Possession as Ruse—A Conversation about Digital Dispossession

Nanna Bonde Thylstrup and Fleur Johns12/09/2024 | Reflections

Lacework, action: cheering, attribution to the original source has been broken here by the dataset construction process of Moments in Time, but file name yt-I3071WuqgTs_250.mp4 (at the bottom of the video) gestures at where it was initially scraped from. [Image credit: Everest Pipkin's Lacework ]

“Nothing is yours. It is to use. It is to share. If you will not share it, you cannot use it.”

― Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974)

Many modes of dispossession apparent in the global digital economy are not well understood by tracking the possession of things, data, land, or some forms of legal right. Possession and deprivation of possession are often not necessary for the exercise of control or the extraction of value in prevailing techno-economic infrastructures. This dialogue between Nanna (a scholar of critical data studies, cultural theory, and STS) and Fleur (an international legal scholar) explores how exploitation is transformed in and by emerging data economies and probes how scholars might take account of this transformation when researching in STS and adjacent fields. This conversation emerged from Fleur Johns' lecture "Digital Humanitarianism" at the University of Copenhagen, delivered as part of Nanna Bonde Thylstrup's research project Data Loss: The Politics of Disappearance, Destruction and Dispossession in Digital Societies. (funded by the ERC) The event, moderated by Dr. Amir Anwar (University of Edinburgh), sparked a rich exploration of dispossession's conceptual possibilities and constraints.

Recent developments in digital economies have made urgent the need to rethink traditional frameworks of possession and ownership. Take, for instance, the 2023 controversy over OpenAI and other tech companies using publicly available data to train large language models without clear consent or compensation. These controversies point to broader issues related to machine learning reuse economies and their complex reconfiguring of relations between access and control, data and algorithm.Or consider the increasing precarity of gig economy workers who, while technically "independent contractors," find themselves bound by opaque algorithmic management systems that control their labor without direct employment relations. Similarly, the rise of subscription-based digital services has transformed ownership into temporary access rights sometimes even severing the relations between creators and works, while social media platforms simultaneously encourage "sharing" while maintaining strict control over user-generated content and its monetization. These examples point to a fundamental shift: in today's digital economy, power and profit often operate through control mechanisms that don't require traditional forms of ownership or possession at all. As these changes accelerate—from AI training practices to platform labor relations to digital rights management—we find ourselves increasingly ill-equipped to address new forms of exploitation using conventional frameworks of dispossession.

Action: Balancing. Attribution to the original source has been broken by the dataset construction process of Moments in Time, but file name iddv890015_1.mp4 (at the bottom of the video) gestures at where it was initially scraped from. [Image credit: Everest Pipkin's Lacework ]

FJ: Each of us has experienced dissatisfaction or ambivalence with the register of dispossession as a way of grappling with exploitation in global digital economies. And the changing valence carried by the epigraph above from Ursula Le Guin’s 1974 anti-capitalist, anti-war, anarchist novel seems to capture nicely the shifts that dispossession does not fully capture, so let’s come back to that. To kick us off, though, perhaps we might say something about what the discourse of digital dispossession does illuminate.

For my part, I think back to David Harvey’s reworking of Rosa Luxemburg’s and Hannah Arendt’s analyses of the dual character of capital accumulation⎯as involving linked processes of, first, expanded reproduction and, second, forceful extraction from an “outside” that capitalism continually creates. It was, I think, valuable to dispense with the idea of the second as a “primitive” stage directed solely towards non-capitalist social formations or sectors, instead highlighting its continuance within capitalism. Also, Harvey’s insight that this took on new forms after the 1970s usefully paved the way for a range of scholars’ analyses of superfluity, assetization, and extractivism in the digital economy. I am thinking here of Shoshana Zuboff’s critique of the “dispossession cycle” that sees Google et al. enrol millions in the creation of a “behavioral surplus” that they monetize. Kate Crawford’s mapping of AI’s dependence on extraction comes to mind. And Katharina Pistor’s studies of the legal coding of capital and its rendering in data also till ground that Harvey’s analysis of “accumulation by dispossession” helped to seed. What are some of the key insights that come to mind for you amid talk of digital dispossession?

