Keywords in the Critical Medical Humanities: A Model for Research and Teaching

Melissa L. Miller07/22/24 | Report-Backs

Winifred Tate delivers lecture on Coercive Care [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

How can the humanities make visible, and help the world work against, the structural inequities in healthcare of the past and present? How can keyword fluencies aid in this endeavor? Faculty working in the medical humanities at Colby College organized a conference on March 4-6, 2024, to investigate these questions and explore how research and teaching in the liberal arts can help us navigate some of medicine’s thorniest ethical dilemmas.

Hosted by Colby’s Public Humanistic Inquiry Lab (PHIL) on the Critical Medical Humanities: Perspectives on the Intersection of Race and Medicine, the conference featured a series of interventions, including research talks, classroom takeovers, interactive workshops, and public conversations. Framing each event was a keyword–some from the recent volume Keywords for Health Humanities and others of the participants’ own devising–that connects research and teaching to the critical medical and health humanities. This multidisciplinary field considers human experiences of health, illness, and disease in relation to histories, cultures, identities, and social contexts. As the editors of Keywords argue, “the language of health and healthcare is not simply a method through which we transmit information but a knowledge-shaping instrument.” In selecting specific keywords to guide their work, Colby faculty sought to elaborate a linguistic framework capable of molding future patient health and advocacy. Joining faculty and students were Professor Sari Altschuler (Northeastern University), co-editor of the Keywords volume; Dr. Hermann Haller (MDI Biological Laboratory and Hanover Medical School); and Dr. Wendy L. Miller (Create Therapy Institute). The following keywords structured the participants’ contributions: Afterlives, Art, Coercive Care, Markets, Narrative, Poverty, Reproduction, and Withheld Care. A selection of these are discussed below.

