Designing Natural Things: How Images Make Meaning in History of Science

Mackenzie Cooley, Anna Toledano, Duygu Yıldırım

May 8, 2023 | Projects

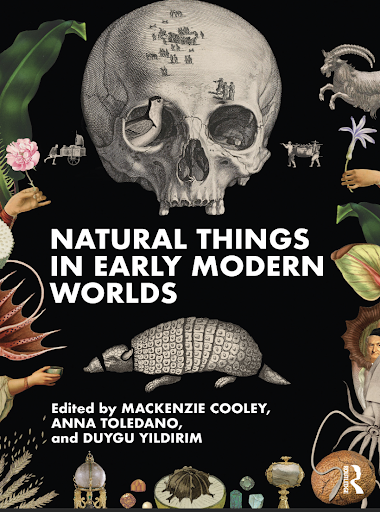

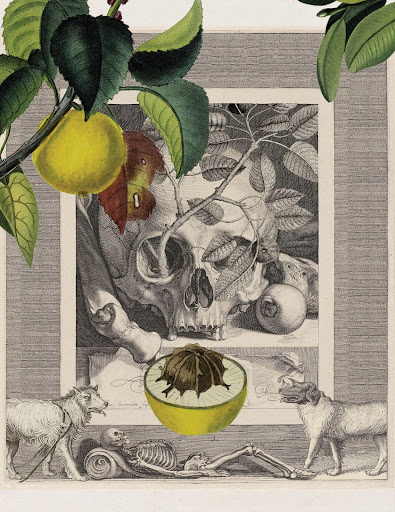

Cover, Natural Things in Early Modern Worlds (Routledge, 2023).

How do you capture the essence of a history about monstrous squids and the shipmates who ate them, and poisonous manchineel trees? Using text to set the scene is one thing. Taking seriously the visual record left in the wake of these histories and using those elements to create something new is another. Since founding the Natural Things research group at Stanford University in 2015, we have been wrestling with the connection between design work and natural history. When it comes to premodern sources, European natural histories are some of the most lavishly illustrated texts found in the scientific oeuvre. Authors and artists often worked together to create images that would allow readers to identify plants, animals, and minerals for themselves. Our musings slipped into a question: How did premodern scholars of nature think through images, and how could we echo that process in a way intelligible to today’s readers?

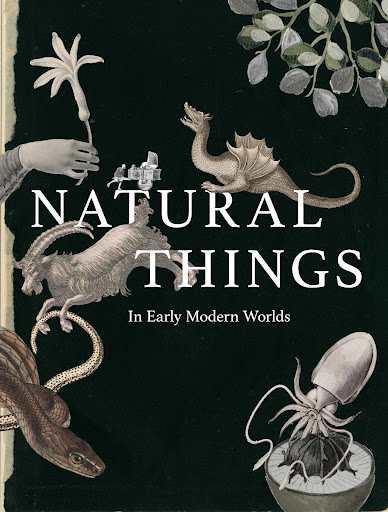

Alternate Cover, Natural Things.

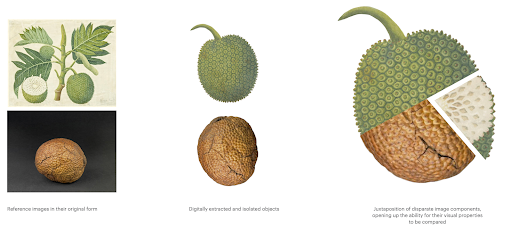

Alas, historical thinking—no matter how broad—can only do so much. This is when interdisciplinary perspective really matters: enter designers Katie Dean and Zoë Sadokierski. We had been drawn to Dean’s gorgeous visual experiments using digital collage. These visions took flora and fauna from natural histories and eighteenth century artworks and brought them into a new place. She transformed seeds and flowers extracted from watercolors into new, blossoming botanical structures. This process of thinking with images was, we thought, not unlike what early modern naturalists did: through a process of creative decontextualization and recontextualization Dean spotted new patterns in nature. The Roman naturalist and collector Cassiano dal Pozzo had done something similar in his collaboration with artists to make a “Paper Museum” of thousands of images of the natural world. Dean brought in Sadokierski, an award-winning designer and Associate Professor in Visual Communication at the UTS School of Design, who contributed not only a nuanced visual perspective but her commitment to communicating biodiversity loss and climate transitions. Her work plays with hybridity and change and captures the dangerous dynamic of human influences on the natural world.

