Around the Future Campfire: Listening with Signals and Noise

Author: Holly O’Neil (University of Technology Sydney)

Editor: Aaron Gregory (University of California, Riverside)

10/13/2025 | Reports

There’s a group of us sitting around three speakers in the upstairs gallery of the National Communication Museum in Melbourne. In this gallery space, we’re surrounded by the relics of bygone technologies; a working installation of a telephone switchboard, vintage stereos, and an array of headsets, phones and camcorders. It is fitting, sitting amongst these narratives of techno-legacy, that this is where the 2025 AusSTS conference Signals and Noise is being hosted.

The theme of this year’s inquiry invites us to think about “the problem of noise”, a corrupting, contaminating force that becomes difficult if not impossible, to untangle from its source – the signal. AusSTS invited us to consider not only how signal and noise might be separated, but how they are defined by knowledge systems that determine these categories. How might noise in fact provide productive understandings through which to “work creatively with the flotsam and jetsam of research or travel the twisting journeys of signals”?

As a visual anthropologist, I’ve joined the conference to see how these understandings of science and technology shape our storytelling and understandings of what it means to be human. As someone working in multimodal research translations, I am using the conference as an opportunity to think about how signals and noise paradigms present novel ways of thinking about climate storytelling and more-than-human ontologies, considering climate breakdown as signal or noise, and beginning to rethink power dynamics between narrative and storytelling power. I am documenting conference events through drawings, seeing the process as an opportunity to consider how to separate signals from noise.