NBT: Scholars are currently writing richly on digital feudalism, digital rentiership, and new digital financial relations under platform capitalism. Contemporary scholarship on data dispossession from critical data studies, STS, media studies and related bodies of work reveals a crucial theoretical tension in how we conceptualize the relationship between governance, extraction and epistemology. Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias mobilize the concept of “data relations” to describe the new types of human relations that emerge with data’s empire which enable the extraction of data for commodification configuring social life all over the globe into a resource for capitalist extraction. Karen Gregory and Jathan Sadowski show how platform-based dispossession works not just through data extraction, but through a deeper biopolitical process that transforms workers into "drones" who must constantly prove their worth through data metrics while losing control over their bodies, time, and labor autonomy. Moreover, as Amir Anwar, Elly Otieno and Malte Stein, points out, digital dispossession in the gig economy manifests further through a toxic combination of high operational costs and technological dependencies. In a different register, Catriona Gray argues for the need to understand data dispossession beyond extraction frameworks, and thus not simply as an analogue to land-based forms of accumulation, but as a distinct biopolitical apparatus that operates through the interaction between orders of knowledge and value. This epistemological dimension suggests, as Densua Mumford's constructive critique of existing data colonialism frameworks shows, that data dispossession works not only through overt extraction but through the legitimization of particular knowledge systems that claim universality while dismissing alternative ways of knowing. The colonial matrix of power thus operates in data economies not just through material appropriation but also through epistemological dynamics. Le Guin's provocative claim that 'nothing is yours. It is to use. It is to share. If you will not share it, you cannot use it' takes on new meaning in this context, as data economies simultaneously demand sharing while foreclosing genuine epistemological and material equitable relations.

With these critiques in mind, how might we think about the current emergence of an economic system where control and value extraction happen not only beyond, but also sometimes without direct possession? And how might we think about dispossession as also an epistemic regime which dismisses other ways of being and relating than the modern liberal subject?

