The bush turkey among the cats: misrecognition, modifications, and expertise in AI-operated lethal cat control

Mardi Reardon-Smith12/08/2025 Reflections

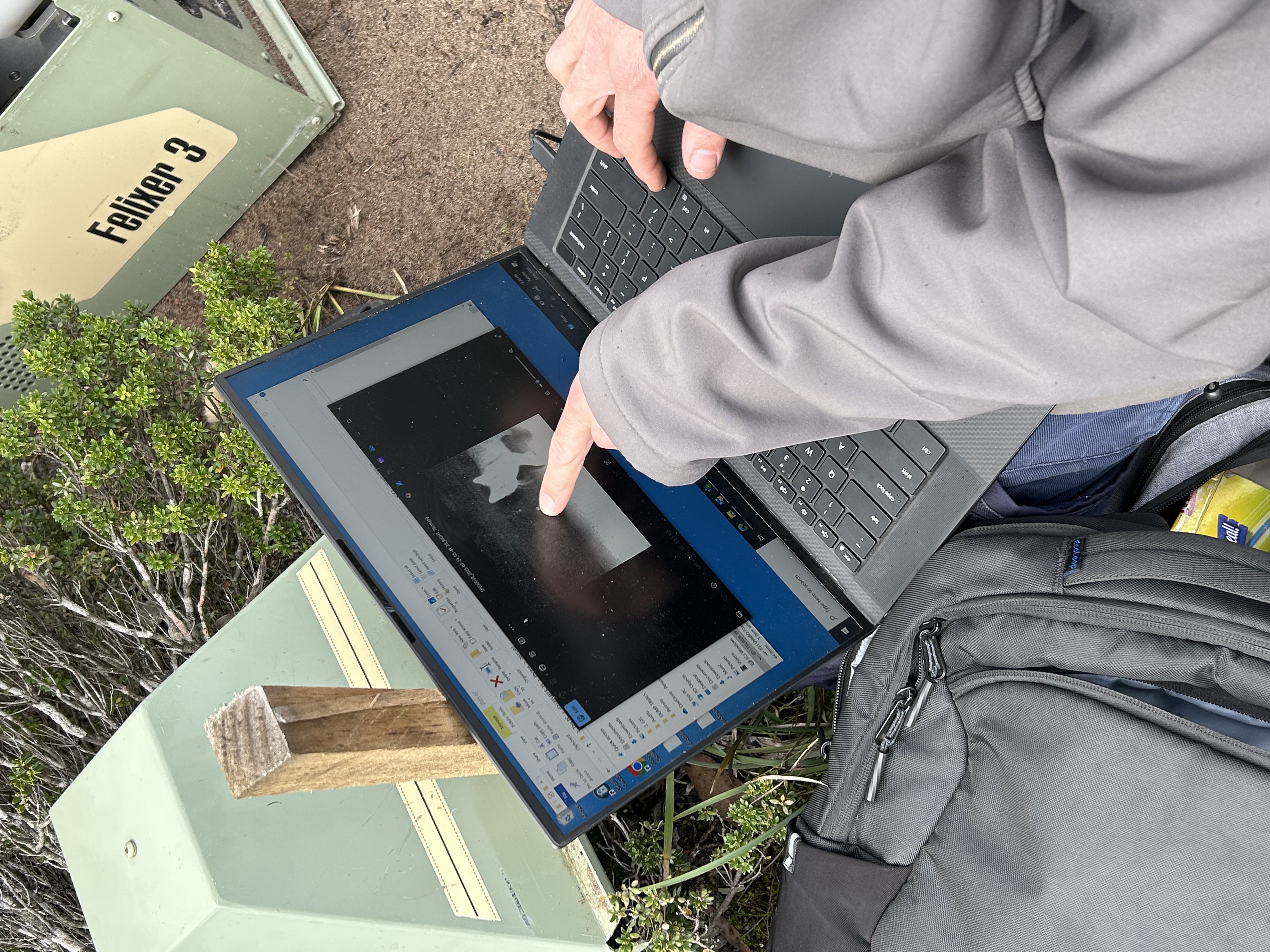

Image caption: A Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger sets up a Felixer in the Wet Tropics region of northern Australia (image by the author)

