Caring about Psychedelic Science: An Alternative Approach to Studying Hype

Kai River Blevins

03/01/2025 | Reflections

Screenshot of an article about psychedelic hype [Image credit: Love 2019]

But hype is a “particular kind of exaggeration,” as the philosopher Kristen Intemann argues. Intemann’s work on hype focuses on how it is a “value-laden concept,” one that makes a judgment about two things: “(1) judgments about the proper goals of science communication in specific contexts, and (2) judgments about what constitutes an ‘exaggeration’ in that context” (280). In other words, recognizing or labeling a stretch of discourse as “hype” is an evaluation of how a scientific claim is used within a particular context; focusing on why it was being used and whether the evidence for the claim was appropriately communicated.

In recent years, there has been a growing literature within academia and journalism looking critically at the relationship between hype and psychedelic science. Bill of Health, the online publication of Harvard’s Petrie-Flom Center, even had a special issue titled “Critical Psychedelic Studies: Correcting the Hype” last year. Neşe Devenot, in the introduction to that special issue, writes that “a wave of scholarship and commentaries has emphasized the ethical importance of nuanced science communication about the still-nascent field of psychedelic medicine.” This ethical dimension arises from the ways that hype can cause harm (Harrison et al., 2025) or be exploited by venture capitalists (Tvorun-Dunn 2024). Within psychedelic discourse, identifying hype is a critical practice that attempts to prevent (further) harm and stop economic exploitation, among other goals. While this is a crucial practice that I support, it continues a tradition of conceptualizing hype in representational terms.

The Representational Approach

I have no problems with what I call the representational approach to hype, an approach that takes hype to be a matter of how people communicate about science within specific contexts. It is a useful way to identify how scientific evidence can be stretched within communicative interactions. This allows us to track trends in how people communicate about an often-emerging object of scientific knowledge production, to examine how unique claims circulate, and to understand the various effects these claims have. In short, the representational approach is a valuable diagnostic tool and an explanatory framework.

These strengths also limit the representational approach. Since hype is a matter of communication about objects of scientific knowledge production, we tend to get stuck evaluating only those interactions where such communication is present. This means that we address hype by addressing science communication. For example, in an article on hype in stem cell research, Caulfield and colleagues (2016) examine guidelines developed by the International Society for Stem Cell Research that might help to reduce hype. These guidelines include, for the first time, the obligation of researchers to ensure that their research is accurately represented. Yaden and colleagues (2022) take a similar perspective, with their only recommendation for countering hype being that researchers and clinicians “have an ethical mandate to dispute claims not supported by available evidence” (944). In these cases, since hype is a problem of representation, the way to address it is through changing how we represent scientific knowledge.

The ethical and political project of making sure scientific knowledge is communicated accurately is important, but it leaves me wondering: Why do people make hype statements in the first place? The representational approach takes this question to be about the issue of communication, of knowledge transmission. Either people unintentionally misrepresent scientific knowledge—perhaps because they have only partially represented information or because they are not skilled in scientific discourse—or they intentionally misrepresent scientific knowledge—perhaps because they have something to gain or are committed to causing harm.

In my ethnographic and archival research on psychedelics in the United States (Blevins and Small 2024, Blevins 2025), I have not only identified instances of hype, but I have explored why people exaggerate scientific knowledge about psychedelics. The representational approach has been a useful tool for me. I have seen how scientific knowledge is misrepresented and how people make evaluations about communication to suggest—or explicitly claim—that someone has made a statement that qualifies as hype.

Yet, I have been unsatisfied with the representational approach. It narrows our gaze to moments of communication, starting with an evaluation of what an individual is saying before we can start to understand the richness of that person’s life. In this way, the representational approach has made me uneasy. It makes me feel immediately suspicious of others, interpreting everything about their life through the lens of an evaluation about something they said at one particular moment in time. As important as this approach is, I have wondered about an alternative way to study hype. What might that look like?

Hype as a Matter of Care

I have learned through my research that people not only communicate often about psychedelic science, but that they have “a strong sense of attachment and commitment” to it (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 42). In other words, people care about psychedelic science. This fact is often lost or subordinated in the representational approach; what matters is whether a statement is an exaggeration, not how an individual feels about the information they are communicating about. When we take hype as a matter of care, we not only begin to see the importance of communicating about science for a certain person or public, but we also begin to see the role that the object of scientific knowledge plays in an individual’s or a public’s world (Brown 2003).

