Locating STS in Southeast Asia: a Belgian migrant looking for a place of belonging

Author and editor: Auriane van der Vaeren, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand05.05.2025 | Reflections

Cabin crew, please prepare for landing. In the summer of 2022, after finishing my Science & Technology Studies (STS) master’s courses at the University of Vienna, I reunited with my partner in Bangkok. Vienna’s STS programme had so monstrously stimulated my appetite for STS, that I was determined to find an STS point of anchorage in my new environment. And that is what this contribution is about: about sharing my experience of locating STS hubs in Thailand and Southeast Asia (SEA) as a foreigner.

Taking a direction in an unfamiliar space

All I knew upon arriving in Bangkok was my European partner who had moved here for work. And all I had seen of Asia were touristic highlights of Myanmar 7 years earlier. Everything about this society’s matrix—its social etiquette and the way Thai social life is structured and organised—was new to me: why one is greeted with hands folded in front of the chest or mouth; why passengers in packed public transports delicately and silently worm their way through to the exit without ever vocalising an “excuse me”; why it is not customary to hold doors for those walking behind; or why some lower the head apologetically upon crossing one’s path.

I knew that I came with baggage in a place that itself has baggage. But all these everyday routine and banal customs for Thai individuals were intriguing to me. Through daily encounters between my mode of socially functioning and the Thai way of social life, I was able to realise the tenacity of my social matrix: able to realise that rational awareness alone does not suffice for the more profound situation of my mode of being in this world, and that embodied awareness is at least as relevant to emancipate myself from my original social matrix1, 2.

Disorientation

In those early days, I believed (or wanted to believe) that my disorientation would be limited to the physical world: having no idea where to look for STS in the real world—which roads to walk, which buildings to enter, which doors to open, which humans to interact with—I imagined (or hoped) that finding out about an STS hub in Thailand was just a click away, much like the STS communities I knew of in Europe, such as STS Austria and EASST, were available as digital low-hanging fruit.

As a millennial baby that grew up with Web 1.0, I was highly confident in my online surfing skills. Since primary school, I had been perfecting the flexing of my body into a static office position and the curving of my fingers on a keyboard to prompt digital queries—a navigation technique that so far had only been validated. With Thailand being a fellow network society, I thus expected to encounter no significant barrier other than language upon navigating the online world.

Alas, my DuckDuckGo and Google Search browser results did not prove very successful: I easily found the STS hub in Singapore, but for a region that counts 11 countries, I could not imagine that there was zero STS activity elsewhere. Tempting my luck with English-language STS journals, papers that discussed the state of STS in SEA mostly dwelled on Singapore, and publications with country-specific discussions that I looked at were generally authored by either indigenous scholars affiliated with universities in East Asia, Singapore, the UK, and the USA, or international scholars affiliated with universities in Australia, Singapore, and the USA. But the fact that 4S Backchannels was then interested in my editorial assistance to help visibilise the STS community of SEA surely had to mean that there was more to this region than was meeting my Web browsers’ eyes.

Only after a lengthier process—contacting various authors and scanning through university staff and department pages—did the search engine fairy decide to wave its magic wand and let some bits of information pass the floodgates of mysterious ranking factors. In fact, after connecting with fellow STS scholars in the region, I understood that my hassle was not an isolated one3.

But things are changing.

Chulalongkorn University Central Library

In terms of regional coordination, Fung (Kenneth) Hon Ngen, from the STS department at Universiti Malaya, Malaysia, set up a regional STS network in November 2024, which currently exists as a WhatsApp group. In terms of the regional scholarship’s online visibility, Tobias Burgers and Ian Scott Kalman from Fulbright University, Vietnam, are currently editing a conference proceedings about STS in SEA for East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal, and Kenneth too is looking into the creation of a—possibly multilingual—special issue on this topic.

