The Energy Fictions of Cure and Dependency

Emerson Cram09/22/2025 | Reflections

Note on content and language: This reflection engages archives of 19th century state asylums in the U.S., and some readers may find its content triggering. Specifically, I discuss “work therapies” in asylums as an imagined cure for psychiatric disabilities. I also use language outdated by contemporary standards, but critical for interpreting the historical context of their use, including how these terms circulated as connected to regimes of race, class, disability, gender, and sexuality.

Can energy enliven political ecology’s relationship to disability? I’ve been lingering with this question as I feel through remnants of poor farms, state asylums, and other carceral institutions negating “abnormal” dependencies. Prominent sociologist John L. Gillin elaborated this social problem: “abnormal dependency may be defined as that condition in which a person prefers to depend for his sustenance, in whole or part, upon someone other than his natural supporter rather than to earn his own living. He is a dependent without an independent spirit” (Gillin, 1937, p. 21). Sustenance implies an energy exchange critical to sustain life, and Gillin’s ire toward “unnatural” public institutions can otherwise be interpreted as maladjusted energy. This is an example of what I call energy fictions, cultural stories about the immaterial value of work, from demonstration of moral personhood to one’s proven capacity for self-sufficiency. Deeply rooted in settler colonial governance of human and non-human life, energy is a language of transformative potential—in which matter is transformed as useful for capitalist value (Cram, 2022). I’ve found how agricultural, occupational, and care labor in institutional settings were touted for “therapeutic benefits,” as inmates were expected to complete farm chores, weave rugs, or attend to residents.1 As “therapeutic” narratives, energy fictions are consequential because of their promise of cure, and their residual power remains (Clare, 2017; Kafer, 2013). Energy fictions capture scenes of individuals harnessing measurable productivity as a cognitive and physical capacity “rescued” from real or perceived impairment. Since 2019, I have tried to make sense of these stories through the Johnson County (Iowa) Historic Poor Farm, first established in 1855. As the site now narrates, stewards provided “care” to both “paupers” and the “pauper insane,” two deeply stigmatized classes of people who “could not support themselves.”

Independence State Hospital's museum displays a dress that female patients would have helped sew and later wear. [Image credit: Author, 2024]

A member of the public walks past the historic asylum building at the Johnson County Historic Poor Farm. Built in approximately 1861, this building housed the "insane" until it was repurposed in 1880s. For roughly the next 90 years, it would be used as a hog house until Supervisor Robert Burns called for its preservation for educational purposes. [Image credit: Author]

The intellectual and scientific class imagined dependents in moralizing economic terms, as “burdens” on an industrializing nation. In this context, energy fictions were seductive for their promise to eradicate “waste.” Charitable and correctional institutions were centralized to intervene in dependency, delinquency, and degeneracy’s social and economic “costs.” The politics of what Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon (1994) have called “industrial dependency” instilled waste as a primary metaphor of economic potential and risk to national futures. Disability historians document powerful narratives of moral citizenship through social welfare’s cultural fantasy of productivity, but rarely if ever take up questions of energy (Rose, 2017; Nielsen, 2019). Asylum and poor farm inmates were broadly tasked with gendered labor, divided between physical agricultural labor or tasks most rendered as “domestic.” In both, land is labor’s precondition for energy’s modulation. On the other hand, critical genealogies of energy have much to say about industrial fantasies of productivity and the multi-scalar transformation of nature, but do not explicitly engage with matters of disability (LeMenager, 2013; Daggett, 2019; Wright, 2025).

In my book and podcast projects emerging from the past six years and ongoing archival research, community-based teaching, and site interviews, the land teaches me how land tenure systems are conditions of possibility for expanding institutions’ reach, the movement of people through pathways of diagnosis or criminality, and soil for labor’s “cure.” The loss of, or at times the refusal of “legally bound” family members, was one of the primary conditions for institutionalization. In Iowa of 1855, the family was legally liable for the care of those seeking public relief support, and counties would exhaust a search for the legally bound payor prior to distributing relief (Gillin, 1912, p.50). Some arrived at poor farms because of the desertion of marriage or because relatives refused the legitimacy of their relationship. The gendered demarcation between “farmers” and “farmer’s wives” was potent enough that at least one individual known as “Happy George” masculinized themselves through dress to gain access to men’s relief work. The volatile economic environment of territorial and early statehood Iowa made individual access to land extremely challenging for most, whether through initial patents, or deeds inflated by ongoing land rushes, speculators, and railroads, not to mention “Black Codes.” I’m continuing to wonder: how did the divisions between landowners and tenant farmers or laborers contribute to the production of need for poor relief, and how did people resist these conditions