The difference between the representational approach and the care approach starts with how the term “context” is defined. On the representational approach, context is about the immediate setting in which a statement is uttered. But for the care approach, context is vastly expanded. Knowledge is situated (Haraway 1988), meaning that “knowing and thinking are inconceivable without a multitude of relations that also make possible the worlds we think with” (Puig de la Bellacasa 2012, 198). The context for a statement, then, includes this “multitude of relations,” not as static background conditions, but as dynamic relations between an individual and their world. In short, the care approach explicitly attends to how an individual actively relates to their world in order to understand why people make exaggerated statements about scientific knowledge.

Studying how someone “actively relates” to their world can be quite unwieldy, though. What would that include? Rather, what wouldn’t that include? María Puig de la Bellacasa’s work is helpful here. In her review of influential feminist theories of care, she draws out three dimensions that make up the concept: “care as maintenance doings and work, affective engagement, and ethico-political involvement” (2017, 6). These three dimensions allow us to study how hype is situated without getting lost in labelling every act as an instance of care.

Care Work

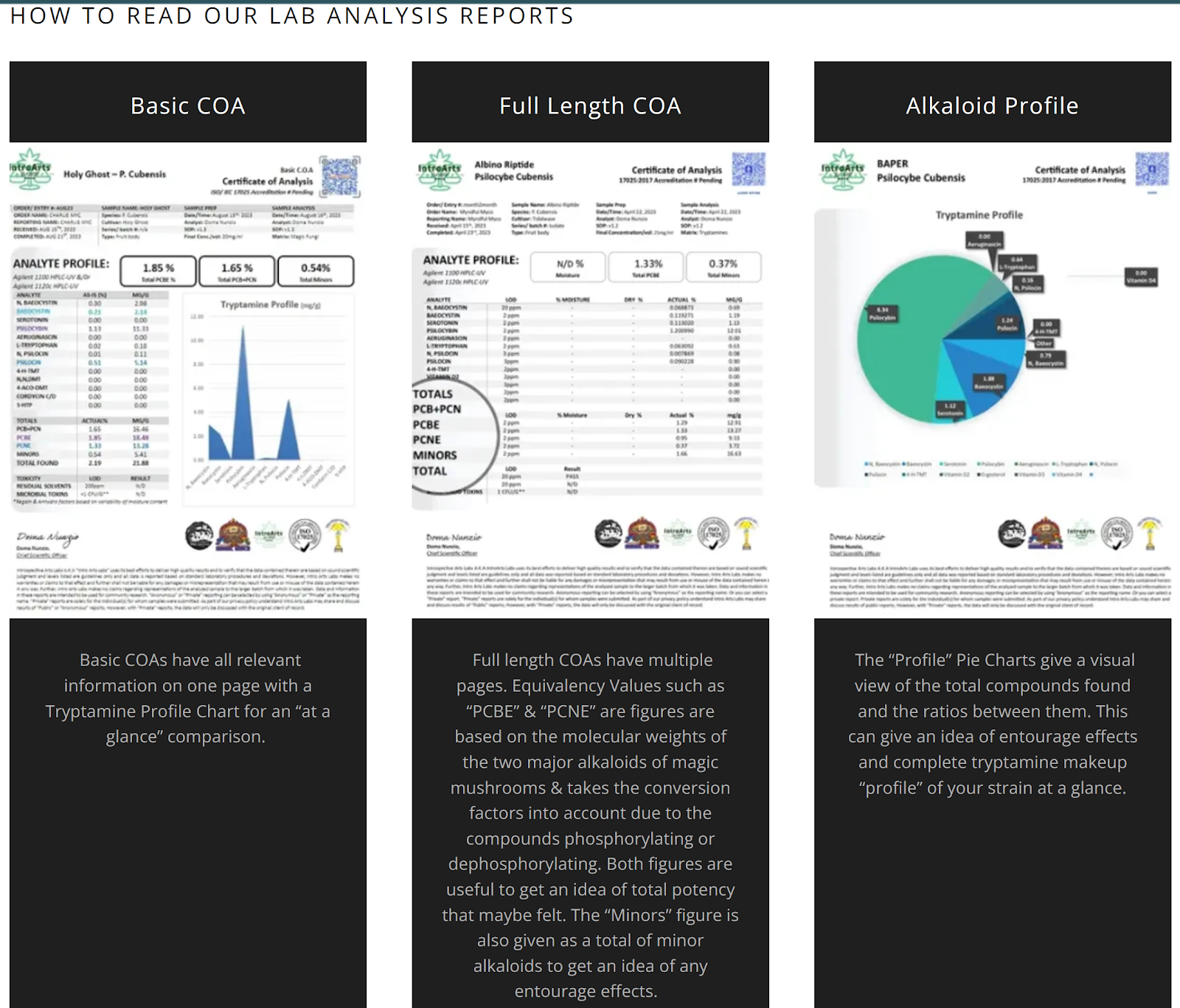

In my fieldwork, I have seen many ways that people do maintenance work for psychedelic science. One example is from one of my interlocutors, Jimmy, who runs an underground psilocybin testing lab in the Mid-Atlantic region. Jimmy cares about psychedelic science by literally doing it. He is part of a network of underground labs on the East Coast of the United States that are working together to create an open-source standard for high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) testing of psilocybin mushrooms, a method that’s controversial in the wider mycology community but that he and his colleagues believe yield the highest accuracy in terms of identifying the compounds present in a given strain. Jimmy believes that identifying the compounds will help to show how mushrooms are actually effective, something another mycologist I worked with described as a holistic approach that does not extract psilocybin from the other alkaloids present in whole mushrooms.

Another way Jimmy cares about science is by circulating it. On his website, Jimmy posts readouts from his HPLC tests on various strains. He also has explanations of these readouts, showing people how to read them and why the information they provide is relevant. But I want to draw attention to one document that Jimmy excitedly shared with me, which is his guide to antidepressants. In this document and in others, Jimmy does maintenance work on psychedelic science through citation, summarization, and application. He shows that he cares about psychedelic science by extending its circulation beyond traditional venues of scientific knowledge production.

In this example, doing science and circulating science are matters of care. Whether or not Jimmy’s lab results or his guide to antidepressants count as instances of hype is not my point. The lesson I want to draw from care work is that it helps us begin to see the broader commitments and patterns of activity in which communicative acts that reference psychedelic science are situated. These commitments and patterns of activity, I argue, must be part of any evaluation about whether a given statement counts as hype. In other words, no statement comes without its world. The care approach insists that in attempts to prevent hype from occurring, we must address the material practices through which statements get articulated.

