Will the bubble burst? Thinking together about hype machines in the contemporary technoscience.

Ola Michalec Ph.D. (Bristol Digital Futures Institute, UK)04/21/2025 | Report Backs

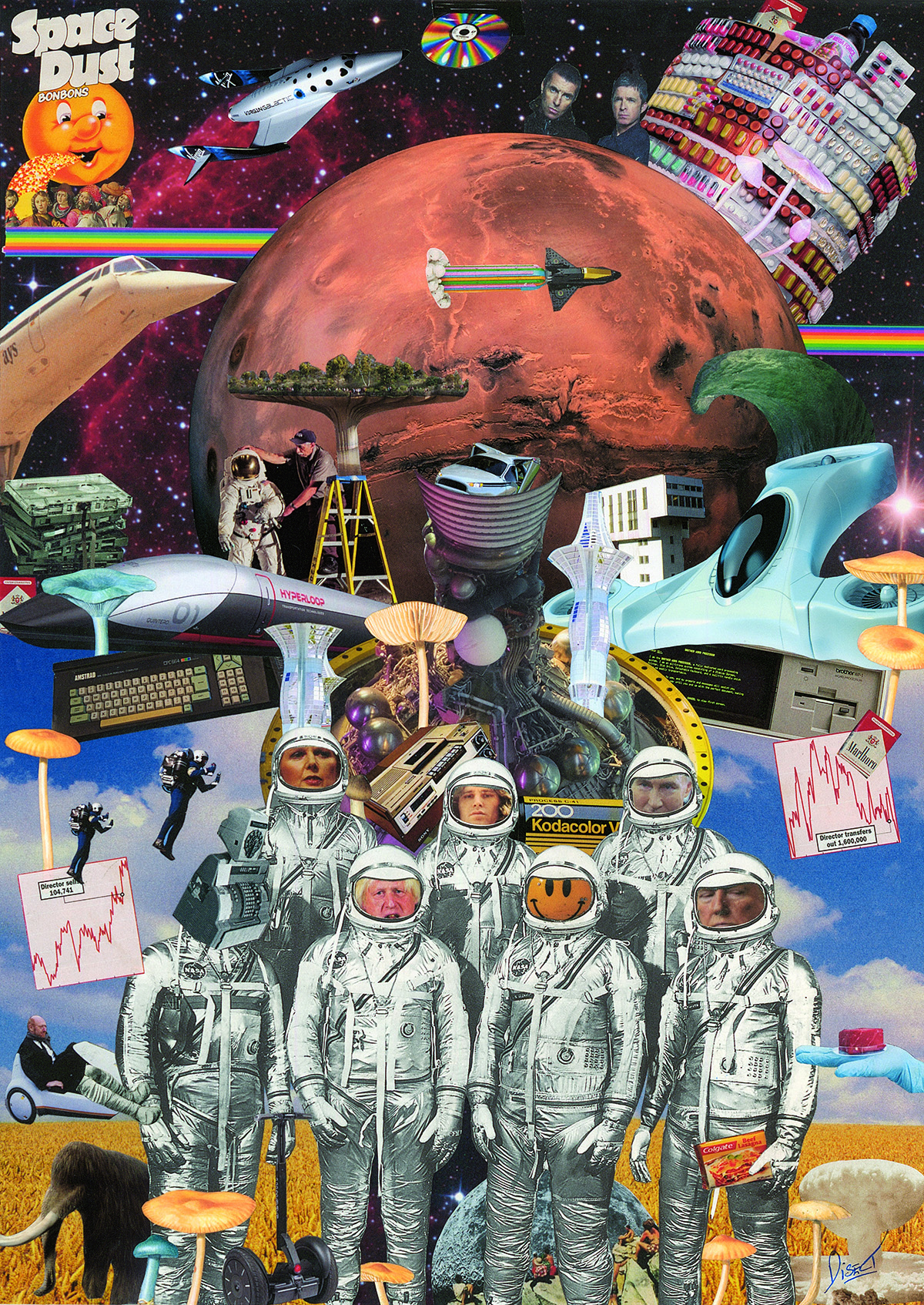

(Don’t) believe the hype by DiSect

Will the bubble burst? Thinking together about hype machines in the contemporary technoscience

