The Power of Instauration: Reimagining Aesthetic Practices

Authors: Carmen Pellegrinelli, University of Trieste (Italy), Laura Lucia Parolin, Mälardalen University (Sweden), Alvise Mattozzi, Politecnico di Torino (Italy)Editor: Ludovico Rella

08/12/2025 | Report-back

The panel of STS Italian conference 2025 titled “Creating, Crafting, Designing, Fashioning, Moulding, Shaping, Fixing. Aesthetic Practices as Instaurative Practices: How to Account for Them and for the Good they Produce?” reflected on the role of artefacts within aesthetic practices. The aim was to contribute to a broader reflection about STS and “aesthetic studies”, a field of research that deals with art, works of art and, more generally, issues related to the sensory dimension.

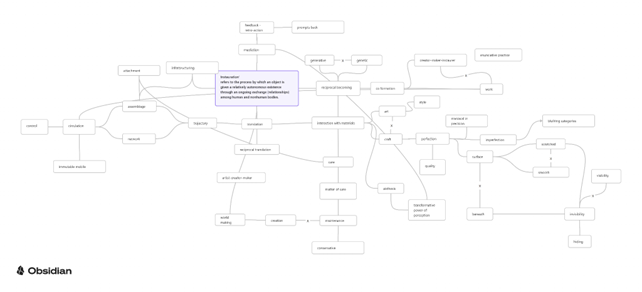

The panel invited participants to reflect on how artefacts participate in aesthetic practices. Aesthetic practices include those related to craft, design, creation, art or other work-to-be-made, which require attention to the aesthetics of the outcome in order for it to unfold all its affective potential (Mattozzi and Parolin 2021; Hennion, 2007). The key idea of the panel was to propose the concept of ‘instauration’ as a way to frame the above-mentioned practices. The term instauration - from the philosopher Etienne Souriau (1892-1979) - refers to the process by which an object is given a relatively autonomous existence through an ongoing exchange (relationships) among human and nonhuman bodies (Hennion 2013, 2016; Hennion & Monnin, 2015).

The premise of the term is that the work of art is not simply a project to be completed, but an entity that creates itself and calls for help to come into existence. The work of art (a painting, a sculpture, a music, a dance, a theatre performance) is an entity that passes from the sketch stage (ébauche, abbozzo) to completion, involving a series of human and nonhuman actors. The progression from sketch to work can be seen, according to Souriau, as an “anaphoric” process that requires constant commitment and passionate actions (Stengers & Latour 2009). Accounting for the ongoing instaurative process entails focusing on “little gestures” that allow “the gradual passage” from the work to be made, to the work as a relative autonomous entity (Souriau, 1956: 12).

Contributions to the panel developed discourse on how artefacts participate in aesthetic practices considered as instaurative. In the following, we will offer an overview of the presentations organized in four thematic sessions.

The first session of the panel focused specifically on craftsmanship, considering cases from two different fields: shipbuilding and fashion. The first case presented by Francesco Bertuccelli (University of Pisa) involved the luxury yacht construction sector. He explained how the aesthetic perfection of luxury yachts originates from an ongoing negotiation between participants regarding the translation of design into construction. The adequacy of the yacht's finishes depends on translating an initial design idea, devoid of detailed specifications, into the actual construction of the vessel.

The focus on the path from the sketch stage to the final product was also addressed by Maria Cursach (Complutense University of Madrid), in a second case about fashion. Investigating haute couture as an instaurative aesthetic practice, Cursach showed how fashion objects emerge through a continuous transformation, constantly redefined through processes of experimentation and social re-signification.

Extending the reflection, the second session of the panel focused on the field of art. ntering more specifically into a case of transformation from project to work, Aurora Donzelli (University of Bologna) analysed the artistic practice of sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro. Donzelli highlighted the relationship between the collective and impersonal dimension of art-making and the reflexive meta-aesthetic elaboration of artistic practice, also defined in relation to art market responses and critics' reviews. It emerged that the instaurative dimension of the artwork depends on a broad network that goes beyond the circumstantial moment of production.

Enrico Comes (University of Milan) invited us to broaden our gaze by adopting an ecological aesthetic perspective. For Comes, the aesthetic-ecological perspective is understood as the conceptualization of a distinctly ecological aesthetic that integrates both the technoscientific dimension of design and the creation of artifacts. By analyzing the works of artist Neri Oxman, Comes demonstrated how they embody a clear vision of harmonic “poiesis” with strong ecological and political implications.

Gianluca Burgio (Kore University of Enna) - closed the second session by entering into a practical case of ecological aesthetics,analysing the practice of dust removal within a museum context, defining it as an instaurative practice. Burgio highlighted the role of dust as a material mediator in an ongoing dialogue between humans and non-humans, revealing the hidden labor and political dimensions of care. Care emerged as a creative act that recognises the agency of matter and manifests itself as 'intra-action' (Barad, 2007) in the co-creation of the material world.