In the middle of a tropical rainforest, I am standing in a small clearing watching a park ranger repeatedly drag a shovel across the damp earth until he is confident that the ground is ‘laser level’. He is meticulously preparing the site so that he can employ an autonomous cat-killing machine called the Felixer. The Felixer is a stationary, automated grooming trap that identifies cats using a mixture of LiDAR sensors and an AI camera to shoot cats with a gel that contains the 1080 toxin. It exploits cats’ behavior as fastidious groomers to function, as cats will invariably lick the gel from their fur, ingesting it and dying a short time later. While ostensibly an ‘autonomous’ technology, for practitioners Felixers are anything but ‘set and forget’. Their success relies on practitioners having a highly refined skillset, being able to adapt and modify hardware, and possessing detailed knowledge of cats and the landscape.

Conservation tech and feral cat control

In an increasingly automated world, new technologies are being brought to bear on environmental issues. Surveillance technologies, initially designed for use in the military, have been repurposed for environmental monitoring and data gathering. Enormous data sets are being analyzed using artificial intelligence, and tools in the field are being fitted with AI capabilities with the goal of improving efficiency and efficacy. Beyond monitoring and research, new and emerging technologies are being put to work in the control of invasive species. The effects of these new tools and technologies are, potentially, transformative.

A particularly significant invasive species for Australia in terms of biodiversity loss and mammal extinction is the cat (Felis catus). Classified variously as feral, stray, or domestic, cats kill an estimated 2.5 billion native animals each year in Australia through predation. Australia’s federal government announced a ‘war on feral cats’ in 2023, and – relatedly – a slew of funding for the development of conservation innovation to tackle the problem of cats. Posited by some as possible ‘silver bullet’ solutions to environmental issues, new technologies (like the Felixer) articulate with and – in fact – are only made to work through their entwinement with existing forms of labor, expertise, knowledge, and care.

Feral cats and the damage they cause to native animals and ecosystems are widely acknowledged as a problem demanding response. As with many conservation projects, feral cat control is a necessarily biopolitical regime, functioning at the level of the population. Feral cats are controlled so that other, vulnerable species, may avoid extinction. Feral cat management has traditionally involved trapping, baiting, shooting, and the use of exclusion fencing to keep cats away from threatened species. While feral cat eradication is effective for improving the outcomes for vulnerable species (for instance, where cats can be removed entirely from a predator-proof fenced area, native species like bilbies are able to re-establish robust populations), the benefits of control programs that do not significantly reduce the number of cats in a given area are more ambiguous. Part of the reason for this is the difficulty of accurately monitoring species, and - in particular - monitoring and modeling for cats who are a notoriously cryptic species. Nonetheless, practitioners who are aware that many native species are on the brink of extinction tend to operate under an assumption of urgency, choosing to direct their efforts towards action rather than research.

Scientists and practitioners in this space are eager to find and develop tools that have the capacity to work at scale, and to control cats in the most humane way possible while reducing impacts on off-target species. While Felixers are not a landscape-scale tool, they are able to deliver a toxin to cats in a more controlled fashion than techniques like baiting; further, many native animals in Australia are not susceptible to the toxin that is used (1080, or sodium fluoroacetate).

The Felixer: trial, error, and fixes

The Felixer has been on the market for around a decade. Initially designed for use in the arid zone, early versions of the tool ran off LiDAR sensors alone which fed into a series of algorithms that allowed the machine to identify a ‘cat-like shape’ moving in a ‘cat-like way’. Transplanted from its desert setting into places like the maritime environment of Kangaroo Island or the lush tropical rainforests of far north Queensland, practitioners began tracking incidences of off-target firings. Felixers were mistaking all sorts of things for cats; koalas, bush turkeys, wallabies, and lambs have all been fired upon. It turns out that quite a lot of animals can present as a cat-like shape moving in a cat-like way.