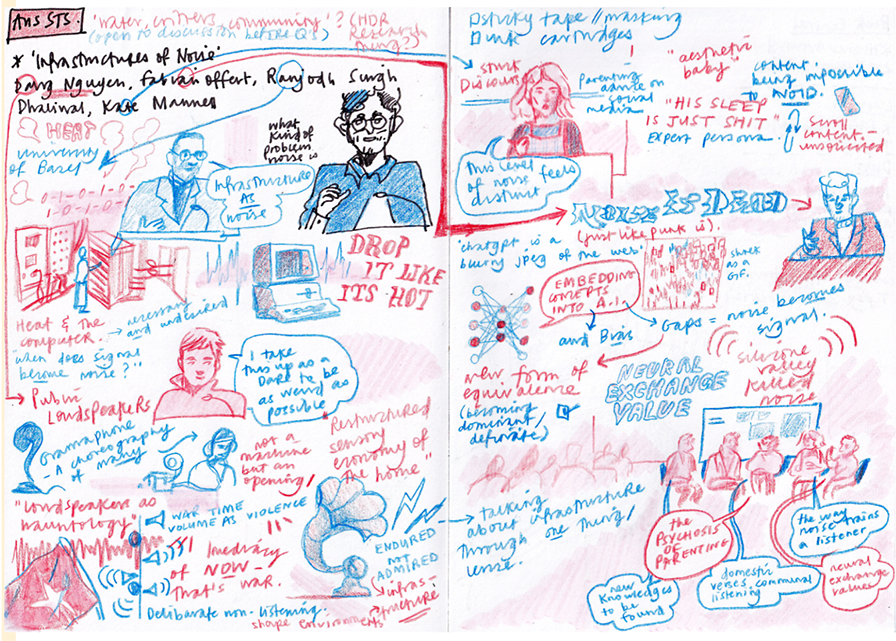

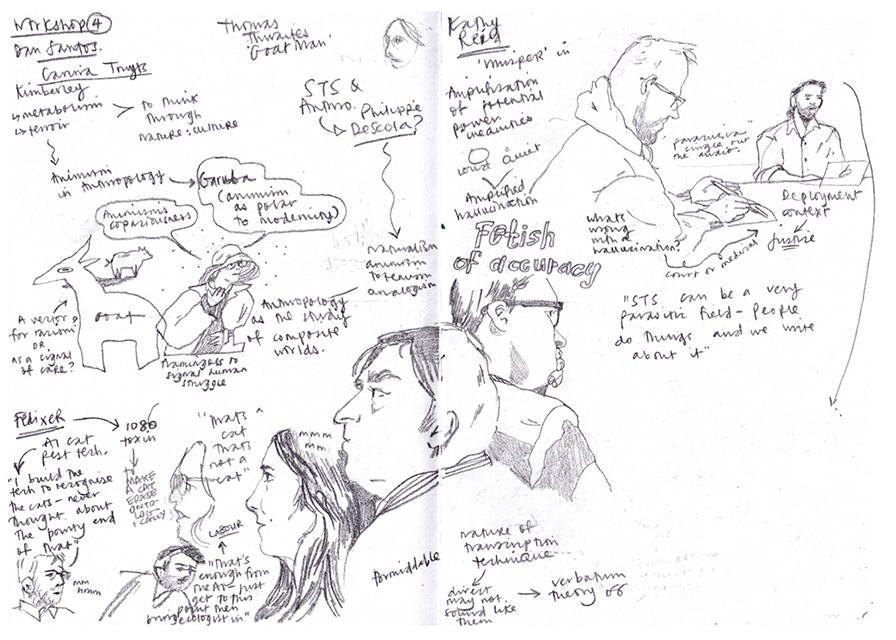

Throughout the conference, as I respond to each talk and experience them through drawing, I begin to use images and the drawing process to unpack the signals and noises of the event itself. Finding myself drawn to the interactions between humans and the muddle of modern technological discourse, I fill my pages with both images and words. In this way, drawing acts as a selective method for boiling down information, and as a bridge between the moment of creation and the future self – as a way to separate, through embodied making, signals and noise.

In the opening keynote, Infrastructures of Noise, the speakers explore the ways in which noisy infrastructure and contemporary life work side by side, asking how shifts in value impact our understandings of both noise and signal in relation to everyday human lives. Dang Nguyen follows the timeline of public:personal relationships with audio-infrastructure, beginning with a reflection on how the gramophone “restructured the sensory economy of the home” during the shift to public loudspeakers in Vietnam.

These audio infrastructures worked as agents of wartime media dissemination (“volume as violence”) prior to their contemporary uses throughout the COVID-19 pandemic as information dissemination and public control. Nguyen explores how these infrastructural cornerstones are something to be endured rather than admired, fostering a “deliberate non-listening”.

Ranjodh Singh’s exploration of heat in computing similarly proposes infrastructure as noise, opining “when does signal become noise?”, as seen in his exploration of early computing’s dealing with excess heat. This heat – noise in this context – often lead to early computational technicians wearing very little when working in control rooms, even using the heat in winter as respite from the cold. In this way, the panel explores ways that human and machine infrastructural relationships question the roles of signal and noise, often repurposing, reorganizing, and restructuring categories of uselessness and usefulness.

Back in the gallery, on the speakers around and in the centre of our circle of chairs, experimental artistic research group Machine Learning (Joel Stern, James Parker, Sean Dockray) play their new, multi-channel audio work Voyce Walkr. The piece tells the story of Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, a 1980’s sci-fi novel set in a post-nuclear holocaust future, narrated by twelve-year-old Walker. Voyce Walkr follows the story through the technological ruins of the past, creating a future imaginary in which the story is played on various devices, headsets and artefacts of the past. To create this work, Machine Learning used AI cloned speech and analogue synthesizer to manipulate the voices of the teams’ own children to consider themes of manipulation, responsibility, agency and a “scrambling of time”. The work, and the way in which we are sat listening to it, brings up images of folkloric stories around campfires – it feels like an invitation to view now as past, and enquire into futures far and near.

As children’s voices recite prose from the novel – “don’t make no difference where you start a tale”– the uncanniness of the AI puppetry, the words, tone, noise and story echo the inquiry of the AusSTS event. Human:machine dichotomies ring throughout the conference. Understandings of these relationships take hold in our explorations of signals and noise.