In the third thematic section, the discussion on instaurative practices shifted to topics of music and performance, and the fourth concluded with two case studies on architecture. Opening the section, Elide Sulsenti (Conservatorio G. Frescobaldi di Ferrara) described how contemporary music as a dynamic assemblage in which technical objects (such as motorised instruments) acquire agency. Her research showed how the performer becomes a co-creator in a “more than human” dialogue with technology and scores, in an instaurative process involving translation and mediation between the different participants.

The relationship between music and wine was the focus of the next contribution by Emiliano Battistini (Università di Parma) who investigated polysensory tasting as an instaurative practice. He showed how music and wine “activate” each other, generating new meanings, and giving objects (wine and music) a relatively autonomous existence. Battistini further explained how this practice offers the possibility of refining the participants' aesthetic competence, highlighting the “good” produced through co-creation. It was therefore possible to observe how, in the processes of translation and mediation involved in aesthetic practices (read under the sign of instauration), transformative dialogue occurs not only through the relationship between humans and non-humans, but also through the dialogue between different practices (like tasting and listening) that sometimes give rise to new practices, like a polysensory practice.

The fourth session closed the panel with two cases in the field of architecture. Anna Ryzhenkova (Universität Wien) presented an analysis of an architectural design process, showing how space is conceived through the ability of designing to visualize and mobilize resources while navigating different contexts. Renata Mandzhieva (Austrian Institute of Technology) analyzed a repair and maintenance project in a warehouse destined for demolition, which was used as a temporary site for a neighbourhood workshop in the city of Vienna. She explained how instaurative practices, infrastructural effects, and aesthetic practices become part of the conceptions of a 'good' (smart) city and how these are related in the experiences of those involved in the organisation and care of the project.

In summary, the panel highlighted several interesting points related to the role of objects in aesthetic practices, arising from the engagement of STS scholars with the work of Etienne Souriau and concept of instauration. To illustrate the work within the panel, we will briefly present five of these points.

The first is that it is possible to consider the work of art as something that acquires a relatively autonomous existence through a continuous exchange (relations) between human and non-human bodies.

The second is that the instauration or the emergence of the self-determining object involves network processes that are broader than the situated context of its immediate production, and that such broad networks also influence the emergence process at a distance.

The third is that instauration involves processes of translation, but above all, mediation, i.e., relations that produce surpluses, overflows, exceed and unforeseen elements born out of the conversation of the participants in the processes of poiesis.

The fourth is that in the process of instauration or co-creation of the object, all the human and nonhuman actors participating in its emergence become-with the object. It means that they enter in a process of mutual becoming.

Finally, the fifth point – the last here illustrated - is that instauration is a concept that refers not only to objects, but also to practices. Indeed, it is possible that a new practice emerges from the relationship between two or more existing ones.

Therefore, we deem that considering aesthetic practices through the key offered by Sorieau´s concept of instaurative practices can be very fruitful and should be further developed to contribute to and advance the emerging fields at the intersection of aesthetic studies and STS.

Our conceptual map of the panel discussion. Starting with the definition we provided, the discussion developed delving the definition in terms of mediation and translation, deepening on one side (the right one) the issues related to the contact and affect with a specific artifact, on the order (the left side) focusing on the circulation through translations. [Image credit: Authors]

Short bios:

Carmen Pellegrinelli is an academic working at the crossroads of social sciences and theatre. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Trieste (Italy), where she studies participatory methods in healthcare AI research. In 2023, she earned her PhD from the University of Lapland for her work on collective organisational creativity. She has published several academic articles on theatre, performance, and organisational studies, offering an original theatrical perspective on the social sciences. She is the author of “Performing Ensemble Practices, Theatre, and Social Change” (Brill, 2025), an interdisciplinary study analysing the collective practices of the Italian theatre company ATIR and their contributions to social change.

Laura Lucia Parolin is Senior Lecturer in Organization and Management at the School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University (Sweden), where she participates in the NOMP group – New Organisation and Management Practices and Transforma group – which focuses on sustainable technological, environmental and societal transformations. She works at the intersection of STS and organization studies mainly with posthumanist practice theory. Her research interests lie in the entanglement of discursive-sociomaterial practices with affects, focusing on the ethical and aesthetic dimensions of work practices and organisations. She is interested in the human and non-human contributions to responsibility, sustainability, ethics and aesthetic practices, activism, queer subjectivities and postqualitative research methods.

Alvise Mattozzi is Associate Professor of Social Studies of Science and Technology at the Politecnico di Torino, where he works in the Department of Environment, Land and Infrastructure Engineering and where he coordinates the Research Area Techno-scientific practices and socio-cultural processes. Within Politecnico di Torino he also works within the interdepartmental center FULL - Future Urban Legacy Lab and within the study center Theseus - Technology Society Humanity. His research, carried out through an Actor Network methodology, focuses on design practices, more recently tackling also the issue of interspecies design, and on controversy mapping, focusing especially on mining.

Published: 10/27/2025