwalking as a starting point from which to keep building, thinking, and gathering together with “earth others” (Plumwood, 1993, p. 137), and I invite you, if you’re not already doing it, to partake in this practice—to build attentional capacities, and, if inspired, to help create more hospitable relations with pollinators in urban space.

Author Bio

Ceall Quinn is a PhD student in (more-than) human geography at the University of British Columbia. He studies political ecologies of pollination, urban meadow making, and multispecies rhythms in the city. He can be contacted at: acquinn93@gmail.com.

Editor's Comment

Richard Fadok edited this post.

Footnotes

[1] Danforth, Neff, and Minckley (2019) show that while urban environments seem to favor “[c]avity nesters, host-plant generalists, and invasive species,” this isn’t a “hard-and-fast rule” (p. 352). For instance, while pollen-specialist bees are generally sensitive to urbanization, their populations can persist so long as their host plant occurs in urban settings (see Cane et al., 2006).

Published: 11/11/2024