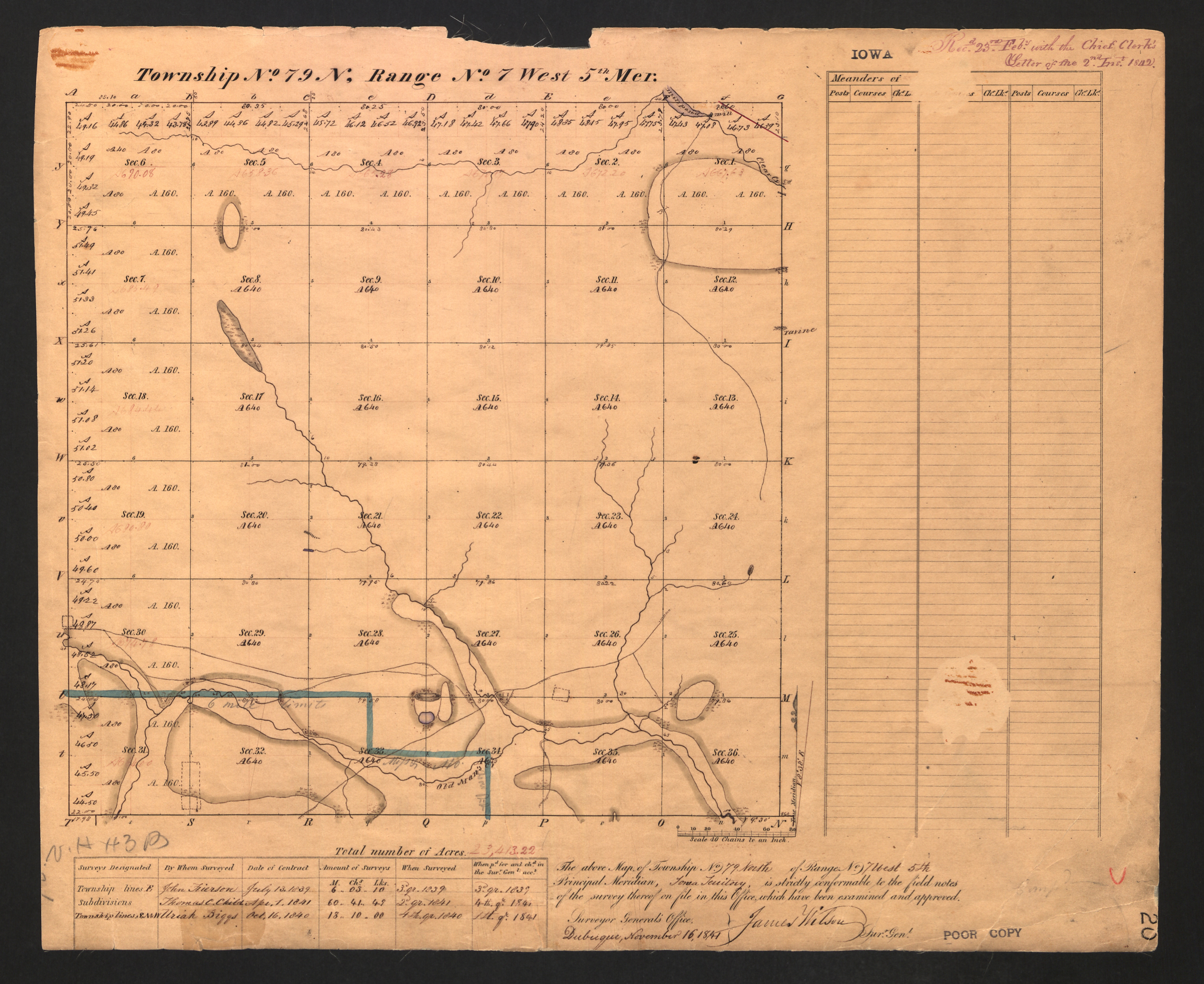

Original survey of Union Township, Approved in 1841. Many of these sections were originally claimed as "Bounty Land Warrants," by military officers or their heirs, from fighting in the War of 1812, the Revolutionary War, or the Mexican-American War. Source: General Land Office Records. [Image credit: Author]

By contrast, the state (in the case of hospitals, prisons, and reform schools) or its county entities (in the case of poor farms) easily acquired lands to expand institution numbers as their respective populations soared. Social reformers called for the increased surveillance and segregation of classes of people. The state’s authority over dependent classes transcended sheer diagnostic power, to expand to relations of property and land tenure after declaration of legal insanity by county insane commissions. As disability historian Kim Nielsen (2014) argues, competency hearings could adjudicate one’s “fitness” based on management of resources, and probate courts had authority to manage estates (i.e. land or other property) through assignment of guardianship. For those not yet marked by “heredity,” work was an occupation to counter restless preoccupations. Work—so the story goes—could restore the optimal fantasy of self-sufficiency and the hygienic management of energy (Cram, 2021; 2022). However, I have yet to encounter a case in which this fiction also restores an individual’s personal claim to land.

Gender Labor as Therapeutic Energy

The Board of Control for State Institutions (The Board) encompasses one of my central archives. Created by the state legislature in 1898, The Board newly assumed all authority over Iowa’s vast institutional network. Diminishing counties with asylums or existing trustees, they asserted themselves as sole authority of the state’s “insane.” The Board’s authority expanded amidst increased calls for economic centralization, alongside asylum-based psychiatry’s increased pressure to legitimize their work in formidable professional debates.2 Their yearly publications detail some of these deliberations and capture how the politics of dependency intersects with medicine, botany, agriculture, animal husbandry, and institutional management. I’ve chosen to focus the remainder of this reflection on a close reading of select passages that depict mechanics of energy.