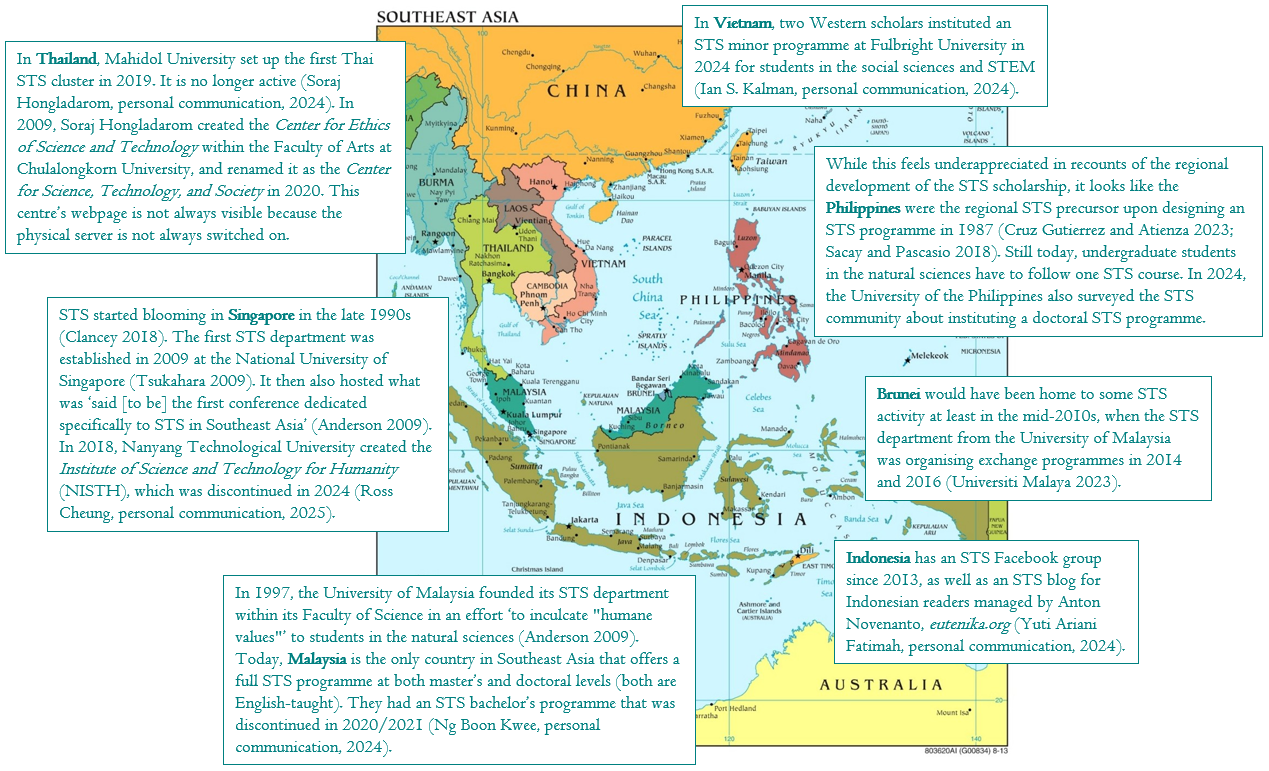

The effects of these initiatives remain to be determined, but surely they support the further regional affirmation of the STS scholarship and the further ‘decentering’ of STS (Bruun Jensen 2021). To contribute to these efforts to visibilise what is a buzzing STS community, here below, I share a ‘patchy and partial’ overview of what I was able to assemble in terms of STS hubs in SEA (Anderson 2009). Clearly, the regional STS community is much larger and more vibrant than what a first look into the crowded English-speaking online world would reverberate upon first prompt.

STS in SEA [background map by Vidiani.com]. Links to country hubs: Indonesia Facebook, Indonesia eutenika.org, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Mahidol University, Vietnam. Embedded references: Anderson 2009; Clancey 2018; Cruz Gutierrez and Atienza 2023; Sacay and Pascasio 2018; Tsukahara 2009; Universiti Malaya 2023.

My move to Bangkok flagrantly illustrates the extent to which I have been performed by the network society4: when my navigation system went blank in a physical reality that was of an entirely different social design than the one I knew, I intuitively turned toward the digital world.

A network society survives on the premise that the digital world provides accurate representations of the material one. Through pledging allegiance to the digital world, such society relegates matter to a secondary position, and tends to reify the idea that accurate knowledge about the world can be produced without experiencing it physically. Whereas, what my quest for locating STS in Thailand and SEA exposed so clearly, is that the body is at least as relevant as the mind for producing—and incorporating—objective knowledge.

Not only has this brought me to ponder more closely how it is that my mind became so much more trustworthy than my body for producing knowledge about real-world phenomena. It also brought me to wonder—like Karen Barad asking ‘[h]ow language c[a]me to be more trustworthy than matter’ (Barad 2005)—how it is that digits have come to be so much more trustworthy than matter to mediate reality. I believe these questions are particularly relevant at times where our allegiance to the digital only seems to amplify with an ever-growing permeation of artificial intelligence and its further reification of the myth of disembodied objectivity (Haraway 1988).

Notes

1. I do not believe this means one has to travel the world or live abroad to realise that learning from books alone, that engaging the mind alone, does not suffice to situate our mode of being in the world.

2. My original social matrix was given to me in good faith, but for a world that is constantly changing, any matrix is always already obsolete. Which is why I believe social emancipation is unavoidable—whether or not we choose for it.

3. It was also when I realised that STS scholars are not always aware of the existence of an STS research centre within their university.

4. A society that has ‘shift[ed] from traditional mass media to a system of horizontal communication networks organized around the Internet and wireless communication [whereby] virtuality [has become] an essential dimension of our reality’ (Castells 2010, p. xviii).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers from the STS department of the University of Vienna for their feedback on a very early and different draft a year ago: it was at the onset of a long experimentation with the text.

Images

All images were taken in Bangkok between 2022 and 2024 by me.

Auriane van der Vaeren is a research assistant at the Center for Science, Technology, and Society at Chulalongkorn University (Thailand), and an assistant editor at 4S Backchannels for East and Southeast Asia.

Published: 05/05/2025