Affective Engagement

Screenshot of Right to Try demonstration at DEA headquarters in Arlington, VA, USA [Image credit: Reconsider Media 2022]

At the press conference before the demonstration, multiple individuals spoke about the scientific evidence that made psilocybin a candidate for the legal exemption Erinn was seeking. Kim, Erinn’s nurse, spoke forcefully about studies where psilocybin was used to treat end of life anxiety: “What we know from those studies is that psilocybin gives people their life back in a way that allows them to enjoy what time they have left, rather than to be wrestling with the incredible amount of fear and anxiety.”

My research has shown me that caring for psychedelic science is inherently affective. What I want to highlight is that affective engagement reveals the complexity and existential significance of the situations in which communicative acts are uttered. The care approach requires that we examine what it is about a specific domain of scientific knowledge that moves people. As Kim has described elsewhere, being a hospice nurse shapes her affective attachment to psychedelic science, and the work of maintaining that attachment entails an affective deepening.

Ethico-Political Involvement

This brings me to the third aspect of care identified by Puig de la Bellacasa—“ethico-political involvement”—which is most pronounced in political advocacy. This past year, psychedelic publics were focused on whether the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would approve an application for MDMA-assisted therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). After an advisory committee recommended against approval in June 2024 based on their critiques of the research design, veteran advocates and elected officials began publicly pressuring the FDA to approve the application.

This ad hoc coalition was led by Heroic Hearts Project, a nonprofit organization connecting U.S. military veterans to psychedelic therapy retreats outside the country. They responded to the FDA Advisory Committee’s recommendation by writing an open letter that detailed the ethical imperative to approve it “because of the overwhelming scientific evidence in favor of [its] efficacy.” They went on to say that “Too many lives are at stake for anything other than science to guide the FDA’s decision. Veterans’ lives are now dependent on the FDA’s ability to separate fact from opinion.”

For the Heroic Hearts Project, scientific knowledge is the discursive object that mediates care practices. Their involvement in the ethics of a political process designed to evaluate scientific evidence led them to not only mobilize a coalition in support of a certain outcome, but also to denounce people who were raising critical questions about that evidence. Their care for psychedelic science included sharing a call by a member of congress to doxx critical psychedelic studies researchers and former patients harmed in MDMA clinical trials. In addition to the open letter, HHP has also practiced care through holding a press conference in front of the US Capitol with members of congress in which they argue for the irrefutability of psychedelic science and the urgent need to ground political decisions on its results.