Nearly every mention of inmate labor names therapeutic and economic incentives. Early influences could have included Thomas Kirkbride’s “moral cure.” “Labor is one of our best remedies,” he argued, noting how farming and gardening offer “useful occupation to the insane at certain periods of the disease…” (Kirkbride, 1854, pg. 62, emphasis mine). Kirkbride does not emphasize gardens as a type of “exposure” (i.e. fresh air), but rather, his focus remains on occupation. Of note is the doubling of occupation as diversion of attention and energy from unwanted matters, and as a type of worker. Occupation (attention) can be realigned from extremes, between restless or excited. But the value of labor, he adds, also is metabolic: it “promotes a good appetite and a comfortable digestion.” However, this example does not tell us much about the literal or metaphoric mechanics of energy as they interface with “therapeutic” labor.

/>Inside the "Farming Room" of the Independence State Hospital Museum, which predominantly features narratives of patient chores, food production, and the hospital's Holstein breeding data. An undated newspaper headline reads: "Automation To Take Over Milking Chores at Modern MHI Farm." [Image credit: Author, 2024]

In one telling example, Dr. Max E. Witte contextualizes “insanity” as a matter of in/voluntary attention remedied through manual labor. Witte proclaims, “Now, it is through diverted attention that manual labor does good to the insane, and gives rest to the tired brain, deranged in its activities, by setting certain uninvolved motor centers in operation and drawing the excessive flow of blood away from overworked, exhausted and irregularly operating centers” (Witte, quoted in “Bulletin,” 1899, pg. 115). In a longer passage, Witte argues that for agricultural and laboring classes who predominate at state hospitals, “work on the farm and in the garden should be more extensively employed.” The beneficiaries of said work, Witte claims, are patients (therapeutic), but the positive impact to institutions themselves can’t be denied (economic). At the heart of the claim is the assertion that “expend(ing)” energies “in irrational or mischievous motor activities are benefitted by their employment” elsewhere. Labor can repair independent will.

Witte touches one central dispute: should patients be mentally occupied with the work of their primary occupations? Should the farmer farm? The seamstress sew? Concerns about monotony are revealing. Some at the table noted the monotonous work of farming–for both farmers and their wives–and this alone requires different occupations of time. For those who have the potential to be restored to future productive potential as labor (i.e. the curable insane), energy is a language of transformation, and conversion. It is a logic that produces the curative fantasy of the asylum. And yet, for those who are marked by scientific charity’s proclamation in “hereditary” losses, those inmates must be further segregated and subject to eugenic marriage and/or sterilization (Whatcott, 2024). Recalling Gillin’s characterization of abnormal dependency, the eugenic unit of the family is the naturalized social form for sustenance, and a keeper of the integrity of independent willfulness.

GROW Johnson County's cultivation fields that include marigolds, basil, and white eggplant at the end of the growing season in 2024 [Image credit: Author, 2024]

These are some of the origin stories of “dependency” as an energetic drain, a potent reservoir of anti-welfare sentiment that flows through contemporary debates about what people or forms of care are “burdensome.” Disability studies and communities will continue to be on the forefront of resisting these negative valences of dependency. For a disability justice resistive to state violence, dependency can be a language of need; it is “the cultivation of radical interdependency, and the recognition of the numerous support systems on which survival depends” (Kim, 2025, p. 2). In the face of the relentless politics of deprivation in 2025, I like to think that the land and its soil is keeping the survival stories of those who labored here so long ago. The local food projects the land now sustains are feeding many, using non-profit systems on public land to cultivate foods that meet cultural needs and hungry bellies. To the county’s food and farm manager, I described this work as “community life support.” And when we–the farming volunteers and staff–head out in the early mornings in the growing season to cultivate, weed, and prep an assortment of okra, roselle, cabbage, and sunflowers for delivery to local pantries, we are giving our energy to the simple fact: “to need is to be alive” (quoted in Nishida, 2022, pg. 1). We are regenerating these soils and their yet to be known energy futures, restoring relations of mutuality between people and planet. We are attending to need in all forms, seeding these grounds of radical possibility, and holding dreams of abundance.

Author Bio

Emerson Cram, PhD is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Communication Studies and Gender, Women’s & Sexuality Studies at the University of Iowa. They are the author of the award-winning book Violent Inheritance: Sexuality, Land, and Energy in Making the North American West (University of California Press, 2022). The related podcast “Disability Ecologies” will debut in 2026. This post draws from a book in progress provisionally titled, Regenerating Mad Ecologies.

Editors Comments

Ashton Wesner edited this post with assistance from Aaron Gregory.

2. For an example of the “explosive” moment between psychiatry and neurology, see Silas Weir Mitchell’s address to the 50th meeting of asylum superintendents at the American Medico-Psychological Association in 1894.

Published: 09/22/2025