Afterlives

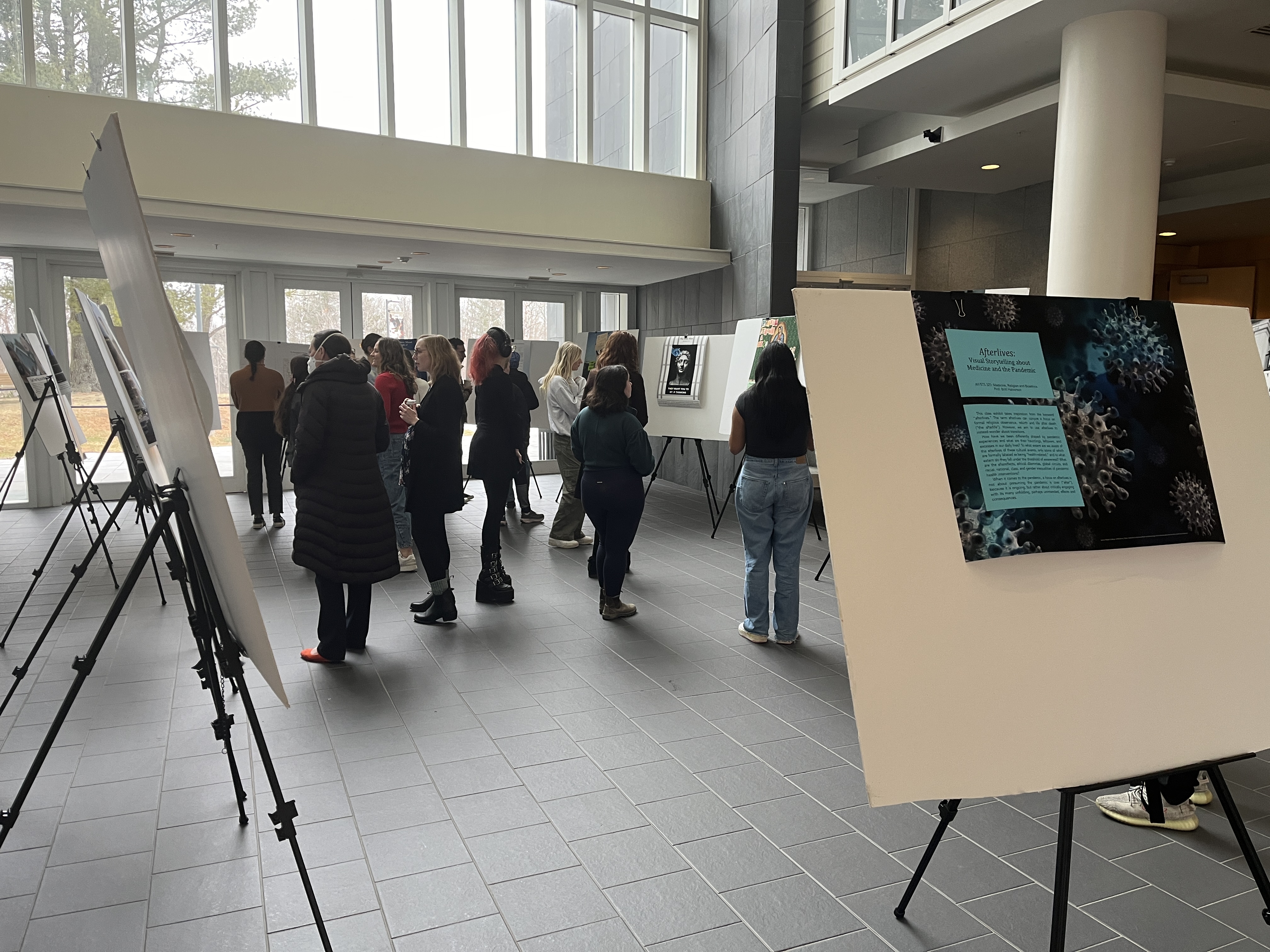

The participants in Britt Halvorson’s seminar “Medicine, Religion and Bioethics” created an exhibition that examined the afterlives of pandemic health interventions. Rather than interpret the keyword afterlives in terms of religious observance, students used it to pose broader questions about medicine and public health. For example, how have we been differently shaped by pandemic experiences and what are their hauntings, leftovers, and excesses in our daily lives? Each participant produced a visual work that drew on their own pandemic experiences, with curated text that opened up the subject for critical reflection, pulling inspiration from digital collections like Visualizing the Virus. Topics included the long-term effects of foregoing important communal rituals for death and mourning; xenophobia and virus transmission narratives; the role of medical racism in exacerbating COVID-19 health disparities among Black Americans; public discourses of autonomy and risk in debates over vaccine mandates; and chronic health conditions and medical misdiagnosis. These projects emphasized visual methods to illuminate otherwise hidden or less culturally visible aspects of medicine and public health.

Afterlives exhibition curated by Britt Halvorson's students [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

Art

How do healthcare providers use the visual arts in their daily practice? How can artists figure medical themes to aid treatment and recovery? To illuminate these questions, Tanya Sheehan engaged nephrologist and biomedical researcher Dr. Hermann Haller, expressive arts therapist and counselor Dr. Wendy L. Miller, and Assistant Professor of Art and printmaker Amanda Lilleston in conversation on how they combine art and medicine. In his medical pedagogy, Dr. Haller holds classes in art museums. During these sessions students analyze representations of illness from the point of view of the experiencer, thereby developing skills of empathy and imagination to improve the care they will provide to future patients. Dr. Miller and Lilleston each create artistic explorations of pain, such as a sculptural theater set that figures psychic trauma and prints that integrate images of human anatomy, which helps both artist and audience to heal.

As Barthman and Baruch note in the Keywords volume, creativity is “fundamental to the practice of caring for others.” In this spirit, the Oak Institute For Human Rights Student Committee, comprised of both STEM and humanities students, held a workshop at the Greene Block + Studios, a collaborative arts center in downtown Waterville, Maine. This environment granted premed students, who are typically focused on fulfilling technical requirements, the freedom to explore the creative side of the medical humanities. Collectively making personalized tote bags printed with the conference’s keywords gave participants a tangible space to reflect on how medical treatment has impacted their lives and how to apply these insights to their own ethics of patient care.

Elizabeth Jabar, Lawry Family Dean of Civic Engagement and Partnerships, helps students screen print tote bags at the Greene Block + Studios [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

Elizabeth Jabar, Lawry Family Dean of Civic Engagement and Partnerships, helps students screen print tote bags at the Greene Block + Studios [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

In her course “Drug Wars in the Americas,” Winifred Tate unpacked entangled ideas of coercive care for people who use drugs enacted in the county jail system. As part of her work with the Maine Drug Policy Lab, she shared fieldwork interviews with law enforcement, health care providers, and women incarcerated in the Aroostook County jail in Houlton and the Kennebec jail in Augusta, along with testimony and public statements about drug policy in public hearings at the Maine State Legislature. Tate revealed in her presentation how drug use is simultaneously encoded in language as a medical disease (substance use disorder) and as a crime, a choice, a moral failing, and a future risk. Jail is a place where these distinct understandings converge through the contradictory imaginings of jail as a place of care and punishment, and care as punishment. In this view, incarceration is a ‘safe’ space, where the incarcerated can gain access to health care and be forced to receive certain forms of medical treatments, and as a social safety net for a society unwilling to provide services in other forms. At the same time, incarceration is punishment, designed to impose deserved suffering on criminals, as ‘tough love’ for people who must reach ‘rock bottom’ and as a form of accountability.

Expanding her research on the Russian Medical Humanities, Melissa L. Miller discussed how comics artists in post-Soviet space use the Anglophone concept of narrative medicine–a term that does not yet exist in Russian– to advocate for better care practices in the post-USSR health landscape. By illustrating narratives of their illness, these artists use the conventions of comic illustration to critique how chronic conditions are typically portrayed. Seeking treatment from the medical establishment has trained these artists to cope with illness by dividing themselves into discrete parts, in order to deal with the pain and shame that comes from not being able to control their own bodies. Narrative medicine reveals the damage caused by this internalized subdivision, as well as offers opportunities to put one’s self together again via art and language.

