What does a Critical Data Studies look like, in 2023?* A Workshop Report

Catriona Gray09/08/2023 | Report-Backs

In early July, Cambridge Digital Humanities (CDH) convened a multidisciplined group of researchers for a one-day workshop entitled Data: Materialities, Infrastructures, Critiques. As infrastructures like cloud computing and data centres continue to expand, the organisers wagered, data’s material dimensions become more and more occluded. These occlusions proceed not only through the physical delocalisation of compute power, but in how we imagine computation as often “placeless, mute, ethereal, and unmediated.” When we forget that all data is, ultimately, produced and maintained, we inevitably overlook the unevenly destructive and exploitative material processes that allow it to exist (see Brodie, 2023). Social scientists, philosophers, and cultural theorists of all stripes were invited, then, to consider these recent transformations in how we generate, understand, and process data.

I attended the workshop to present a paper looking at how data is constructed as an object of regulation (and commodification) in EU law. I came to this topic via a persistent sense of perplexity about how it is that data come to be valorised and exchanged within circuits of capital. Sometimes data is made valuable directly as a commodity. In many instances, though, it is implicated in more complicated commodification processes. To understand data’s relation to capital, I have found, we need to first grapple with data’s ontology - what is data, and how is it different from, say, knowledge? I prepared my slides and notes, adding a bullet point stating that this work can be situated “where law and economic sociology meet Critical Data Studies.”

