Sex, Gender, and Hybrid Primate Worlds

Lilith Frakes

02/16/2026 | Report-Backs

This post is the fourth in a four-part series on “Sex and Gender in Primate Worlds,” following up on a panel of the same name at the 4S 2025 convening in Seattle, Washington, held on September 6th, 2025. This post reflects on a conference paper, “Toward a Hybrid Primatology: Purity and Knowledge in the Anthropocene."

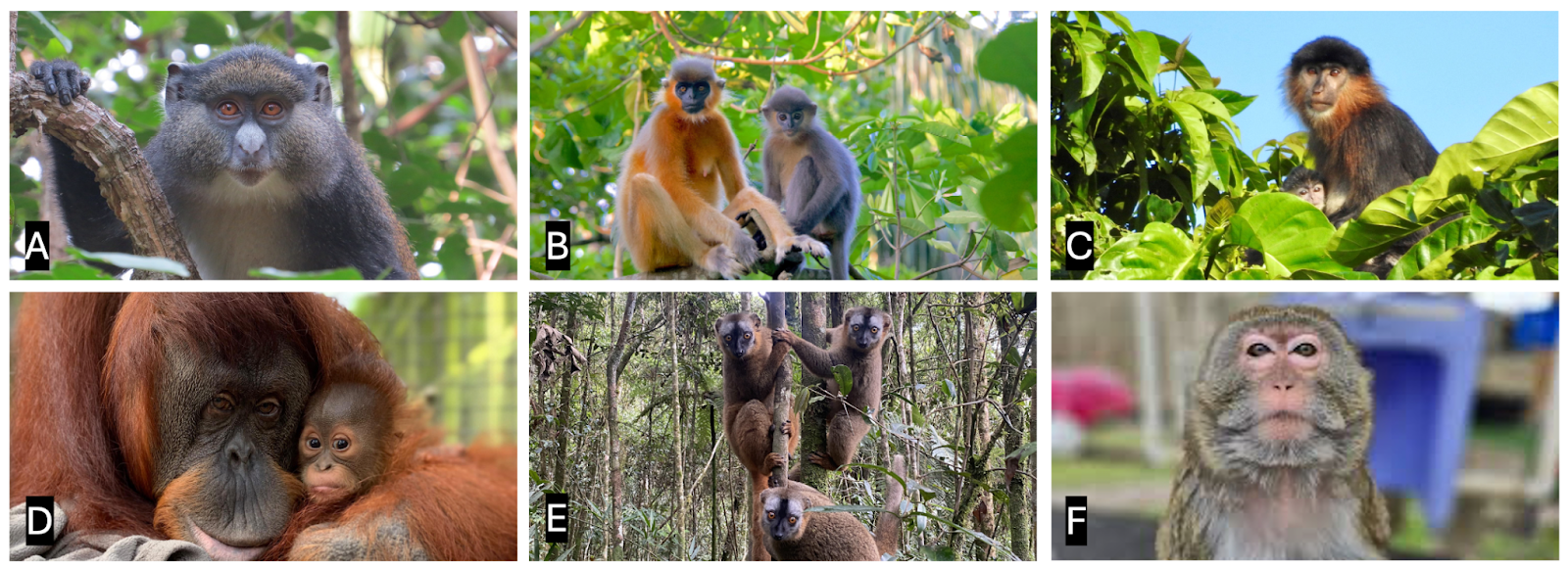

Fig. 1 Hybrid primates, whose lives cross lines of species purity as they grapple with ecological and anthropogenic change. These selected examples demonstrate a range of hybridization in non-human primates, occurring in both wild and managed captive settings, across genera, clades, and continents. (Sources for images of hybrid primates: A. A hybrid guenon monkey. B. A female capped langur and her hybrid offspring. C. A putative intergeneric hybrid in Borneo. D. A hybrid, sanctuary-housed orangutan with her daughter. E. A group of red-fronted brown lemurs--which recent genomic analyses suggest may have hybrid ancestry. F. A hybrid macaque monkey.)

Hybrid Researchers, Hybrid Questions

What does it mean to be a primatologist?

A week before the “Sex and Gender in Primate Worlds” panel at 4S Seattle 2025, panelists and organizers met online to introduce ourselves. It quickly became clear that we had arrived at primates (and at questions of sex and gender) through markedly different disciplinary routes, including history, primatology, animal research, and cultural and medical anthropology. Yet it was precisely this diversity that made the panel possible: addressing its questions required crossing scholarly boundaries and mobilizing tools from multiple fields.

Frameworks, Boundaries, and the Work of Hybridity

My own contribution to the panel, “Hybrid Primatology: Purity and Knowledge in the Anthropocene,” centered on my ongoing dissertation project, which examines the rise of hybrid primates in our current ecological moment. Hybrids are crosses between two distinct species, and have long been recognized as important in the study of evolution, particularly because hybridization can increase genetic variation and introduce traits that enhance adaptability to disease and environmental stress. However, as they challenge long-standing scientific commitments to the stability of species, hybrid primates have often ‘fallen out’ of data sets. Over the past 20 years, reports of hybrid primates have proliferated across scientific journals, citing shifting ecological conditions driven by anthropogenic change, which have brought different species into closer proximity and led to hybridization. Some of these hybrids have been declared "unnatural" as a result of human involvement in their existence. Such designations have tangible impacts: hybrids may be denied care in captivity, left out of conservation planning in the wild, and omitted from biological surveys.