On the final day of the conference, a public conversation between Sari Altschuler and Nadia El-Shaarawi highlighted the event’s groundbreaking work in bringing research and teaching in the medical humanities to a small liberal arts college. The cross-disciplinary nature of the conference’s keyword interventions, such as combining literary studies with biomedical research and employing artistic media to visualize disease, can serve as a model for students at other colleges to learn at the intersection of medicine and the humanities. As conference co-organizer Tanya Sheehan put it, “We hope that our event will inspire other colleges to define the medical and health humanities through the big ideas emerging from the research of their own faculty and students.” Sheehan and her colleagues in Colby’s PHIL welcome opportunities to collaborate with scholars and institutions seeking to develop their own engagement with this exciting and evolving field.

Author Bio

Melissa L. Miller is Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at Colby College. She specializes in the medical humanities and Russophone literature and culture from the nineteenth century to the present, with a special focus on depictions of women’s health. She is co-editor of The Russian Medical Humanities: Past and Present (2021), which brings together Russian and American scholars and health practitioners to explore questions surrounding health and healthcare, illness, and recovery in the Russian literary and cultural tradition. Her current book project examines narrative medicine and women’s health in the literature and culture of the multiethnic Russian Empire.

Editor's Comment

Ashton Wesner edited this post with assistance from Aaron Gregory.

Elizabeth Jabar, Lawry Family Dean of Civic Engagement and Partnerships, helps students screen print tote bags at the Greene Block + Studios [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

Elizabeth Jabar, Lawry Family Dean of Civic Engagement and Partnerships, helps students screen print tote bags at the Greene Block + Studios [Image credit: Tanya Sheehan]

Coercive Care

In her course “Drug Wars in the Americas,” Winifred Tate unpacked entangled ideas of coercive care for people who use drugs enacted in the county jail system. As part of her work with the Maine Drug Policy Lab, she shared fieldwork interviews with law enforcement, health care providers, and women incarcerated in the Aroostook County jail in Houlton and the Kennebec jail in Augusta, along with testimony and public statements about drug policy in public hearings at the Maine State Legislature. Tate revealed in her presentation how drug use is simultaneously encoded in language as a medical disease (substance use disorder) and as a crime, a choice, a moral failing, and a future risk. Jail is a place where these distinct understandings converge through the contradictory imaginings of jail as a place of care and punishment, and care as punishment. In this view, incarceration is a ‘safe’ space, where the incarcerated can gain access to health care and be forced to receive certain forms of medical treatments, and as a social safety net for a society unwilling to provide services in other forms. At the same time, incarceration is punishment, designed to impose deserved suffering on criminals, as ‘tough love’ for people who must reach ‘rock bottom’ and as a form of accountability.

Narrative

Expanding her research on the Russian Medical Humanities, Melissa L. Miller discussed how comics artists in post-Soviet space use the Anglophone concept of narrative medicine–a term that does not yet exist in Russian– to advocate for better care practices in the post-USSR health landscape. By illustrating narratives of their illness, these artists use the conventions of comic illustration to critique how chronic conditions are typically portrayed. Seeking treatment from the medical establishment has trained these artists to cope with illness by dividing themselves into discrete parts, in order to deal with the pain and shame that comes from not being able to control their own bodies. Narrative medicine reveals the damage caused by this internalized subdivision, as well as offers opportunities to put one’s self together again via art and language.

Withheld Care

In the context of his introduction to medical ethics course, Jay Sibara delivered a presentation that began by considering Ralph Ellison's literary representation of the protagonist's survival of biomedical violence in the novel Invisible Man (1952), which supports recent revisions by critical race feminist bioethics scholars of the dominant historiography of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Ellison illuminates the un(der)recognized role of Black women healers and family members in providing life- and health-sustaining care to Black men subjected to abusive biomedical experimentation. The presentation concluded with comparisons between the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and another longitudinal biomedical study that also controversially withheld medical treatment from research subjects: the US Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission's study of the health effects of radiation on survivors of the US atomic bombings in Japan (1947-1975).

Keyword Futures

On the final day of the conference, a public conversation between Sari Altschuler and Nadia El-Shaarawi highlighted the event’s groundbreaking work in bringing research and teaching in the medical humanities to a small liberal arts college. The cross-disciplinary nature of the conference’s keyword interventions, such as combining literary studies with biomedical research and employing artistic media to visualize disease, can serve as a model for students at other colleges to learn at the intersection of medicine and the humanities. As conference co-organizer Tanya Sheehan put it, “We hope that our event will inspire other colleges to define the medical and health humanities through the big ideas emerging from the research of their own faculty and students.” Sheehan and her colleagues in Colby’s PHIL welcome opportunities to collaborate with scholars and institutions seeking to develop their own engagement with this exciting and evolving field.

Author Bio

Melissa L. Miller is Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at Colby College. She specializes in the medical humanities and Russophone literature and culture from the nineteenth century to the present, with a special focus on depictions of women’s health. She is co-editor of The Russian Medical Humanities: Past and Present (2021), which brings together Russian and American scholars and health practitioners to explore questions surrounding health and healthcare, illness, and recovery in the Russian literary and cultural tradition. Her current book project examines narrative medicine and women’s health in the literature and culture of the multiethnic Russian Empire.

Editor's Comment

Ashton Wesner edited this post with assistance from Aaron Gregory.

Published: 07/22/2024