The Heartware approach: how cultural values drive sustainable socio-technical change

Author: Zeeda Fatimah Mohamad, Department of Science and Technology Studies, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

Editor: Auriane van der Vaeren, 4S Backchannels

04/07/2025 | Reflections

Introduction

The sociology of science has long explored the relationship between knowledge production and society, particularly regarding expertise, public participation, and the democratization of knowledge (Jasanoff, 2004; Latour & Woolgar, 1986). Traditional approaches to environmental governance often prioritize technological solutions (“Hardware”) and institutional mechanisms (“Software”). However, these approaches frequently overlook the significance of shared values, cultural narratives, and lived experiences—elements central to what we call the “Heartware”.

This essay discusses the Heartware approach to sustainability science as explored by my team’s research on the Heartware-Hardware-Software governance framework and Place-Based Citizen Science (PBCS) in watershed management. By situating these concepts within broader discussions in the sociology of science, this work highlights the role of situated knowledge, participatory epistemology, and socio-technical systems in advancing sustainability transitions.

Citizen science for water conservation in Malaysia (Mohamad et al., 2021)

The Heartware approach

The Heartware approach emerged from a growing recognition that technical and institutional interventions alone are insufficient for effective environmental governance. Inspired by Japan’s Lake Biwa environmental movement, Heartware in our work emphasizes the critical role of the subjective, humanistic dimensions of sustainability—emphasizing cultural traditions, social values, and emotional connections to the environment (Mohamad et al., 2015, 2018).

Heartware aligns with Donna Haraway’s (Haraway, 1988) notion of situated knowledge, which posits that all knowledge is produced within specific social, historical, and cultural contexts. By emphasizing shared values and place-based meanings, the Heartware approach challenges the assumption that environmental management can be solely dictated by universal scientific models. Instead, it acknowledges that sustainability efforts must be deeply embedded in localized histories, spiritual beliefs, and social relationships. Our comparative research on watershed conservation in Japan and Malaysia highlights how different communities attach varying degrees of significance to lakes and rivers based on religious traditions, livelihood dependencies, and historical narratives—factors often overlooked in conventional environmental governance (Mohamad et al., 2015, 2018).

Training citizen scientists for data collection for water conservation in Malaysia (Mohamad et al., 2021)

Rethinking sustainability governance through Heartware

Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholars have long recognized that technological systems are not neutral tools but are embedded within social relations, institutional structures, and cultural values (Bijker et al., 1987). The Heartware approach contributes to this discourse by conceptualizing sustainability governance as a Heartware-Hardware-Software system, where scientific and technological (Hardware), institutional (Software), and humanistic (Heartware) dimensions must be dynamically integrated (Mohamad et al., 2015, 2018).

This perspective builds upon Bruno Latour’s (Latour, 1993) actor-network theory, which emphasizes the co-construction of social and technical elements in shaping scientific outcomes. In Heartware-driven watershed management, lakes and rivers are not merely hydrological and hydrodynamic entities but are also constituted through a network of human relationships, policy discourses, institutional reforms, and how it relates to culturally relevant symbolic meanings (Abd. Kadir, MacBride-Stewart & Mohamad, 2024). By treating environmental governance as an emergent socio-technical system, the Heartware approach provides a more nuanced framework for understanding sustainability transitions within specific cultural contexts.

Our comparative case studies in Japan and Malaysia demonstrate that long-term watershed conservation efforts are most effective when Hardware (policy and technology) and Software (institutions and governance) interventions are built upon a strong Heartware foundation (Mohamad et al., 2015, 2018). This foundation includes:

- Community-shared values that inspire collective voluntary action.

- The multifaceted role of volunteers, who operate at different levels of power to galvanize self-directed initiatives.

- Heartware-driven adaptive governance, where watershed communities can self-manage conflicts that might otherwise obstruct long-term action.

In the context of watershed conservation, the community-shared values extend beyond utilitarian concerns to include historical, cultural, and symbolic meanings, further reinforcing the role of Heartware in sustainability governance.

