Interspecies Agencies: Controversies, Ontologies, and New Forms of Cohabitation (Part 1)

Gonzalo Correa and Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira03/17/2025 | Report-Backs

Editor’s Introduction

The following post introduces a multi-part, co-authored piece of scholarship, continuing Backchannels' experimental tradition in short-form communication. In a series of three posts, Gonzalo Correa and Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira will examine multispecies relations in science and technology. Part Two and Part Three will appear on March 24th and 31st, respectively.

***

For decades, scholars of science and technology studies (STS) have engaged with questions of multispecies relations, from “actor-network theory”1 and Tim Ingold’s “biosocial” anthropology2 to Donna Haraway’s theorization of “companion species.”3 These inquiries, among others, have explored various dimensions of interspecies relationships, such as labor and cooperation between humans and animals but also cross-species contagion. Building on this work, we organized a panel at the 2024 4S/EASST joint conference in Amsterdam, titled “Interspecies Agencies: Controversies, Ontologies, and New Forms of Cohabitation.” This panel aimed to bring together different papers about the role played by technoscience in shaping human and animal relationships. We were interested in how technical and material devices produce these bonds and how, in turn, vital nonhuman resistances manifest in these sociotechnical assemblages. Our goal was to gather scholarship that challenges the habitual, anthropocentric way of “thinking the animal” –a representational perspective associated with Claude Levi-Strauss4–and instead focus on imagining new ways of “living with the animal.” We sought to discuss the cohabitation of species and the production of common worlds.

Figure 1. Old Israeli military trench with a Palestinian herd in the background, near Jericho. [Image credit: Shahar Shiloach]

We organized the panel into two sessions. The first session broadly explored the production of territories through conflicts involving interspecies relations. Across all the cases presented, we saw how land–whether territory, habitat, or border–acts inseparably from the forms of life that inhabit it, functioning as a more-than-species actor, with its identity emerging from ongoing tensions. In the second session, the panelists focused on how interspecies relationships affect our methodologies. This is the first of three posts on our two-part panel. In this post, we will focus on the contributions from the first session. The second post will cover the second session. Finally, the third post will offer general reflections on the intersection of society, technology, and multispecies cohabitation.