The recent news cycle about Artificial Intelligence has been a perfect see-saw of excitement and disappointment. First, we’ve read about tech executives announcing prophecies that AI will revolutionise society. In the words of Jensen Huang, the CEO of NVIDIA, ‘unlike software tools designed for human use, AI can acquire skills, reason through complex problems and even collaborate with other AI systems to perform tasks autonomously’. Instead of the imaginary of the new Industrial Revolution where AI would replace millions of workers and boost economic growth, so far, we’ve predominantly seen end users experiencing the underwhelming quality of the so-called ‘AI slop’ and researchers pointing out the wide-scale theft of copyrighted materials to produce Large Language Models (LLMs). Rather than reflect on the wave of disappointment and critique, governments have been bending under the industry pressure, consulting on relaxing the copyright law to facilitate LLMs training based on artworks by musicians, writers or illustrators. Politicians across the U.S., the UK, and Hong Kong seem to have bought into this hype machine, announcing cuts to the civil service workers in the name of automation. Time will tell whether AI-powered public services will be able to process our taxes, medical records or evaluate various policy issues. For what it's worth, social scientists tend to caution against excessive hype. For example, Dr Jessica Morley, expert in AI for health data, argues: “it is crucial that this technological optimism is appropriately tempered with realism before the AI hype train carries the [UK] National Health Service to an unintended (and undesirable) destination. (...) AI development requires access to large volumes of patient data. Not only are these data often highly sensitive, but they are currently stored in hundreds of siloed databases controlled by different data controllers, in inconsistent formats, and governed by different access rules”.

Although the fast-evolving story about AI hype is certainly a fascinating one, I’m not the first one to point out how the collective excitement around innovations mobilises resources, enrols new actors, creates pressure to accelerate responses, clouds judgement, conceals power dynamics or detracts from crucial infrastructural work. ‘Sociology of expectations’ has been an active field of inquiry for over 20 years. So, can we add anything useful *now*? To clarify, I define hype as a pervasive phenomenon involving promotion, exaggerated claims, collective frenzy, leadership and strong emotional response that influences economic trends, political agendas, media narratives, and developments across technology and science.

With four panel sessions on hype (1, 2, 3, 4) during last year’s EASST/4S and several other presentations on expectations and promises (including mine), I believe that STS research on hype is in their peak, though hopefully not a peak of inflated expectations, as Gartner analysts like to put it! In this post, I would like to suggest three directions for investigating buzzwords, fads and trends related to technoscience. I will illustrate these points with examples from our recent initiative called (surprise, surprise): hype studies.

(Shapeshifting hype by Alex Wifi)

We need interdisciplinary learning

STSers are not the only ones looking at hype, with interesting contributions found across fields like innovation studies, media studies, linguistics, among many others. I would like to see more opportunities for learning from each other - a genuine exchange of ideas rather than reinventing the wheel. To use an example, let’s take the definition of buzzwords by Rose Cairns and Anna Krzywoszynska: ‘a term whose power derives from a combination of ambiguous meaning and strong normative resonance’. Hype relies on the invention of buzzwords that capture attention and mobilise diverse groups of people around them. To my understanding, the study of buzzwords has a lot in common with the study of categorisation, which is a common theme in STS research. In particular, the concept I found the most helpful was the theory of “interactive kinds” by the philosopher of science, Ian Hacking.

Using the example of the shifting boundaries of diagnoses like autism (a very hyped topic today by the way!), Hacking noticed how categories are inherently interactive. The communities of experts, those affected by categorisation, those at its thresholds, and those who claim expertise without an official recognition, engage in a open-ended, dynamic process of re-labelling, imbued with uneven power dynamics. Thinking with the works of Hacking gave me a sense of reassurance. Throughout my research career, I often found myself returning to the same critiques of digital technologies despite their constant appearance under new guises (e.g. smart cities, connected cities, and digital twins for planning representing similar ideas about implementing GIS and sensors across urban areas). This effective ‘shapeshifting’ and periodical renaming of technologies is convenient for innovators, as it helps them with evading the criticisms leveraged by STS and adjacent fields. It also facilitates launching a new round of promotional activities with each instance of renaming, therefore further sustaining the hype.