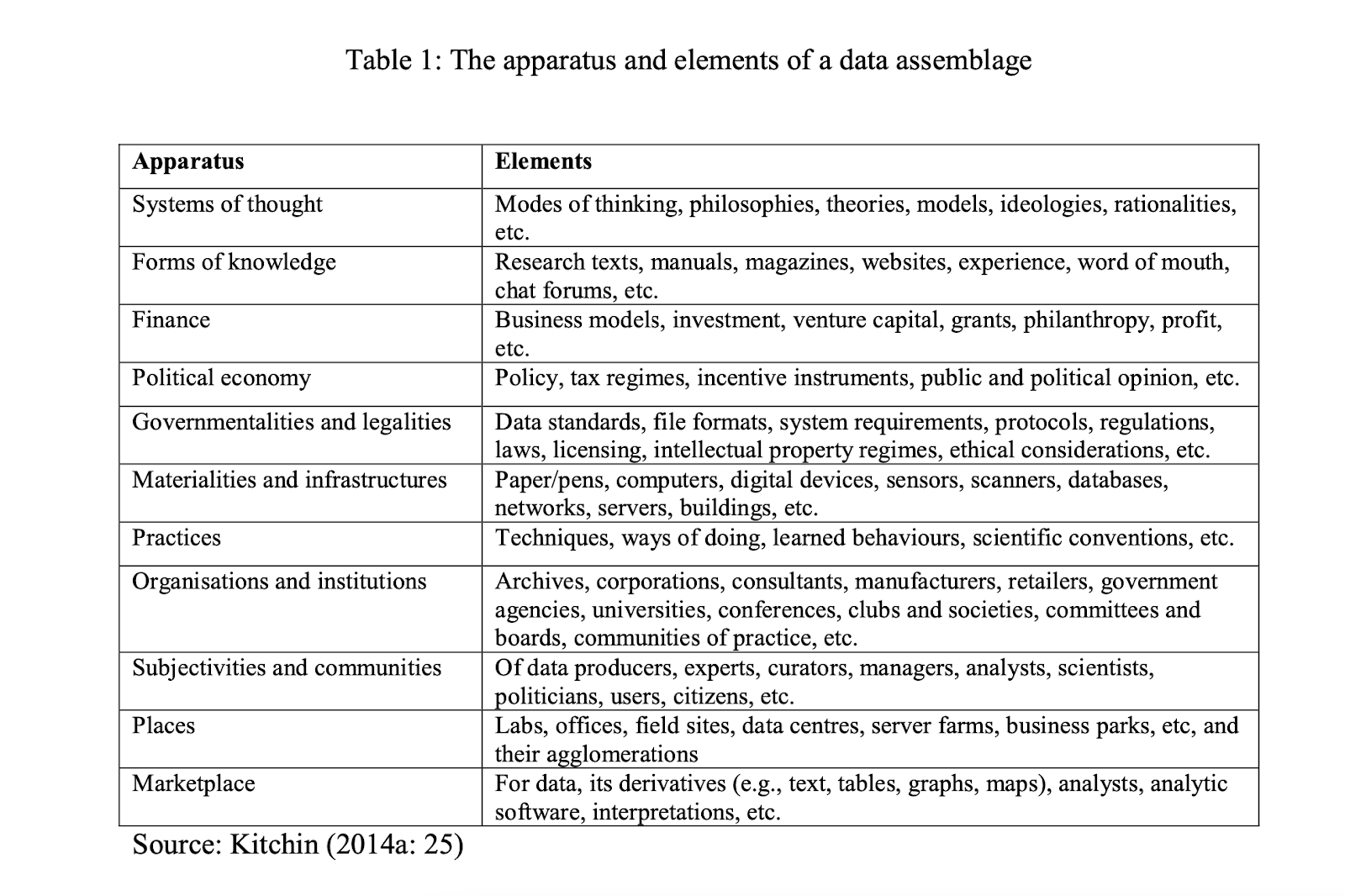

Critical Data Studies (CDS) is an interdisciplinary project that began as an attempt to systematically understand, and critique, the positivist foundations of data science. Its key thinkers apprehend data not as discrete, inert, representational entities, but as assemblages made up of various elements – among them, data’s materialities and infrastructures. The table below tells us a great deal about how data was understood within CDS in 2014. Under the apparatus “Materialities and infrastructures”, we see no mention even of the cloud – let alone any indication of the energy, minerals, and labour that lurk behind it.

Figure 1: “Table 1” from Kitchin and Lauriault (2014).

Introducing a 2016 Special Issue of Big Data and Society, Iliadis and Russo suggested that CDS has “emerged as a loose knit group of frameworks, proposals, questions, and manifestos—something to be expected of fields still in their infancy.” As I travelled up to Cambridge, I thought about what CDS looks like now it has, presumably, come of age. What would this workshop tell me about the coherence, maturity, and richness of this field in 2023?

DATA UNDERSTOOD ACROSS DISCIPLINES

The opening panel, Coloniality, Globalism and Ethnography, introduced relational analyses too often missing in dominant theoretical accounts and ethical appraisals of data and data-dependent technologies. James Muldoon, for example, showed the underlying weakness of so-called AI ethics as a framework for addressing relations of domination. Tobias Matzer presented his recent theoretical work on algorithms. His relational, situated perspective is a middle ground between research that uses algorithms as abstractions (e.g., “algorithmic culture” or “algorithmic governmentality”) and research that conceptually dissolves algorithms into empirical components, among others. Finally, delving into the social relations at stake in how we categorise and licence data, Rebecca Roberts and Stefania Merlo asked: who is open data for? The question arose out of their case study on remote, machine learning-based identification of cultural heritage sites in the Indus River Basin and surrounding regions.

Not all the talks were so directly concerned with the problematics of “data” as originally conceived within CDS. Professor Caroline Bassett’s keynote, “Anti-computing: Arendt, public happiness, and politics of thinking,” built on several of the themes of her latest open-access monograph on the history of computing dissent. While we live in an era of great anxiety around automation and data-driven technologies, this is nothing new, as Bassett contended. Her project of excavating and mapping hostility to computing over time allows us to develop alternative accounts of the computational and its impacts, and to contest the presentism characterising contemporary digital cultures. In her lecture, Bassett proposed that one such impact of computational technology is the automation of both thinking, and in some sense, following Hannah Arendt, happiness. Though more of an excursus into the affective than the material, the lecture shed light on the many registers in which dissent can emerge, and why sometimes anti-computing formations do not directly challenge power.

We then had a series of roundtable discussions, including one on government and statehood that brought together scholarship concerned, in different ways, with shifting interactions of public and private power. Nika Mahnic, for example, traced the UK’s outsourcing of government Information Communication Technology (ICT) functions and capacities to the private sector. These informational infrastructures, by freezing capacities to govern, resemble formal legislation. Management consultants contracted to improve public services are able to embed what are effectively policy choices into technical architecture. This serves to constrain policy options, create path dependencies, and leaves the state on the hook when things go wrong. A key insight from this roundtable was that data’s materialities are often accompanied by new relations of dependency and authority to govern.

