Interspecies Agencies: Controversies, Ontologies, and New Forms of Cohabitation (Part 2)

Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira and Gonzalo Correa03/24/2025 | Report-Backs

Editor’s Introduction

The following post is the second in a multi-part, co-authored piece of scholarship, continuing Backchannels' experimental tradition in short-form communication. In a series of three posts, Gonzalo Correa and Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira examine multispecies relations in science and technology. Part Three will appear on 31st.

***

At the 2024 4S/EASST joint conference in Amsterdam, the panel “Interspecies Agencies: Controversies, Ontologies, and New Forms of Cohabitation” brought together papers about the role played by technoscience in shaping human and animal relationships. Our main interest was in how technical and material devices produce these bonds and how vital nonhuman agency, particularly resistance, manifests within these sociotechnical assemblages. We proposed to discuss the cohabitation of species and the production of common worlds across various scenarios.

We organized the panel into two sessions centered on distinct thematic focuses. As we highlighted in a previous post, the first session broadly explored the production of territories through conflicts arising from interspecies relations. This current post will discuss how interspecies relationships challenge and redefine our research methods, more specifically, research with other species—rather than merely about them.

In the second session, Gonzalo Correa (Universidad de la República), co-author of this post, presented "Among Cows, Humans, and Other Beings: Political Ethology as an Epistemic Assemblage." Drawing on his research into the coexistence of cows and humans in Uruguay, Correa argued that multispecies studies provide an opportunity to move beyond human-centered perspectives and rethink how we conceptualize and create our worlds. Focusing on the role of cows in shaping Uruguayan society and the state, Correa proposed an epistemological framework that he terms political ethology. This epistemic space integrates diverse traditions, including Science and Technology Studies (STS), biopolitical studies, critical animal studies, and multispecies studies. Rather than seeking to establish an autonomous disciplinary field, political ethology serves as a platform for generating new starting points in knowledge production. Historically, ethology has been characterized by the study of the social and psychological dynamics of animals in the service of understanding human behavior. Political ethology, on the contrary, draws from minority traditions of ethology to adopt a non-anthropocentric perspective that includes interspecies conflict as a central aspect of the production of worlds. Challenging the ontological divide between humanity and animality, Correa's work suggests that the social behaviors of various species reveal forms of animal politics within their existential communities. These behaviors allow us to envision non-human politics grounded not in language and reason but in affective and corporeal regimes. Notably, the distinction between human and animal politics serves not as a divider but as a bridge that enables a symmetrical understanding of the political sphere. Correa proposed that rumination as a methodology results when we allow cows’ mode of existence to affect our modes of inquiry. This involves entering into relationships, not only between individuals of different species but also between different trans-specific modes of being. The ruminative gesture permeates the ethnographic research methods as an active task of political epistemology. Rumination is, therefore, cosmopolitical, in Isabelle Stengers’ terms, insofar as it actively participates in the ontological processes that enable the unfolding of forms of life.1

In another presentation, Lisa Maria Zellner (Free University of Bolzano), Secil Ugur Yavuz (Free University of Bozen-Bolzano), Alvise Mattozzi (Politecnico di Torino), Micol Rispoli (Politecnico di Torino), Lara Giordana (Politecnico di Torino), and Elisabeth Tauber (Free University of Bolzano) explored human-fish interactions in Italian rivers. In "Dialoguing Species: Designing Common Worlds through Ethnography," they outlined preliminary findings from an ongoing research project that brings together social scientists and designers. By bridging these disciplines through STS research practices, the team aimed to develop protocols for more-than-human inclusive design. This approach sought to create technologies that enable various species to coexist in shared habitats without competition, promoting ecosystem preservation and restoration. Their multi-sited and multispecies ethnographic fieldwork investigated how fish interact with, adapt to, or resist technologies designed to support their thriving. The study combined case analyses of cutting-edge, more-than-human design projects across Europe, ranging from engineering to service design, with fieldwork conducted in two Italian contexts: a fluvial laboratory and alpine pasture livestock protection sites. The researchers analyzed the technoscientific devices engineers use to study fish behavior in northwest Italian rivers, critically examining how engineers and biologists construct fish through the methods and equipment of study and how fish, in turn, respond to or resist such interventions.