Let’s take stories, tropes and cliches seriously

Given the well-developed (even if disparate) body of knowledge considering hype, it seems to me that current research interests should turn to the generative powers of stories involving the waves of frenzy in technoscience. Technologists are typically very good at crafting the ‘foundational myths’ of their products, glossing over pivots, false starts and fiascos. The prevalence of tropes like a lone genius, a world saviour or an unsung hero leads to the proliferation of repetitive, formulaic cliches. Meanwhile, hype could be a subject of rich, longitudinal accounts, covering a wide variety of actors, emotions and outcomes. Ultimately, we need better, more honest narratives of fads so that we don’t miss out on important power dynamics or opportunities to intervene before the issues reach ‘closure’.

To be clear, ‘better’ and ‘more honest’ goes beyond the dichotomy of fabricators and fact-checkers. In fact, the themes from sci-fi, fantasy and myth studies and practice could be extremely helpful here. This is why our team has commissioned the artist called Alex Wifi to bring several hype-related ideas to life as animations. Playing with the visual tropes helped us to playfully convey the esoteric dimensions of the promises and expectations held jointly by hopeful politicians, technologists and media commentators.

(Hype machine by Alex Wifi)

Recognising the hype machine inside us

However much we might detest seeing governments announcing the coming of the AI revolutions (or, indeed, quantum revolution, nanotechnology revolution, cultured meat revolution, and many more…), both buzzwords and hype are here to stay. They are a feature of tech marketing and science, deeply entangled with the funding politics and the unknowability inherent to discovery and invention. However, there are situations which call for precision in definitions, such as the regulation of safety-critical equipment, or the accountability of government investments. In the science policy landscape so focused on testbeds and pilot projects, is it even ethical to commission R&D projects which merely demonstrate rather than deliver on a more substantive promise? Do we, as STS researchers, have the appropriate platforms and networks to call out BS when appropriate? Finally, who maintains the authority and credibility to make distinctions between what’s true and false?

While certain occasions decidedly call for a solid dose of fact-checking, in other cases, a more productive approach to hype would be a collective reflection on how STS researchers could strategically engage with buzzwords. Effective pitching of research ideas, building alliances and ‘repackaging’ our own work to different audiences are all examples of tacit knowledge. I hope that the EASST and 4S associations could become sites for the field’s self-reflexive praxis toward their own buzzwords that are both generative yet limiting. Until then, the hype machine will continue to churn out frenzied predictions, claiming the future on our behalf.

P.S. Don’t believe the hype: It’s a sequel. As an equal, can I get this through to you...

...that there is a growing movement of hype studies borne out of the EASST/4S Conference 2024. At the risk of becoming a hype (wo)man, I’d love to share that together with a group of seven other hype scholars, we have been awarded with the EASST Fund grant! This will enable us to organise our inaugural conference called ‘(Don’t) believe the hype’ in Barcelona (10-12th September, 2025 at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya; with hybrid participation available). We would like to invite scholars, artists, practitioners, journalists and curious citizens to join the conversation. The Call for contributions is open for abstracts, debates, art installations, videos and other formats until the 10th May 2025!

Bio

Dr Ola Michalec is a social scientist interested in ‘the making of’ digital innovations in the context of critical infrastructures. Currently, she is exploring the hype and reality around digital twins in the UK energy sector. She is based at Bristol Digital Futures Institute, UK.

LinkedIn || Bsky || GoogleScholar

Acknowledgements

Hype studies is a collective of several curious minds scattered around Europe: Andreu Belsunces Gonçalves, Wenzel Mehnert, Vassilis Galanos, Dani Shanley, Ola Michalec, Jascha Bareis, Pierre Depaz and Isa Luiten. Our website was designed by Pierre Depaz, the illustration was created by DiSect and the animations were made by Alex Wifi. These commissions were made possible by the grant from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council's Innovation Launchpad Network+ Researcher in Residence scheme (grant numbers EP/W037009/1, EP/X528493/1). The artwork is licenced under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Published: 04/21/2025