Conservation policies often target the species level, imagining viable reproductive futures for threatened populations. These decisions are never purely biological; they reflect culturally grounded ideas of purity, established categories, and idealized notions of wildness. Tracing these assumptions reveals how concerns about species purity carry gendered, sexualized, and also racialized premises. Hybrids, in failing to align neatly with such preconceptions, draw attention to the ways scientific categories and conservation agendas are shaped not only by biological concerns and ecological changes but also by human imaginaries. Hybridity is a nexus at which questions of scientific authority, care practices, and conservation priorities converge and conflict.

Grappling With Purity, Sex, and Scientific Expectations

At the 4S conference, presentations revealed how deeply normative ideas about sexed and gendered behavior structure primatological research, even in domains not explicitly framed as “about” sex or gender. In my own research, I have found that hybrid primates often appear in the scientific literature as oddities, genetic dead ends, or threats to conservation – figures that deviate from assumptions about proper mating behavior, reproductive success, and “natural” family forms.

Purportedly descriptive tropes are gendered too: dominant males, compliant females, stable pairings. Hybrids violate both species boundaries and assumptions about “normal” primate reproduction (and maybe the “normal” primate order as a whole). As such, they deviate both sexually and genetically from expectations of purity. Panel conversations underscored how norms quietly shape taxonomic decisions, conservation priorities, and the narratives scientists construct about primate life.

These conversations clarified that hybrids are not peripheral to debates about sex and gender, but expose the normative scaffolding of primatology itself. Hybridity offers a vantage point for examining how knowledge is produced in primate science: how animals become legible to researchers, how certain bodies are stabilized as acceptable or marked as anomalous, and how ideals of purity organize the futures imagined for primate species. In this sense, the panel’s focus on sex and gender functioned not merely as a thematic link but as a conceptual bridge, illuminating how such questions structure the boundaries through which non-human primates are classified, managed, and valued.

Hybrid Primate Subjecthood

While dominant scientific frameworks often treat hybrid primates as classificatory problems at the edges of species boundaries, they are not merely deviations from parent species norms or anomalous datasets to be resolved. Hybrid primates are subjects in their own right, living, sensing, and responding within the worlds they co-constitute. In troubling taxonomic and epistemic lines, they resist incorporation into generalized, species-specific accounts of primate behavior, cognition, or biology. Their lives demand attention at the level of the individual, unsettling classificatory logics premised on statistical regularity and population-level coherence, and foregrounding the irreducibility of singular lives within scientific traditions that privilege species over subjects.

These primates adapt by creating new genetic, ecological, and social worlds that unfold alongside the humans with whom they live. Rather than biological mistakes, they are products of entangled, queer ecological relations. Yet for many researchers and local peoples, interpretive frameworks shaped by masculinity and domination continue to structure how hybrid behaviors are understood and valued. Attention to hybrid primate subjecthood, the ways these changing lives, bodies, and movements respond to and in turn reshape the care, management, and speculation they inhabit, reveals the gendered and sexed assumptions that often become naturalized within animal science.

Fig. 3 A hybrid primate in Northern Borneo forages for breakfast, co-constructing her fragmented habitat. Photo by author.

Toward a Hybrid Primatology

“Toward a Hybrid Primatology” is the core framework of my doctoral research, presented in this panel. It is a call for a new conception of primatology that can contend with the entangled forms of primate life emerging in our shared, human and non-human, ecological moment. A hybrid primatology asks what becomes possible when purity is no longer the organizing principle of scientific or conservation value. It foregrounds the lived realities of primates whose worlds are shaped by entanglement, ambiguity, and improvisation to respond to the conditions of the Anthropocene. In moving towards a hybrid primatology, I also seek to emphasize that, much like the hybrid practices of the researchers on this panel, we might recognize scientific practice as always hybrid, produced through institutions, histories, care relations, and shifting ecological conditions.

This hybrid framework does not reject conservation imperatives; it seeks to expand them. By reframing hybrid primates not as mistakes or ecological threats but as participants in evolving multispecies worlds, hybrid primatology opens space for more flexible, attentive, and ethically grounded ways of imagining primate futures. Ultimately, it is an invitation to rethink how primates are understood, how nature is defined, and how scientific practice might orient itself toward the flourishing of more-than-human lives amid the uncertainties of the Anthropocene.

Lilith Frakes (she/her) is a PhD student in History of Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she works closely with the Anthropology and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies Departments, as well as the Science and Justice Research Center, to study hybrid primates in a changing world. She previously earned an MS in Primate Behavior at Central Washington University. Feel free to contact her at: lfrakes@ucsc.edu

Edited by Bri Matusovsky

Published: 02/16/2026