Screenshot of Heroic Hearts Project press conference in front of U.S. Capitol Building [Image credit: Heroic Hearts Project 2024]

Attending to ethico-political forms of care reveals the wider context in which the mobilization of psychedelic science occurs, as well as the norms and values that mediate orientations to scientific evidence more broadly. As Puig de la Bellacasa argues, “care obliges us to constant fostering, not only because it is in its very nature to be about mundane maintenance and repair, but because a world’s degree of liveability might well depend on the caring accomplished within it” (2012, 198). Thinking about hype as a matter of care lets us focus not only on the truth value of the communicative act but on its ethico-political significance.

The Care Approach to Hype

So how does care help us understand hype? And where does this approach focus our attention in responding to the problems that result from hype? My argument is that we need a critical phenomenology of care to answer these questions. Since hype emerges from care, we need to understand the experience of caring for psychedelic science in each of these three dimensions. More than that, our interventions into hype need to be at the level of care. Let me offer some preliminary ideas for what I mean by that.

In the first dimension of maintenance work, we might examine the conditions of possibility for Jimmy’s engagement in psychedelic science. For example, in a discussion about his decision to enter the gray market as a vendor, Jimmy described how he was playing “the long game.” No one else in the local market tests psilocybin using his method or provides proof of a test to customers. Cast in terms of a market advantage, Jimmy is sure that there will be a legal, adult-use market in the next five to seven years, and he will have a solid customer base through providing a form of consumer protection no one else can replicate. The economic reasoning guiding Jimmy’s care for psychedelic science cannot be separated from an evaluation of his claim about the healing potential of psilocybin mushrooms.

In the second dimension of affective engagement, we might examine the conditions of possibility of turning to psychedelic science as medical science. Here I want to use the case of the Heroic Hearts Project. The reason for their affective attachment to psychedelic science is its healing potential, but that healing potential is actualized in the midst of a veteran suicide epidemic, significant problems with the veteran health care system, and longstanding problems of reintegration into civilian society. Moreover, there is a widespread, positive affective attachment to the military in American public life, one that was harnessed and amplified by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies in its strategy of making veterans the paradigmatic recipient population of MDMA-AT. These affective attachments and the ways Heroic Hearts Project cares for psychedelic science cannot be ignored when we evaluate their claims.

In the third dimension—ethico-political involvement—we might examine the conditions of possibility for the Right to Try campaign itself. How was it that a group could make claims on the state about its regulation of a doctor’s care for their patient? Conceptions of scientific authority, state authority, and the proper relation between the two was central, but so too was the history of patient advocacy and liberalism. By confronting the state, organizing to raise awareness in Congress, engaging with the press, and more, the RTT campaign mobilized existing practices and norms of American political participation that gave its claims a moral authority external to psychedelic science itself. We cannot evaluate claims about psychedelic science independently of dominant modes for ethical and political expression.

These examples demonstrate what is required when applying a care approach. In terms of care work, participation in a scientific discourse is treated both in sociohistorical terms and in terms of the material practices that give meaning to that discourse for an individual. In terms of affective engagement, the meaning of a statement is evaluated not only by referencing communicative norms within a given context, but by examining the existential significance of mobilizing a scientific discourse. Finally, in terms of ethico-political involvement, locally salient modes of ethical and political action structure how people relate to a given scientific discourse. Each of these applications suggest that our interventions cannot merely address accuracy in communication. Rather, we must transform how we care about a given scientific discourse to prevent hype statements from occurring and having the effects they do. This is, admittedly, a much more difficult task than simply stating that we must stop the exaggeration of scientific knowledge.

Yet, the care approach and the representational approach are not at odds; they are complementary. If we want to address hype and the problems it poses, we need the tools that both approaches offer. The representational approach is better at identifying when hype has happened, helping us to attend to truth claims and their various effects. On the other hand, the care approach is better at understanding why hype has happened, helping us attend to the meaning of a scientific discourse in the lives of people who make truth claims. In attending to that meaning more closely, my hope is that future studies of hype will not lose sight of the existential significance of psychedelic science; not for exceptionalist reasons (Cheung et al. 2025), but because it offers a window into the structures of contemporary life and the possibilities for transforming the world for everyone, regardless of whether they use psychedelics.

Kai River Blevins (they/them) is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Anthropology at George Washington University. Their dissertation project is an ethnographic and archival exploration of the ideological work involved in participating in emergent psychedelic publics in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Focusing on the ethical dimensions of participation, they are interested in the social and political effects that psychedelic publics are having on American society through shaping discourses of health, freedom, and consumption. Kai’s research draws on linguistic anthropology, critical phenomenology, political theory, and feminist science and technology studies.

Published: 03/01/2025