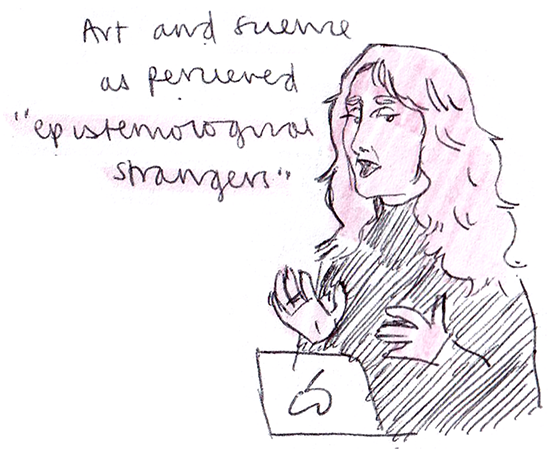

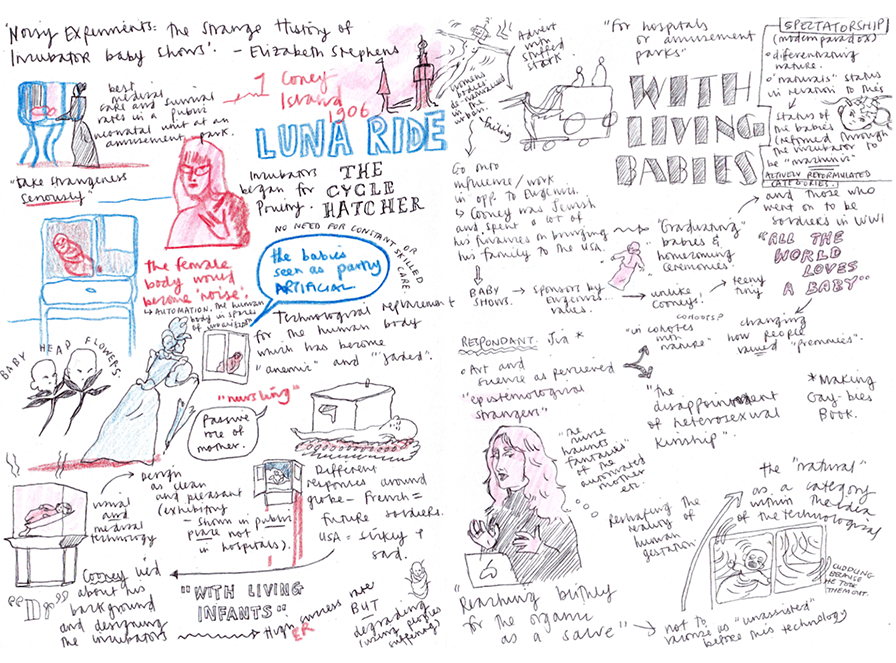

Elizabeth Stephens’ continues this thinking across these machine:human categorisations. In the keynote Noisy Experiments: the Strange History of Incubator Baby Shows, Stephens explores the role of Incubator baby shows from the 1890s until the 1940s. These incubators, often dubbed as “artificial mothers” or “automatic nurses,” sat at the intersection of science and public spectacle, exemplifying the “shifting” boundaries between human and machine. Following this keynote, Stephens and Jaya Keaney reflect on how human and machine dichotomies are too simplified, erasing histories in which humans have been assisted by technological advancements. Keaney comments that too often, when holding the human to the machine, we are “reaching blithely for the organic as a salve” rather than holding space for the inevitable overlaps we see in modern medical technologies. In this way, the presenters begin to question at what end the human body works as signal or noise – or both.