Place-Based Citizen Science as a tool for Heartware

Building on a Heartware-driven sustainability governance, we have also explored the potential of Place-Based Citizen Science (PBCS) as a practical tool for integrating Heartware into watershed management. Unlike conventional citizen science, which often relies on large-scale crowdsourcing, PBCS prioritizes local engagement and site-specific knowledge. This approach allows communities to generate and interpret data based on their lived experiences, fostering a deeper connection between scientific findings and environmental action (Mohamad et al., 2021; Mohamad, 2024).

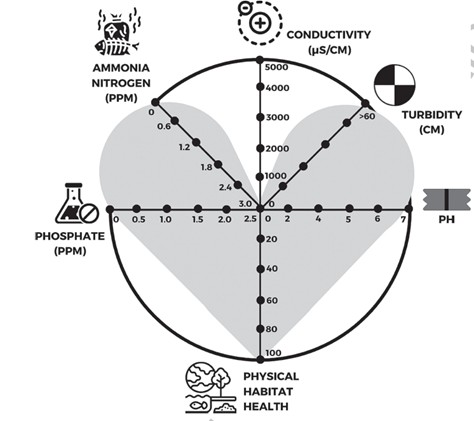

A key example is the Eco-Heart Index (see below diagram): it is a PBCS tool designed to enable communities to visually interpret water quality using culturally resonant symbols (Sakai et al., 2018). Unlike conventional water quality indices that only rely on numerical scores, the Eco-Heart Index represents pollution levels through a heart-shaped visualization, making the data more intuitive and emotionally compelling for non-experts (Sakai et al., 2018). In the local Bahasa Malaysia language, the heart as a symbol and word evokes strong emotional reflections through phrases such as:

- Patah hati (broken heartedness)

- Menjentik hati (re-enchanting the heart)

- Hati penuh (full heartedness, symbolizing holistic well-being)

Eco-heart water quality index (Mohamad et al., 2021)

The Eco-Heart Index determines water quality by shaping the heart symbol—a full heart represents clean water, while a broken or distorted heart signifies pollution (Sakai et al., 2018). This visual storytelling approach makes water quality results accessible across economic, cultural, and religious backgrounds, improving public communication of scientific findings (Newell, 2012). Furthermore, this affective symbolism can be further enhanced through locally relevant religious and spiritual narratives, as water plays a central role in purification rituals for the local Muslim and Hindu communities. Caring for rivers can thus be framed as an act of devotion, reinforcing conservation efforts through cultural and spiritual significance.

Eco-Heart Index: pre-testing protocols with the community (Mohamad et al., 2021)

This participatory epistemology aligns with STS discussions on lay expertise, which recognize that non-scientists possess valuable knowledge that can enhance scientific inquiry (Wynne, 1992). The Eco-Heart Index demonstrates that scientific literacy is not just about translating technical information, but about reconfiguring how knowledge is communicated and acted upon. By involving local participants in data collection, interpretation, and advocacy, PBCS fosters a relational knowledge system, where scientific and local epistemologies co-evolve (Callon et al., 2009).

Conclusion: the Heartware approach as a theoretical contribution to STS

The sociology of science has consistently emphasized the need to democratize knowledge production and challenge the hegemony of expert-driven governance models. The Heartware approach contributes to this dialogue by offering a relational, participatory, and culturally embedded framework for sustainability science. By foregrounding shared values, community narratives, and affective engagement, it extends STS discussions on situated knowledge, participatory epistemology, and socio-technical systems.

As global environmental challenges intensify, there is an urgent need for governance models that are not only scientifically rigorous but also socially meaningful and politically sustainable. The Heartware approach provides an example of how interdisciplinary research can bridge the gap between technical expertise and local agency, fostering a more holistic and inclusive paradigm for environmental stewardship. By embedding sustainability governance within the cultural and historical fabric of communities, it offers a promising pathway for enhancing the relationship between science, society, and the environment in the Anthropocene.

Zeeda Fatimah Mohamad is a researcher in Sustainability Science at the Universiti Malaya, Malaysia, who is passionate about the potential of action-oriented research in dealing with the challenges of sustainability transitions in latecomer countries. She is currently an Associate Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, Faculty of Science, and the Director of the Universiti Malaya Sustainable Development Centre.

Published: 04/07/2025