To combat this, the makers of the tool retrofitted the units with an AI camera which can recognize cats. The use of AI for the recognition of non-human species – and sometimes individual members of a non-human species – has been developed in recent years for the purposes of monitoring species and, in this case, to achieve specifically necropolitical ends. As Emily Wanderer has noted, the issues raised around the ethics of facial recognition AI for humans are generally absent in discussions around using these technologies to identify animals. But using facial recognition to mete out lethal control raises complex questions and concerns.

Image Caption: A cat photographed by a Felixer prior to being fired upon in the Wet Tropics region of northern Australia (image courtesy of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service)

The AI-operated Felixer has been used with varying levels of success across different regions of Australia, and in a diversity of ecosystems. Due to the variation in ecosystem types across Australia, practitioners - including rangers, ecologists, and land managers - must train the AI in each new setting to avoid misrecognition. Generally, practitioners will utilize the trap in the camera-only mode for several months until the trap is no longer misrecognizing off-target species, and only then will the trap be switched to ‘active’ mode. For some practitioners, the level of input, time, and expertise required leads to a frustration towards what many assume is an ‘off-the-shelf’ product, ready to be put to use. As one National Parks employee told me, ‘everyone wants the output, but no one wants to train the algorithm.’

Further, different issues emerge with the hardware in different settings. In the tropical rainforest I mentioned earlier, the ranger there modified his unit with a larger solar panel and battery pack, so that the machine could work in the low, filtered light of the rainforest. He designed and assembled an aluminum rig for the unit to sit upon, to deal with the soft and uneven, muddy terrain. Finding that the heavy rain that the region experiences throughout the year was splashing the camera and sensors with mud, he began placing the unit on a large piece of artificial grass to minimize the risk of mud splatter.

What the experiences of these rangers demonstrates to us is that the technosolutionist promise of conservation technologies (that they will be transformative for reducing labor requirements, that they will increase efficacy exponentially) does not necessarily bear out on the ground. Instead, these tools are only made to work through the expertise, care, labor, and tinkering of rangers and ecologists. The mission-driven nature of conservation means that the field is susceptible to hype and desirous imaginings of a ‘silver-bullet’ solution. However, for practitioners like the rangers and ecologists carrying out these cat control programs, there is an acknowledgment that there is not, and perhaps will not ever be, a purely technical solution to the issue of feral cats.

Image caption: A Park ranger sets up a mount for the Felixer in northern Australia (left); An ecologist looks through the camera images captured by a Felixer on a South Australian island (right) (images by the author)

AI, automation, and human-environment relationality

I am interested in the Felixer because it can help us to tease apart interesting questions about what automated technologies and artificial intelligence do to human-environment relationships in environmental management. As commentators have pointed out, while many practitioners are enthusiastically embracing the use of AI in conservation, others are wary of what such hype obfuscates. The day-to-day reality of using a tool like the Felixer is one of ongoing care, maintenance, and tinkering. Applying automated tools and AI to conservation does not, as may have been hoped, ‘take the human ‘out of the loop’’.

But what does the Felixer do to the relationship between environmental management practitioners and cats? And how does it transform how they are thinking about and carrying out their work? These are questions that I will take up as I investigate the Felixer alongside a range of other tools and technologies in the cat death-space, including image recognition software, networked trail cameras, trap alert systems, and audio deterrent devices. Building on my previous work on invasive species and killing as a form of care, I am exploring the affordances and constraints of new tech in this space for invasive species control, and for human-environment relationality more broadly.

Mardi Reardon-Smith is a postdoctoral researcher with the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S) in the Emerging Technologies Research Lab at Monash University. Her research sits within environmental anthropology and science and technology studies (STS) and investigates the social dimensions of environmental management in intercultural and settler-colonial contexts. Dr Reardon-Smith has published on topics including the joint management of protected areas, the co-creation of environmental knowledges, and human relationships to invasive species and their control. She is the author of Making Do: Conservation Ethics and Ecological Care in Australia (Stanford University Press, 2025).

Published: 12/08/2025