Two further roundtables on Relationships, Subjectivities, Economic and Social Relationships and Aesthetics, Data Collection, Moderation and Platforms demonstrated how much data has altered our ways of living. The impressive empirical and theoretical breadth of these roundtables underlines the myriad transformations that have taken place in how we work, communicate, learn, and care. It is unsurprising, then, that the knowledge we produce as scholars would be similarly heterogenous and not without its own tensions. We identified potential disciplinary differences in, for example, the very concept of subjectivity. These tensions matter. Too often, I have found, descriptions of research as “interdisciplinary” gloss over what would otherwise be contentious, even rival, positions. If sociologists, cultural theorists, geographers, lawyers, economists, anthropologists – and the many others represented at this workshop – are to productively engage with one another, identifying our own key concepts and philosophical presuppositions seems a good place to start.

A preoccupation with the political economic recurred throughout the course of the day. In the afternoon panel on Political Economy and Legal Regulations, Jennifer Cobbe explored how digital services, including AI, are now generally distributed across highly dynamic supply chains underpinned by cloud-based data processing. Crucially, the flow of data is what holds the supply chains together across many actors positioned in unstable configurations. The interactions of these actors, through data, is constitutive of the AI technologies themselves, including their functionalities. These chains are characterised by complex interdependencies and significant power and informational asymmetries between, for example, hyper-scale cloud service providers and downstream actors with less power to bargain.

Figure 2: Data-driven supply chains and informational capitalism, Cobbe (2023).

The implications of these changes in the modes of distribution of AI products and services are huge. In many machine learning technologies, data are not simply inputs or outputs but also take on new material form as technological substrates (Star 1999) that provide the background conditions for other kinds of work and exchange. In other words, data are infrastructural. The cloud hyperscalers - companies like Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Meta - hold the infrastructural power to shape digital markets and future digital transformations.

TOWARDS A CRITIQUE OF INFRASTRUCTURAL POWER

Academic events can tell us a lot about the origins, trajectories, and outcomes of research fields. For instance, “artificial intelligence” was only ever imagined and named as a field of inquiry because of an academic workshop held at Dartmouth in 1956. To justify the expenditure, the organisers were required to submit a proposal and budget describing what they intended to do. The term “AI” is now widely seen as something of a misnomer for an already conceptually ambiguous field of knowledge and practice.

What does Data: Materialities, Infrastructures, Critiques tell us about the part, present, and future of CDS? Meeting so many people thinking about data in such variegated – even incommensurate – ways had me doubting myself. Had I been at a Critical Data Studies workshop at all? What surprised me most about this workshop was how far the contributions took us beyond the early preoccupations of CDS. I was the only contributor, for example, still placing emphasis on the ontology of data. I learned that many insights of CDS – that data are performative, not just representational; processual, not static – are now commonplaces. Clearly, we have moved on from abstract analysis of data as such, or a general critique of data science.

Like data itself, there is a “peculiar ontology” to infrastructures – at once “things and also the relation between things” (Larkin, 2013; quoted in Barney, 2018). Infrastructure embodies, materialises and reifies social relations, making them appear to be “just there, beyond the social and outside history” (Barney, 2018). Above all, the workshop brought home to me how pervasive relations of infrastructural dependence through data now are. Just as oil companies once popularised ways of living that depended on oil, bringing with them new forms of politics, we now depend on the infrastructural dimensions of data for living. I left Cambridge thinking: if our aim is to uncover such power relations – which structure and are structured by data – heterogeneity is par for the course.

NOTES

*This title refers to Craig Dalton and Jim Thatcher’s 2014 article in Society and Space: What Does A Critical Data Studies Look Like, And Why Do We Care?

Catriona Gray is a sociologist-in-training at the University of Bath, UK. Her doctoral research examines the adoption and regulation of artificial intelligence technologies. She is also an Assistant Editor at Backchannels. Her Twitter handle is @CatrionaLGray.

Published: 09/11/2023