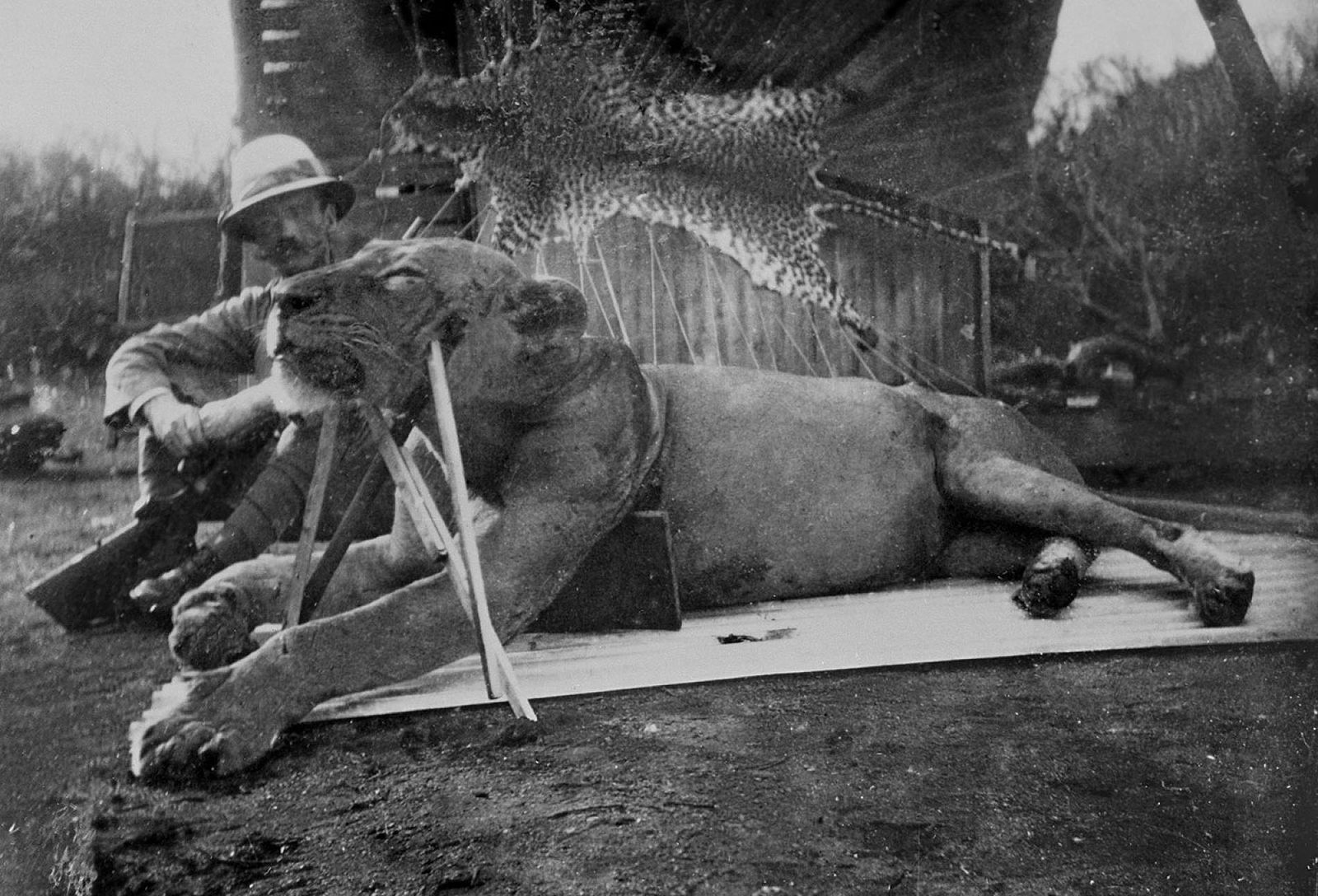

Figure 2. Colonel Patterson. [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons]

In the first session, panelists examined the socio-techno-spatial configurations that emerge through the participation of multiple species in situations of conflict. In the first paper, Wairimu Njambi and William O'Brien presented "Comrades under Siege: Insurgents, Wildlife, Terrain, and Colonial Force in Royal Aberdare National Park, 1952-1956."Between 1952 and 1956, the struggle for Kenya's independence from British rule occurred in two areas previously designated as national parks: Royal Aberdare National Park and Mt. Kenya National Park. As Wairimu and William explained, these territories were not only home to Gîkũyũ insurgents but also to various forms of life classified as wildlife. Fighters of Kenya's Land and Freedom Army used these lands as operational bases and safe zones despite the harsh geographical and climatic conditions for human survival. Their study demonstrates how the conflict deeply entangled wildlife, including water buffalo, rhinoceroses, and elephants. Due to relentless aerial bombings and military incursions by British forces, these areas—initially intended to protect nonhuman life—became spaces of vulnerability and existential risk for both wildlife and Gĩkũyũ insurgents. Wairimu and William's work highlights the unexpected forms of cooperation, tactics, and strategies that emerged between human and nonhuman lifeforms. Among these, they detail mutual aid in finding shelter and collaborative actions, such as signaling the presence of enemies through gestures. This analysis and reconstruction of multispecies participation in a war of independence expands our understanding of what constitutes allied forces.

Figure 3. Palestinian children near Israeli water and electricity lines that are not connected to their community. [Image credit: Shahar Shiloach]

In another context of ongoing and now permanent warfare, Shashar Shiloach analyzed the interactions between Palestinian shepherds and Jewish settlers in her paper "Herding in the Margins of the State: Struggle, Pastureland, and Environment in the Jordan Valley." This region is part of the occupied West Bank and lacks official national borders. Under conditions of territorial occupation by the Israeli state, Palestinian shepherding communities face the gradual reduction of their grazing lands due to pressure from Israeli settlers as well as the effects of climate change. In this space of shifting and undefined borders, local inhabitants have created a range of boundary markers composed of human and nonhuman actors. Through four years of ethnographic research based especially on images, Shahar categorizes these border markers based on their prominence, intentionality, and temporality (i.e., temporary, permanent, and seasonal boundaries). By observing and interpreting the actions of various nonhuman actors—including wind-driven trash accumulating in ravines, animal droppings, fences, vegetation, and other signs—she tells a story of political violence and resistance shaped by climate change and the weaponization of the environment. These material traces left by both human and nonhuman Palestinian actors in response to Israeli settlers reflect and reproduce the power structure of a contested colonial space.

Figure 4. Humans and non-humans using trenches, near Jericho. [Image credit: Shahar Shiloach]

Lastly, Gustavo Blanco-Wells and Pablo Iriarte's work examines a socio-techno-environmental conflict that has exposed black-necked swans to life-threatening conditions in the work "Damaged Ecologies and Unexpected Enemies: A Dramatic Tale on Black-Necked Swans, Sea Lions, and Experts in Southern Chile."5 Over the past few decades, communities around the Cruces River Estuary in southern Chile have driven a transition from intense environmental conflict to restoration processes that foster interspecies coexistence. After a pulp mill discharged wastewater and severely impacted the swan population, local communities and ecological activists recognized the black-necked swan as an emblematic species and a key symbol of their social and environmental protection efforts. This species faces a new threat nearly two decades later despite ongoing efforts to restore its habitat. However, this time, the danger does not come from the paper industry but from predation by sea lions, another protected species. In an unusual movement, a group of young male sea lions left their traditional territories, searching for new habitats and food sources and arriving at the estuary where the swans live. Riverbank residents documented and disseminated various attack incidents through social media. As Gustavo and Pablo explain, the alarm raised by local communities led to failed institutional responses, exposing the contradictory views of scientists and government experts on how to regulate interspecies coexistence within a protected and recovering ecology. Given the unprecedented nature of this new conflict, and drawing from a posthumanist perspective, they pose the following question: What possible responses emerge from interspecies controversies that unfold in complex ecologies and restorative processes?