Figure 1. Ichthyologists and hydraulic engineers at work. [Image credit: Lara Giordana]

Figure 2. Telestes muticellus. [Image credit: Lara Giordana]

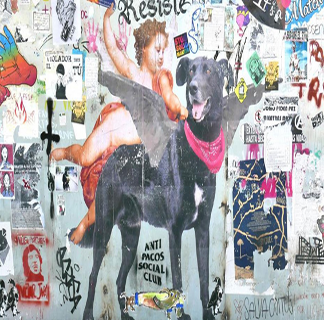

Lastly, Arthur Leal Ferreira (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro), the first author on this post, presented "What Is a Dog Able to Do? The Street Dogs (Quiltros) as Political Actors in a Post-Estallido (Uprising) Scenario in Chile." Drawing on Spinoza’s question "What are bodies able to do?", Leal Ferreira reframed this inquiry through the lenses of contemporary theorists Vinciane Despret and Donna Haraway, asking what would animals be capable of if we altered their conditions and what they would say if we posed better questions. Ferreira explored these questions through a charismatic actor in Chilean cities: street dogs, or quiltros. Using a blended ethological-ethnographic approach, he examined the co-constitution of humans and dogs in urban environments, which he described as anthropo-zoogenesis. His work reflected on this collective experience through three key concepts: 1) the emergence of a new form of citizenship that extends beyond human actors to include rights and legal considerations for animals; 2) the development of reciprocal care and domestication practices involving feeding, play, and shared occupation of public spaces, including participation in protests; and 3) the creation of a domestic cosmopolitanism characterized by relationships based on open trust and unbound by territorial or group hierarchies. Leal Ferreira argued that the presence of quiltros in Chilean cities fosters interspecies socialism, which is particularly evident during political upheavals like the 2019 popular uprising. The active role of quiltros in shared political action, especially demonstrations, underscores their significance as political actors. Leal Ferreira's ongoing research aims further to explore the post-uprising scenario, particularly developments in Chilean politics since 2021.

Figure 3. Wall in Santiago during the protests - January 2020. [Image credit: Arthur Leal Ferreira]

One of the most essential methods in STS is ethnography, which prioritizes following actors through ongoing processes of sociotechnical configuration. In this panel, multispecies relationships challenged traditional ethnographic methods. Gonzalo Correa, for instance, proposed a ruminative method with a Nietzschean basis, where the characteristic mode of existence of cows transformed ethnography and expanded its methodological boundaries beyond human politics.2 In a different vein, Arthur Leal Ferreira recast Charles Baudelaire’s flaneur through the ethological-ethnographic figure of the quiltro. Tracking and observing the movement of, and interactions between, dogs through the city used urban drift to bridge the ethological and ethnographic. Finally, in the DSooE group’s paper, the design and mode of ethnographic research were altered and shaped by the immanent relationship between the fish and the flow of water. In their proposal, ethnography became a device for multispecies dialogue aimed at designing common worlds; however, this dialogue was not logocentric but experimental (though not in the sense of traditional techno-scientific experiments). The fish's recalcitrance in response to the engineers' experimental demands was understood as an opening to different possibilities for the fish to act and participate in the knowledge production process. In this way, ethnography became a meeting ground, a kind of diplomatic artifact for facilitating dialogue between species.

Figure 4. Quiltro at a bus stop in Santiago. [Image credit: Arthur Leal Ferreira]

As in the works presented in the first post, the environment did not function as a simple passive scenario or locus of action in these papers. Across all the cases, we saw how land–whether territory, habitat, or border–acts inseparably from the forms of life that inhabit it, operating as a more-than-species actor, with its identity emerging from interspecies relationships. Cities in Chile, the Uruguayan countryside, and rivers in Italy are redefined by their interspecies relationships. These places act to redefine new citizenships, species, and even humanities and nations. The very notion of the field is redefined when the territory of ethnography becomes a key actor that transforms itself through interactions with others. Thus, fieldwork becomes intertwined with the activities of the field and what it provokes in us, making territoriality a key dimension of these more-than-ethnographic exercises.

In Part Three, the next and final post, we will offer our concluding reflections about the panel, including a discussion of the intersection of society, technology, and multi-species cohabitation.

Author Bios

Arthur Arruda Leal Ferreira is a researcher and professor of the History of Psychology and STS Studies at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He has edited several History of Psychology and STS books and contributed to others, including The Routledge Companion to Actor-Network Theory and Liberalism and Technoscience. His research spans STS studies of psychological practices and STS studies of multispecies relationships.

Gonzalo Correa (Ph.D. in Social Psychology from the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona) is a professor at the Universidad de la República in Uruguay. His research focuses on STS and multispecies studies. He is currently concluding a study on the role of cows in social composition.

Editor's Comment

Richard Fadok edited this post.

Footnotes

1. Stengers, I. (2005). The cosmopolitical proposal. In B. Latour & P. Weibel (Eds.), Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy (pp. 994-1003). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

2. For Nietzsche, rumination is a mode of thought that the modern human animal has forgotten: “One thing is necessary above all if one is to practice reading as an art in this way, something that has been unlearned most thoroughly nowadays […] something for which one has almost to be a cow and in any case not a ‘modern man’: rumination.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Preface to On the Genealogy of Morals, 1887) Nietzsche, F. (1994). On the genealogy of morality (K. Ansell-Pearson, Ed.; C. Diethe, Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.9.

3. Politics is present here not only in the aspect of composition but also of conflict, such as in the case of the Chilean violent uprising and in the diverse controversies in the countryside.

Published: 03/24/2025