Exploring Lay Knowledge in a Chinese Village During the COVID-19 Period

Siyi ChenMichaela Clark edited this post.

08/18/2025 | Reflections

Lay epidemiology

The concept of lay epidemiology was proposed by medical anthropologists in the 1990s, focusing on how those without specialized expertise understand disease in everyday life. It suggests that public discourses and practices at work in times of epidemic disease are linked to certain cultural norms. “Lay” and “scientific” epidemiology represent differing ways of understanding illness and diseases. Scientific epidemiology emphasizes evidence-based reasoning grounded in data such as statistical models, whereas lay epidemiology is shaped by cultural beliefs within social contexts. In existing literature, lay epidemiology is often seen as a counterpart to scientific epidemiology. This is to say that scientific narratives often give way to local knowledge, which frequently guides ordinary health practices and can occasionally represent wisdom in response to scientific interventions.

In my work on the COVID-19 pandemic in rural China, I reveal a distinct form of lay epidemiology – one that moves beyond the view of lay and expert knowledge as opposing forces. Unlike existing research that emphasizes lay epidemiology as rooted in local culture and life experience, I further identify lay epidemiology here to have unintentionally caused suffering to individuals who recovered from COVID-19 infection. This finding complicates the prevailing sense of what lay epidemiology is by demonstrating that it can function as a potential source of stigma, especially in times of an outbreak of contagious disease.

Homemade masks were a common occurrence during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Image credit: AL-U-MA / Adobe Stock]

Research background and ethnography

At the end of 2021, the dominant COVID-19 variant shifted from Delta to Omicron, a strain with significantly higher transmissibility. However, its severity decreased, leading to a higher proportion of mild or asymptomatic cases. While most countries around the world were gradually easing strict COVID-19 measures, China officially introduced the “dynamic zero-COVID” (dongtai qingling, 动态清零) policy. This approach aimed to maintain zero fatalities by implementing stringent containment measures.