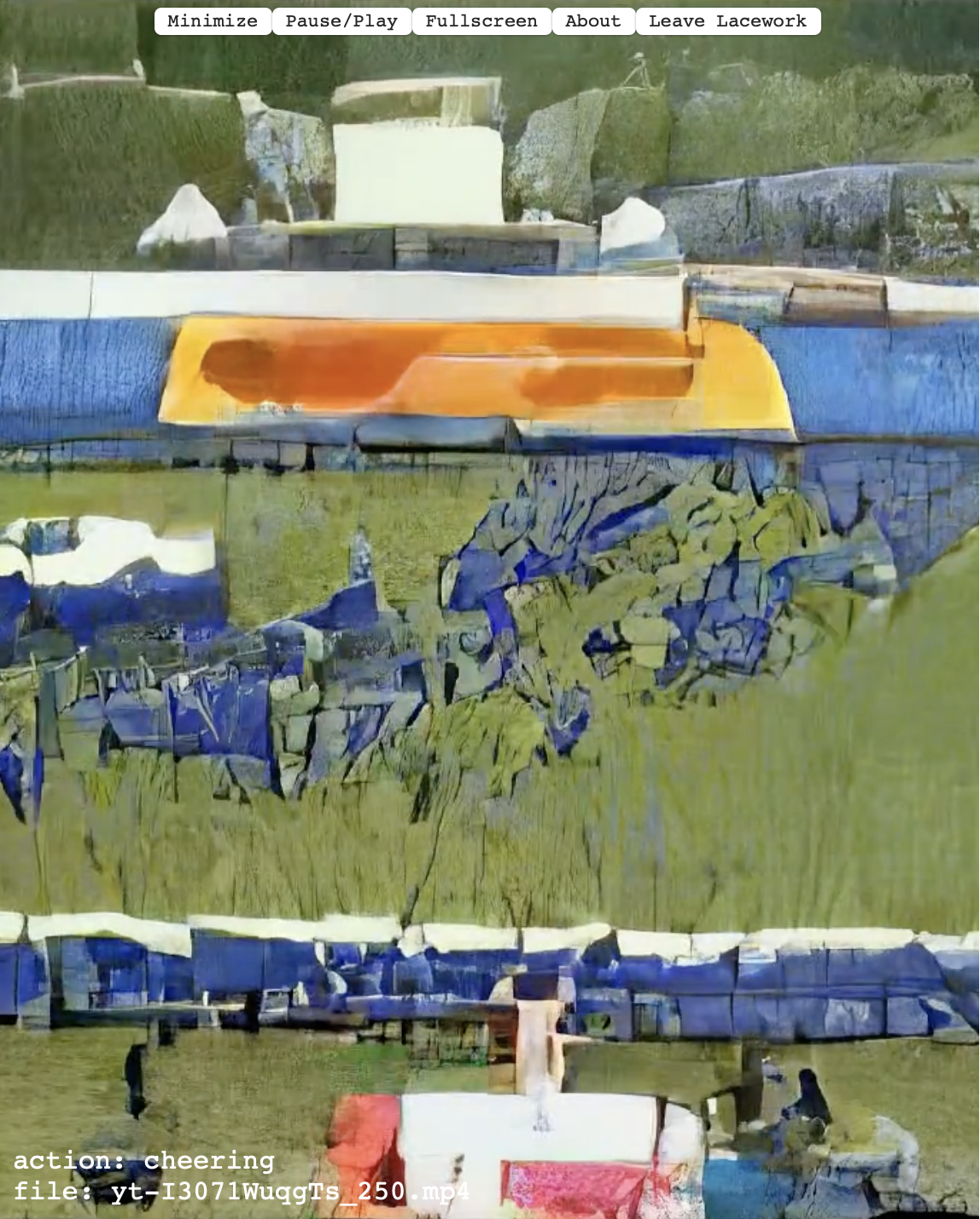

FJ: Yes, these seem like crucial questions. When I consider where literatures on dispossession seem to run their course, or what phenomena they leave under-analysed, I think of three main points. First, dispossession implies scarcity and zero-sum relations. However, value creation in the digital economy is often non-rivalrous (except in the case of raw materials used in hardware or in the allocation of limited undersea cable bandwidth). For example, when users of StackOverflow, a popular question-and-answer website for software developers, were angered by an arrangement to allow use of their words to train OpenAI's models, they were not lamenting loss of “possession”. The repurposing of postings, pursuant to contractual rights embedded in StackOverflow’s terms and conditions, allowed OpenAI to derive value from users’ collective work product without any of that value passing to them. Users experienced this as unjust, but it did not require any loss or withdrawal of user rights. Only when some users vowed to delete or deface postings to diminish their value to ChatGPT did StackOverflow threaten a “taking” in the form of retaliatory suspension of user accounts. The latter (that is, suspension of service) is a mode of exclusion that articulates quite well with the idiom of dispossession. However, the former (repurposing of terms of service to enable value-generation privileging already-powerful actors) reinforces inequality (through OpenAI’s hoarding of data and access rights with Microsoft’s backing) but not necessarily at the expense of users’ rights or access. Such arrangements leverage and intensify broader socio-economic transformations associated with the spread of derivative logic (whereby value is derived from assets without need of those assets’ ownership or possession) and the dematerialization of property through financialization.

Stack Overflow response to users purging their posts [Image credit: Mayank Parmar at Bleeping Computer]

Second, dispossession discourse subordinates exploitation to the loss or lack of property, whereas disadvantage and dependency in digital settings are often not explicable in such terms. Exploitative relations in such contexts are maintained as much by adhesion contracts and normalized practices of what Natasha Dow Schüll terms “self-fashioning” than by property rights’ allocation (although employee equity plans conferring personal property rights play a significant role). Such relations are often sustained infrastructurally too. For instance, Marc Andrejevic has written about how the management-mandated use of workplace communication platforms combines coercion with voluntarism.

Third, analyses of dispossession tend to engender a strategic focus on gaining or regaining self-possession. This narrows the range of ideas that tend to be canvassed, favouring proposals premised on non-disruption to prevailing economies alongside fantasies of individual mastery and national/regional exceptionalism. Hence, we hear that platforms’ users should be compensated for the value that “their” data help create through marginal top-up or mop-up arrangements: guaranteed basic income or digital transaction taxes. As Bao-Chau Pham and Sarah Davies have argued, initiatives like the AI Act evoke narratives of Europe’s moral superiority and value coherence that have long, bleak histories. And much regulatory attention has focused on securing individual rights to disclosure, explanation, consent, and safety that do next-to-nothing to alter those relational dynamics enabling exploitation in the first place. Salomé Viljoen is among those who have highlighted the limits of these kinds of policy initiatives. Such individualization of harms and remedies tends to pre-emptively undermine collectivizing counter-politics. Contrast, for instance, Evgeny Morozov’s efforts to rekindle a techno-utopianism centred on public institutions.

Given these problems, how else are scholars of digital media and politics talking about subjugation and privation if not in terms of dispossession? What are some approaches that you would like to see pursued further?