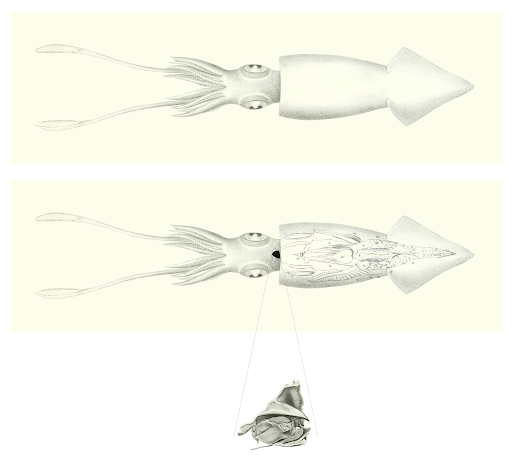

Making “Ambergris.” The collaged images behind the visual experiment for Kate Biedermann and Mackenzie Cooley’s Chapter “Ambergris: From Sea to Scent in Renaissance Italy.”

Then, we invited scholars—especially junior scholars—working on similar topics to collaborate with us. We started the conversation through a working group in History and Philosophy of Science at Stanford, inviting a number of researchers to join us in California to share their work on topics from materia medica to botanical specimens to anthropological remains. From there, we developed a call for papers for the History of Science Society Conference in 2017, which resulted in two robust panels (Natural Things and their Environments: Early Modernity and Natural Things Beyond their Environments: Modernity and Alienation) and many more papers we wished we could have included in those conversations. We hosted a book conference at Hamilton College in April 2019 where invited contributors identified the major themes of the project. There, a group of scholars polished their histories of how natural knowledge and practices were messily exchanged, translated, repurposed, and sometimes lost along their journeys from Mesoamerica to Madrid, Borneo to Britain, and China to France.

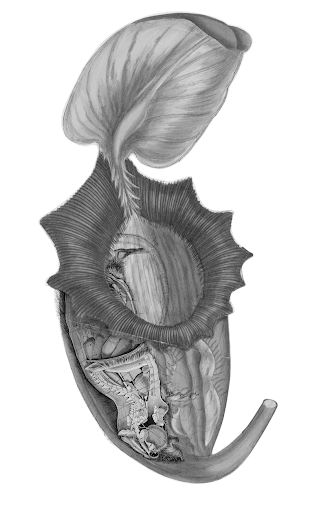

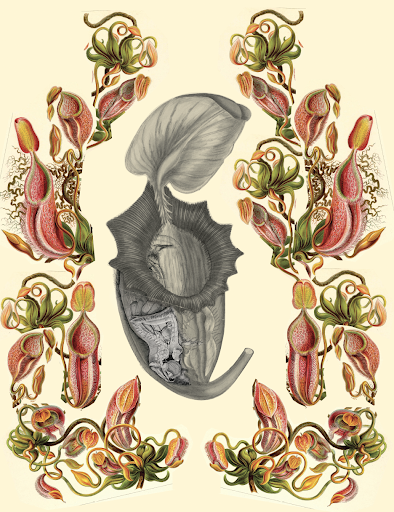

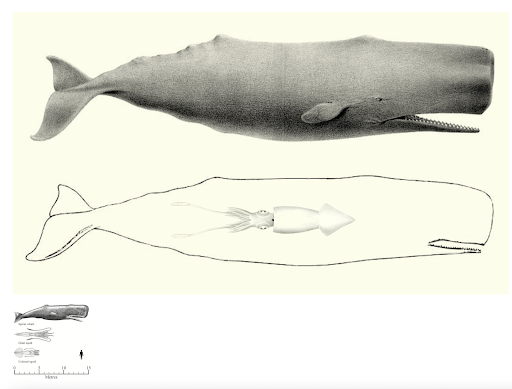

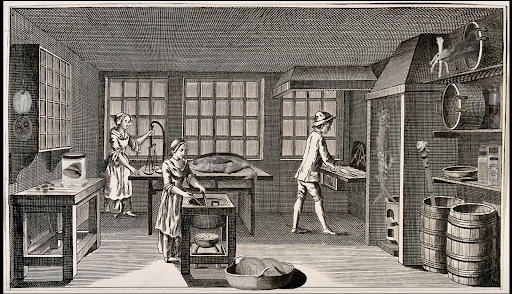

The text of Natural Things in Early Modern Worlds emerged from these collaborations. Then, the question became how to effectively bring together designers and researchers. Dean and Sadokierski corresponded and met with our authors and asked them each to provide links to images that captured the nature of their archives and the content of their chapters. They ultimately selected a single sentence and developed a visualization that responded to it. As they write in their book section “On the Design,” “Rather than providing visual evidence or visual summaries of a particular aspect of the written text,” the visualizations they created “are visual provocations; they are deliberately complex, ambiguous, and often surprising, inviting readers to critique the way the archival material is visually represented in scholarly publishing, and the inherent bias embedded in the process of creating images” (15). The digital collages, then, became unsettling images that, in Sadokierski and Dean’s words, meant to “unsettle viewers’ expectations of what a natural history illustration should look like, to prompt discussion around the way images are constructed and shared” (16). When early modern naturalists represented the living world around them, they created a style of scientific certainty. These contemporary collages “call attention to the fact that all images are fictions” (16).

