Chronicity and Its Social Lives: Reflections on Everyday Experiences of Osteoarthritis

Perseverence MadhukuMichaela Clark edited this post.

11/07/2025 | Reflections

Introduction

What does life feel and look like when a once active body breaks down, when pain and emptiness become the contours of everyday existence? How do patients, families and societies perceive chronic illness associated with ageing?

Osteoarthritis is a painful, degenerative, and incurable joint disease characterised by knee inflammation, swelling, and deformed joints. It is often described in biomedical terms as a disease of loss: the wearing down of cartilage, the stiffening of joints, the decreased mobility. Yet, osteoarthritis is not only a biological condition but also a deeply social and cultural experience. In this sense, I propose following Margaret Lock’s call to contextualise interpretations of the body. As she argues, the ways ageing and incapacities of the body are experienced and narrated are shaped by specific local histories, knowledge, and local biologies. In many contexts, individuals experience the degeneration caused by the disease in terms of improvisation and negotiation – efforts that make immobility liveable. In this post, I share insights from individuals living with osteoarthritis in Zimbabwe and demonstrate the tension between biomedical, social, and personal understandings of ageing, immobility, and care.

More than what machines can see

One afternoon, Tsitsi, my host, told me about an elderly woman named Hilda who lives in their village. Tsitsi seemed upset and astonished by Hilda’s situation: “Ava here, havafi, vakateya riva!” (this one, she will not die; she trapped death). Hilda has been living with osteoarthritis since 2014.

Hilda explaining aspects of her experiences with osteoarthritis. [Image credit: Author]

Villagers nicknamed Hilda mufandichimuka, deriving this from the name of a popular indigenous herb, myrothamnus flabellifolius. The plant is known for its resilience to extreme weather conditions — appearing lifeless and shrivelled during dry periods, only to be revived with moisture. Hilda’s nickname reflects the multiple meanings of osteoarthritis as both a source of stigma and a symbol of resilience. Many of her neighbours believe she performed a powerful death-averting ritual, known as kuteya rufu neriva, which literally translates to “courting death with a trap.” In the Shona cosmology, an individual who performs such a ritual is said to be capable of cheating death several times.

Osteoarthritis in Zimbabwe is deeply intertwined with accumulated life experiences. The everyday language focuses on a distinctive temporal framing that sharply contrasts linear narratives of disease progression. Metaphors such as muviri rave dongo (the body is now a ruin) and chikwereti chezera (age’s debt) situate degeneration within layered, cyclical, and socially embedded temporalities. The body here is defined beyond the machinic model of biomedicine, instead formulated as a lived and historical entity. Framing osteoarthritis as a “debt” suggests that bodily deterioration is meaningful, inevitable and even an honourable consequence of resilience across life stages. Such a perspective invites us to think about time as recursive, where the past, present, and future coexist in narratives of chronic illness.

Even so, medical doctors in Zimbabwe prescribe pain-relieving medicines and encourage osteoarthritis patients to attend physiotherapy sessions. Yet, Hilda’s repeated assertion, “you do not understand, machines cannot see everything,” speaks to the gap between her lived experiences and the clinical framing of osteoarthritis. Contrary to the medical records, she situates the genesis of her illness to significant life events—notably the death of her husband and the ensuing disagreements over inheritance. This understanding challenges biomedical explanations that privilege clinical signs while relegating patients’ voices and contextualised experiences to the margins. Medical records, medicines, and physiotherapy offer Hilda one among multiple competing truth claims about osteoarthritis.

Care and its moral conundrums

Osteoarthritis highlights the intimate and often unspoken negotiations of care and illness beyond the clinical gaze. Patients frequently describe their pain in ways that reflect embodied histories, social relationships and moral worlds rather than biomedical categories. Likewise, caregiving takes shape in gestures, routines and the negotiations of daily life between patients, their relatives, and lived environments. These practices reveal how osteoarthritis is lived as a social and affective phenomenon.

A conversation with Lilian at her homestead. [Image credit: Author]

Lilian crawls every morning, when her “knees permit”, to sit outside her hut—a location that allows her to view the graves of her late children and husband, as well as anyone approaching her homestead. Crawling is a skill that she painstakingly taught herself over several months in defiance of her children’s suggestion to purchase a wheelchair as a mobility aid. While her children view the provision of this medical technology as a form of care, Lilian perceives it as an admission of defeat and a loss of dignity.

For Lilian, care is nuanced and includes proximity to the graves of her kin and self-trained daily routines. Indeed, she continues to resist her children’s wish for her to relocate to the city, which would allow her to be in proximity to hospital facilities. Where her children imagined care for and safety of Lilian through access to clinical resources, Lilian herself raises the moral conundrum of intimate caregiving that would come from this spatial shift:

The ethics of who may handle the body or its excremental and other bodily discharges are never neutral but charged with kinship boundaries. Kinship ties structure expectations and obligations around caregiving, where individuals outside the kinship network, such as daughters-in-law, may not be expected to take on intimate care duties. Although part of the family, a daughter-in-law cannot take care of their immobile mother-in-law or see their nakedness. Here, care is an intimate practice shaped by social relations and patients’ experiences of chronic illness. The idiom of mutorwa reframes care—a stranger’s labour must be compensated.my daughter constantly travels for her community health work. Do you know who will feed, bathe, and take my soil out? Their daughter-in-law. This is unacceptable! She is a mutorwa (stranger). Where do I get the cow to compensate her if she touches my soil and my blood? I would rather die here. I am not alone, as you can see (pointing to the graveyard); my other children are over there.