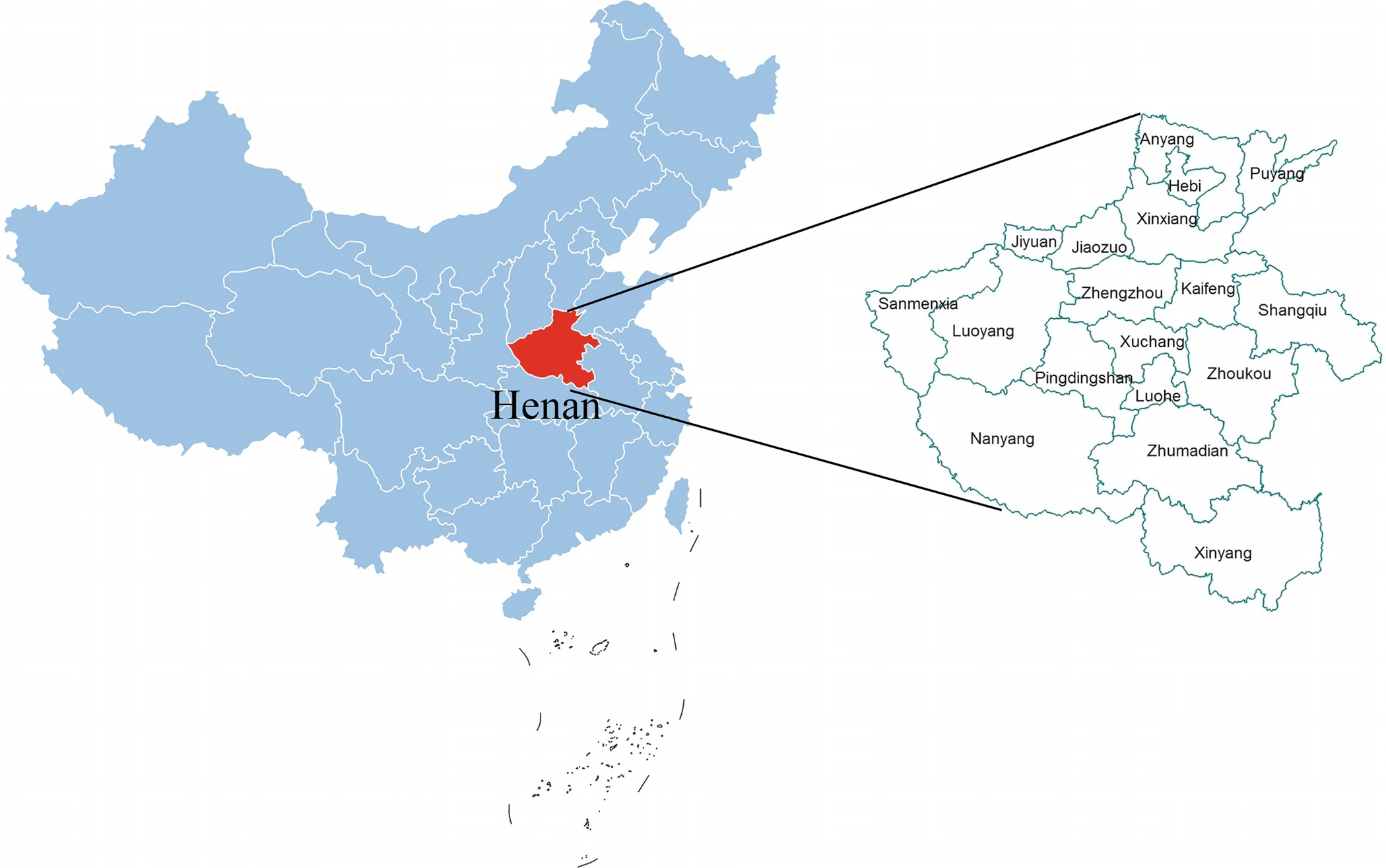

It was during this period, between December 2021 and November 2022, that I began my ethnographic research in a village of Henan province in central China. Here, I interviewed a wide range of people from both within and outside the village, including COVID-19 survivors, their family members, fellow villagers, as well as local officials and local medical staff.

Many villages in Henan were negatively affected by China's HIV crisis in the 1990s. [Image credit: Wang et al 2020]

The village in question was known as an “AIDS village”(aizi cun, 艾滋村) as it had been hit by an HIV crisis in the 1990s. This crisis was triggered by economic reforms that left previously state-funded public institutions underfunded. In response, the local government sought alternative revenue streams that saw commercial blood donation become widespread in rural central China, particularly in Henan. However, the use of unsanitized equipment during commercial blood donation led to widespread HIV infections in the village and resulted in numerous deaths. Two decades later, this same village was struck by the Delta variant of Covid-19 and several villagers were infected.

In my study, I found that villagers who had never been infected with COVID-19 continued to perceive individuals with a history of this infection as contagious, even after they had fully recovered. This distinct lay epidemiology is deeply tied to their historical experience with the HIV crisis. At the time, local authorities, motivated by economic gain, withheld information about HIV, causing many villagers to miss the opportunity for timely medical treatment. This history fostered a deep mistrust of the local government among the villagers with regard to healthcare and COVID-19.

Scenes from the village in Henan where fieldwork was conducted. [Image credit: Author]

Producing lay knowledge under the “zero-COVID” regime

Under the “zero-COVID” regime, the Health Code (jiankang ma, 健康码) had become a critical instrument for tracking infection risks and implementing epidemic control measures during the pandemic. However, the villagers in Henan province were left uninformed about its mechanisms of how it connected infection status to subsequent epidemic control measures such as lockdowns. As a result, whenever lockdowns occurred, villagers often assumed that they were caused by villagers who had previously been infected with the Delta variant. Moreover, they were unaware of potential technical malfunctions regarding testing and treatment.

This lack of knowledge related to epidemic control measures strengthened the villagers’ reliance on lay knowledge about COVID-19 infection. Thus, when the Delta outbreak occurred in 2021, the local official narrative that COVID-19 patients were no longer contagious after treatment was met with skepticism among uninfected villagers. They drew parallels between COVID-19 and HIV, believing that the new virus, like HIV, remained in the body forever. The result was a belief that recovered COVID-19 patients were perpetually contagious.

Lived experience of previous health crises shaped attitudes towards COVID-19 survivors in Henan. [Image credit: TA design / Adobe Stock]

From the perspective of individuals who had recovered from COVID-19, however, their mistrust was directed at the government’s diagnosis of their infection. Their symptom-free physical experience and subsequent treatment led them to question whether they had ever truly been infected. This added to their sense of unjust treatment in their village, which they expressed as frustration with the stigma experienced from peer villagers.

Together, these two perceptions (of perpetual infection and misdiagnosis) were products of China’s unique “zero-COVID” regime in combination with previous experience of local health crises related to HIV. The government’s approach, coupled with strict information control, restricted access to broad sources of knowledge about COVID-19. In this context, deeply rooted mistrust of the local government led villagers to rely on their lived experiences and historical memories of the HIV crisis to understand COVID-19.

Concluding remarks

The lay epidemiology of villagers in Henan province was not merely a form of knowledge rooted in local culture and lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was also a product of epidemic governance penetrating the villagers’ everyday lives. In Chinese society, science is subordinated to party-state governance and deployed as a technique of governmentality. Lay understandings of emerging infectious diseases thus inevitably intertwine with the practice of science as a tool of governance. Moving beyond the debate over whether laypeople can challenge scientific authority, my research suggests the need for more critical inquiry into the complex dynamics between locals and official powers across different cultural contexts.

Siyi Chen is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Tsinghua University in China. Her research interests include medical anthropology, sociology of science and expertise, work and profession.

Published: 08/18/2025