NBT: I am for instance deeply indebted to Louise Amoore's work on machine learning political orders, which illuminates how machine learning systems enact dispossession not merely through data extraction, but through generative mechanisms of algorithmic foreclosure (see also Katia Schwerzmann’s recent paper on the distinct political logics of enclosure and foreclosure). Her work reveals how these systems actively profit from and reinforce social fragmentation, learning from the very instabilities they produce in democratic institutions and community relations. While my own work centres the distinct materialities and ecologies of the digital, I also often find theoretical inspiration in work that helps me situate the data dispossession within broader historical and theoretical landscapes. I would like to mention three examples. Byrd, Goldstein, Melamed, and Reddy's inspiring work on "economies of dispossession" shows how contemporary financial accumulation operates through social relations configured by imperial conquest and racial capitalism. This framework reveals dispossession not simply as an act of taking, but as an ongoing relational process working through logics of abstraction, commensurability, and property-making. Butler and Athanasiou’s dialogues on dispossession further adds to this conceptual tension by highlighting dispossession's constitutive tension: it names both the material processes separating people from their means of social reproduction and the ontological condition that the sovereign self-possessed subject was always impossible. We are inherently dispossessed through relational dependencies and encounters with alterity. This double meaning illuminates how proprietary logics both enact material violence and obscure dispossession's structuring role. Moreover, as scholars like Saidiya Hartman and Marisa Fuentes demonstrate in their work on the archives of slavery, theorizing dispossession raises profound methodological challenges: how do we represent and analyze that which has been systematically erased or rendered illegible by dominant epistemological frameworks? Their careful attention to archival absences and silences offers crucial insights for examining contemporary forms of digital dispossession, where power often works through processes of erasure and illegibility.

Lacework, Action: Mowing. Attribution to the original source has been broken here by the dataset construction process of Moments in Time, but file name pennsylvania-united-states-video-idmr_00009847_2.mp4 (at the bottom of the video) gestures at where it was initially scraped from. [Image credit: Everest Pipkin's Lacework ]

The challenge for scholars working on dispossession in the digital realm thus becomes theorizing grounded relationality that acknowledges and gives an account of constitutive dispossession while resisting its weaponization through property regimes. This resonates with Le Guin's reflections on sharing – not as a celebration of platform capitalism's extractive sharing economy, but as a radical recognition of our inherent interdependence and the possibility of different forms of collective use.

Which brings me to the following set of questions: Legal mechanisms can both protect and foreclose democratic rights. As Amoore argues, this tension becomes even more acute in our algorithmic age, where automated systems actively learn from and exploit legal frameworks meant to safeguard citizens and communities. This raises a crucial question: how might we engage with legal mechanisms and rights-based frameworks while remaining attentive to law's role in structuring the very conditions of dispossession we seek to challenge? How might we theorize legal strategies that can work both within and against existing juridical orders to advance alternative forms of relationality and collective claims?

FJ: Legal strategies do allow for experimentation with new ways of understanding use, collectivizing digital infrastructure, countering platforms’ anti-union conduct, and conceiving of what it is to share. There are a range of techniques commonly used in corporate law to defend against unwanted loss of control (so-called poison pills, for example, that defend against hostile takeover); it would be interesting to explore whether they could be reworked to defend against concentrations of power averse to workers’ interests. This takes me back to the Le Guin epigraph. Her call for non-proprietary sharing evokes mutual aid ideas. Yet even when written, per her subtitle, these were “ambiguous[ly] utopia[n]” ideas. In the decades since, the demand to share has taken on a dystopian tenor, implying relentless exposure and incessant searching via technological infrastructure designed in large part to enrich the few and empower the extremes. The task now seems to be to rekindle “ambiguous[ly] utopia[n]” prospects amid these phenomena.

This conversation reveals how traditional frameworks of dispossession, while valuable, may not fully capture the complexities of exploitation in today's digital economy. Fleur and Nanna discuss how digital dispossession operates beyond simple notions of loss or deprivation of property—it functions through complex infrastructures of control, data relations, and epistemological and ontological frameworks that don't necessarily require direct possession to extract value. Le Guin's utopian vision that "nothing is yours... it is to share" has been twisted in our digital age, where "sharing" often facilitates new forms of exploitation and value extraction. The dialogue points toward the need for new theoretical and legal approaches that can address these emerging forms of power, while remaining attentive to both the material and relational dimensions of digital exploitation and interdependence. As we navigate these challenges, the task ahead lies not just in critiquing current systems, but in reclaiming Le Guin's radical vision of sharing by imagining and building alternative frameworks for digital relations that could foster more equitable and collective forms of control and co-existence.

Published: 12/09/2024