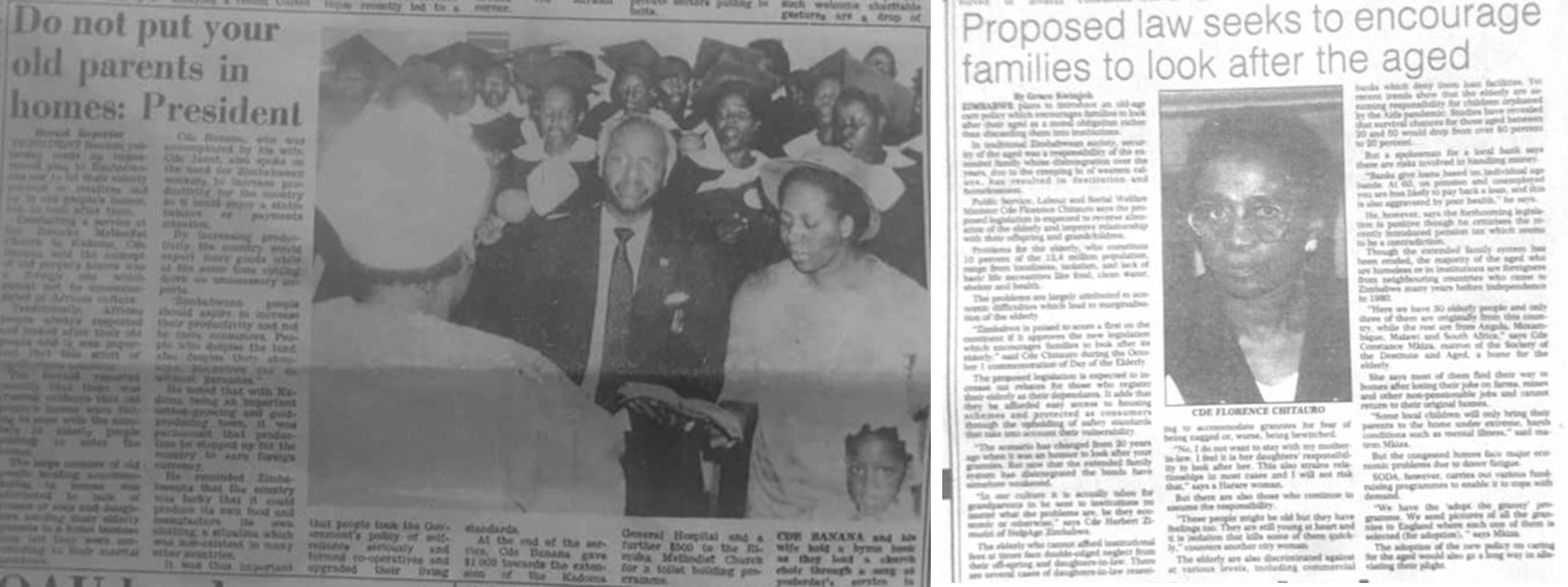

Newspaper articles in The Herald titled “Do not Put old parents in Homes” (23 October 1987) and in the Sunday Mail titled “Proposed law seeks to encourage families to look after the aged” (19 October 1997) demonstrate the ‘un-African’ framing of care homes for the elderly and immobile. [Image credit: Author]

Newspaper articles in The Herald titled “Do not Put old parents in Homes” (23 October 1987) and in the Sunday Mail titled “Proposed law seeks to encourage families to look after the aged” (19 October 1997) demonstrate the ‘un-African’ framing of care homes for the elderly and immobile. [Image credit: Author]Yet, sending older parents to care homes is considered as kurasa (discarding). It is “unthinkable” for Lilian’s family as it would invite ridicule, and, in the local moral world, it brings munyama (bad luck) upon the children and their descendants. The idiom chirere mangwana chigokurerawo (loosely translated to “nurture a child, she will nurture you tomorrow”) obligates children to care for their aged family members. The government consistently reinforces the notion that placing the elderly in care homes is “un-African.” This cultural rhetoric allows the government to evade its role in developing institutional support for the aged.

Concluding remarks

Osteoarthritis invites a rethinking of chronic illness beyond its medical contours, foregrounding the social, cultural and moral worlds in which bodily degeneration and care are embedded. This post underscores the importance of attending to patients’ voices and contextual negotiations that make chronicity liveable. These ethnographic vignettes show the layered entanglements of biomedical care and situated knowledge, reconfiguring what it means to inhabit a body with osteoarthritis.

Perseverence Madhuku is a PhD candidate in African History at the University of Bayreuth and a Junior Fellow at the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS).

Published: 11/07/2025