Figure 5. Black-necked swan activism. [Image credit: Gustavo Blanco]

War was explicitly present in at least two of these cases: the Mau Mau Uprising in colonial Kenya and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the third case, war was not present in a strictly human sense even though it involved a territorial dispute between two nonhuman species, sea lions and black-necked swans, and human technicians and policymakers. In 1975, Michel Foucault inverted the maxim of the Prussian general von Clausewitz, "War is the continuation of politics by other means," asserting instead that "politics is simply war by other means."6 This inversion highlighted the agonistic dimension of politics, the struggle of forces that shape the political field. Later, Bruno Latour attributed an inherently political role to technologies, saying, "Technology is society made durable."7 Taken together, these three works teach us about the war-politics continuum in the struggle for independence, the effects on the territory of the expansive policies of the Israeli state, and an environmental conflict around habitat restoration. Technologies such as bombs and shrapnel, military waste and other debris, social networks, and environmental monitoring are part of those technologies that make conflict endure and upon which the political drifts of their resolutions are sustained.

Figure 6. The territory of research: The grazing areas of the Jordan Valley. [Image credit: Shahar Shiloach]

These technologies do not stand alone; they are surrounded by human lives and those of other animals, including elephants, goats, and sea lions–animals who also become combatants. Technological assemblages, we argue, are always biotechnological. Different forms of life, including human lives, entangle themselves in their composition, facilitating their functioning, provoking alterations, and engendering new, unexpected ways of staying together. The history of human health cannot be thought of without Pasteur's microbes or the multitude of animals that have been used in experimental tests8; the communication leap made by our satellites orbiting the Earth, a result of the space race, pays homage to the dog Laika and so many other animals.9 The howls of wolves and grunts of wild boars are part of the apocalyptic soundscape of Chernobyl.10 Interspecies encounters are part of technoscience's feats and catastrophes, both tremendous and small. An interspecies sensibility thus helps us to rethink how science and technology are made through our relationships with other species.

In the next post, we will continue exploring the participation of other forms of life in technological assemblages, this time with examples that show how researching “with” other species alters our methodologies. We will show how ethnography turns into something more when the viewpoints and vitalities of other species are incorporated into research design.

Author Bios

Gonzalo Correa (Ph.D. in Social Psychology from the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona) is a professor at the Universidad de la República in Uruguay. His research focuses on STS and multispecies studies. He is currently concluding a study on the role of cows in social composition.

Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira is a researcher and professor of the History of Psychology and STS Studies at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He has edited several History of Psychology and STS books and contributed to others, including The Routledge Companion to Actor-Network Theory and Liberalism and Technoscience. His research spans STS studies of psychological practices and STS studies of multispecies relationships.

Editor's Comment

Richard Fadok edited this post.

Footnotes

1. For example, in a now-classic actor-network theory (ANT) work, Michel Callon demonstrates the entanglement between fishermen, scientists, and scallops. See Callon, M. (1986). Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action and belief: A new sociology of knowledge? (pp. 196-223). Routledge.

2. Ingold, T. (2000). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. Routledge.

3. Haraway, D. J. (2003). The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press. See also Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

4. Lévi-Strauss C. (1949). Les structures élémentaires de la parenté. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1 vol. in-8°.

5. Blanco-Wells, G., & Iriarte, P. (2024). Ecologías Dañadas y Enemigos Inesperados: una Historia sobre Cisnes de Cuello Negro, Movimientos Sociales y Lobos Marinos en el Sur de Chile. Historia Ambiental Latinoamericana Y Caribeña (HALAC) Revista De La Solcha, 14(3), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.32991/2237-2717.2024v14i3.

6. Foucault, M. (2003). Society must be defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976 (D. Macey, Trans.). Picador. (Original work published 1997).

7. Latour, B. (1991). Technology is society made durable. In J. Law (Ed.), A sociology of monsters: Essays on power, technology and domination (pp. 103-131). Routledge.

8. Latour, B. (1988). The Pasteurization of France (A. Sheridan & J. Law, Trans.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1984).

9. Burgess, C., & Dubbs, C. (2007). Animals in space: From research rockets to the space shuttle. Springer.

10. Møller, A. P., & Mousseau, T. A. (2006). Biological consequences of Chernobyl: 20 years on. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21(4), 200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.008.

Published: 03/17/2025