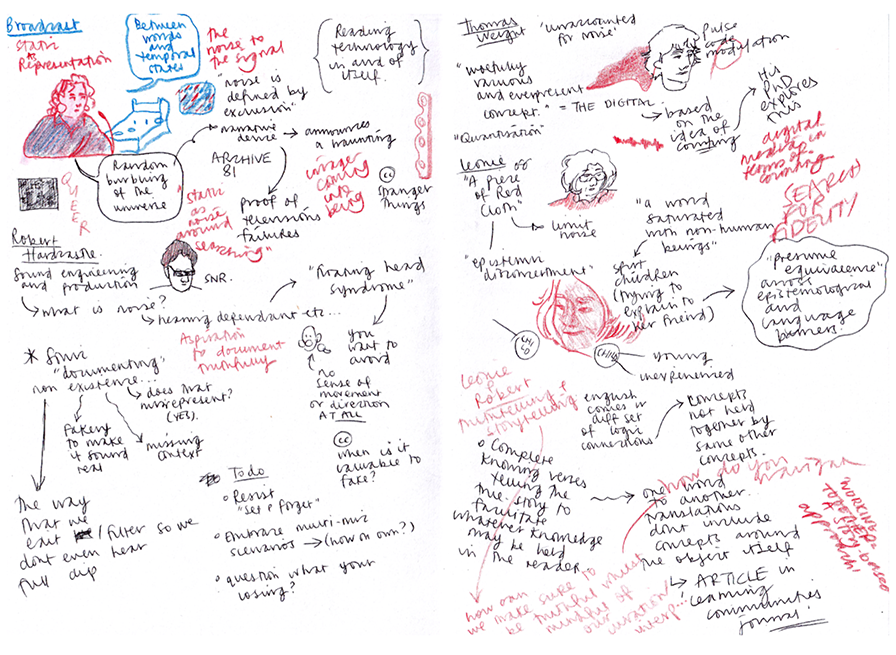

Reinterpreting noise as signal provides fruitful discourse throughout the conference, asserting a thread of insight into how queer and more-than-human enquiry might allow for a rethinking of power dynamics inherent in signal:noise, human:more-than-human, human:machine oppositions. Queerness can take hold in areas deemed as noisy. In the panel Broadcast, Kathleen Williams (University of Tasmania) addresses this dynamic in her presentation Failure to Broadcast: A media history of static. Williams explores how static (“noise, visual snow or interference”) is often co-opted in queer media, as representation and within new frameworks of understanding, shifting from an absence or noise, to a signal in and of itself. In the same panel, Leonie Norrington (CDU), Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr-Stubbs (Independent), Djawa Burarrwanga (Independent), and Djawundil Maymuru (Independent), present Working Together: A Story-based Approach. They reflect on how people come together to tell stories “across epistemic worlds”, using their narrative work A Piece of Red Cloth as a deliberate way for Yolŋu authorities to challenge and limit the noise of “mainstream Australia’s psyche and institutions that disrupt the ability for conversation, listening and understanding”. Norrington reflects on creating the book to navigate gaps and “disconcertment” between Yolŋu and English-speaking words, working with the noise of this process to “clear enough for the parties to go on together” by focusing on the turbulence of researcher dynamics in storytelling.

Working with noise is also reflected across species lines throughout the conference. In the panel Eco-acoustics, panelists explored how signals and noise across human more-than-human ontologies intersect and amplify one another. Scott Webster (University of Sydney), Kuai Shen (University of Lisbon) & Nuno Miguel’s (King Abdullah University of Science and Technology) work Songs, Silence, and Noise: Exploring Sonic Narratives of Bushfire Recovery explores how we might utilize sonic narratives to “make sense” of noise beyond human normative understandings in bushfire recovery. Similarly, Sophia Dacy-Cole’s Listening to the Noise: Soil Bioacoustics and Prosthetic Entanglement takes on the question of objectivity in beyond-human enquiry, reflecting that by listening to soil through their bio-acoustic workshops, participants might be able to shift and claim the objectivity of situated knowledges through accepting and utilizing noise.

As I pull these strings of enquiry together through the pages of my sketchbook, it becomes clear that many of these explorations are questioning and playing with noise and signals as lenses for reshaping understandings through storytelling. In the ‘Making and Doing’ sections of the events, artists and academics intercept, merge and challenge these categorizations. Anna Raupachis’ (ANU) piece Diffractive mega-constellations: creating embodied relationships with satellite imagery, works with intercepting data from an older, malfunctioning lower orbital space weather satellite. Raupachis intercepts these malfunctioning signals via radio frequency, decodes them through drawing, then re-codes them using Neural Radiance Field imaging. By following this noise to signal and back again, their work amplifies how discarded, unconsidered noise might work to represent what is often overlooked in conventional narratives of data networks. Similarly, in the workshop Surfacing Urban Water, with Alexandra Crosby, Sarah Jane Jones (UTS) and I, we explore how photodiagramming – a protocol based on ethnographic and visual communication methods – might work to separate, read, analyse, document, and share watery urban ecologies, separating them from urban noise.

Drawing can work in these contexts as a form of embodied processing, for both maker and viewer. For the maker, the hand negotiates between what is heard, how that is interpreted, and then the formation of thoughts and conceptions. No two makers will hear and interpret the same and thus drawing becomes a channel through which to create a personalised organization of signal and noise. For viewers, these images can begin to bridge gaps in understanding, interpretation, and creation. By reflecting on what is missing or present in these images, they might consider their own interpretations and takeaways – their own assumptions and considerations of signal and noise.

Furthermore, the embodied process of drawing works beyond just the moment of creation. As I sit here, rebuilding AusSTS in my mind, the drawings from those few days work as mnemonic signals to help me clarify these memories through the noise of life and the passage of time. But they also work as connections. Throughout AusSTS, fellow academics and artists alike approached me to discuss the images, reflecting on how working in this way might open paths for new ways of analysing and understanding what we had heard over the three days. We reflected and imagined through layers of technology, time and story. As in Voyce Walkr, when we sat around the proverbial campfire of the future, we began to ask: What will the legacies – or ruins – of our signals and noises say? Will they be obedient and defined? If so, who will define them? Will they distinguish signal from noise? Or will they continue to shift away from categorization, flickering in the peripheries of the fire light?

Author Bio:

Holly O'Neil is a multimodal researcher and anthro-artist. Trained in both reportage illustration and anthropology she works to combine her two disciplines in experimental and informative ways. Currently, in her PhD research, she is exploring the role of audio and visual storytelling as research methodology to engage the public with the climate crisis.

Published: 10/13/2025