Playing with Pitcher Plants. The Evolution of the Visual Experiment for Elaine Ayers’s Chapter “Pitcher Plant: Drowning in Her Sweet Nectar.”

Collaging requires a corpus of existing visual material that artists can access and manipulate digitally. Therefore, the visual experiments in this book tend to use images created by our historical subjects: those engaged with early modern nature studies. However, the distinctive character of different primary sources determines the limits of these experiments, meaning usage and frequency of visualizations change across different archives. While epistemic images illustrate the close relationship between visual arts and natural history in the European context, finding similar engagements in the early modern Ottoman World is much less common. In this book, the remaking of these distinctive visual primary sources offers new insights into the process of how historical actors came to different interpretations of the very same sources. Despite their commonality in the intertwined histories of European art, science, and colonialism, such images were not simply representations of natural things. Any representation of a natural thing, built in ambiguity, had already undergone a process of alienation. It was the reader’s responsibility to think through and resolve these uncertainties, which led to various scientific and cultural debates across time and space.

Squids, Whales, and Breadfruits. Selecting Images of the Sea.

Visual Experiment for Whitney Barlow Robles’s Chapter “Squid: Natural History as Food History.”

For the historians who contributed chapters to the book, such a close collaboration with designers was, by and large, a new experience. Whitney Barlow Robles’ chapter explores how nature studies overlapped with the crafts of cooking and consumption. Her research for the Natural Things project led to a digital spin-off exhibition called The Kitchen in the Cabinet: Histories of Food and Science, produced in collaboration with Katie Dean and three Dartmouth undergraduate researchers–Lauren Dorsey, Fatema Begum, and C.C. Lucas.

Digital exhibition: The Kitchen in the Cabinet: Histories of Food and Science, kitcheninthecabinet.com

“While working in artifactual archives for my first book,” Robles wrote in an interview when asked to reflect on this process, “I kept finding specimens and other objects that were marked by eating in odd ways: things partially consumed, prepped for dinner, or in some cases straight-up food items, like portable soup. Given how infrequently historical food survives to the present—food practically being the definition of perishable—I realized that natural history collections could serve as shadow archives of historical foodways. Visual techniques like collage, as featured in Dean's interactive image on the website's homepage, helped us remove objects from their scientific or museological context and re-insert them back into a culinary ecology.”

Visual Experiment for Thomas C. Anderson’s Chapter, “Manchineel: Power, Pain, and Knowledge in the Lesser Antilles.”

Thinking visually can also demonstrate the limits of historical attempts to uncover the “secrets of nature.” Thomas C. Anderson’s chapter in the volume centers the poisonous manchineel tree as an object that lays bare the plurality of different perspectives on nature studies that each complicate any notion of a universalizing, European view of nature. The chapter deconstructs an account of an exploitative medical experiment conducted by a French colonist to show how the Caribbean environment was a contested space in which knowledge of so-called “secrets of nature” figured at the center of a clash of worldviews between Europeans and the people they subjugated in that region. Scrutinizing and unraveling the physician’s account of his proceedings helps reveal how the terms of the experiment itself reflected colonial pretensions about the natural world and how its products might be used against Europeans who found themselves far from metropolitan centers. In correspondence about the process, Anderson notes that “visual techniques are essential to my overall inquiry, since engaging with the ambiguities, inaccuracies, and contradictions between different European depictions of the manchineel helps reveal the limits of colonial nature studies, in the process making room for an analysis that takes seriously some of the many other ways that the natural world can be interpreted, utilized, and inhabited.”

What is in a scientific image that creates a sense of importance? Does it refer to an identifiable artistic genre, a faculty of imagining, a similar kind of feeling or presumed intentions it tries to communicate with a seer who already knows what to expect? For naturalists and their artist collaborators, scientific visualizations were epistemological arguments. Many natural histories embraced naturalism, a technique of representation that claimed to match optical experience with an assumed objectivity in viewing nature. They also used images to take natural things out of their original places. Playing on this tradition of early modern naturalists, the visual experiments in Natural Things are intentionally recombinatory and reliant on digital collage to pull visual sources out of place and create new meanings via their displacement. We hope that the result is a volume that features images worth thinking with, from both the past and the present.

Mackenzie Cooley is an intellectual historian who studies the uses, abuses, and understandings of the natural world in early modern science and medicine. Her book, The Perfection of Nature: Animals, Breeding, and Race in the Renaissance (The University of Chicago Press, 2022) concerns the history of biology in Italy and the Spanish Empire. Her articles have been published in Isis: Journal of the History of Science Society, Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, and Journal of Medieval Worlds. She is Assistant Professor of History at Hamilton College.

Anna Toledano is a historian of science and a museum professional. Her academic research focuses on natural history collecting in eighteenth-century Spain and Spanish America. Material culture—ranging from pressed plants to stuffed birds to woolen fibers—is the common theme throughout her work for diverse audiences. Toledano will receive her Ph.D. in History from Stanford University in 2023.

Published: 05/08/2023